You’ve seen the charts. Those jagged lines and shaded regions that look like a heart rate monitor gone haywire. It’s intimidating. Most students look at the ACT Science section and think they need to go back and re-read their high school chemistry and biology textbooks from cover to cover. They don't. Honestly, the biggest secret about this test is that it’s barely a science test at all. It’s a logic and data interpretation test wearing a lab coat. If you spend your time memorizing the Krebs cycle instead of grinding through high-quality act science practice problems, you’re basically bringing a knife to a gunfight.

Science is hard. This section isn't necessarily hard; it’s just fast.

The Reality of the 35-Minute Sprint

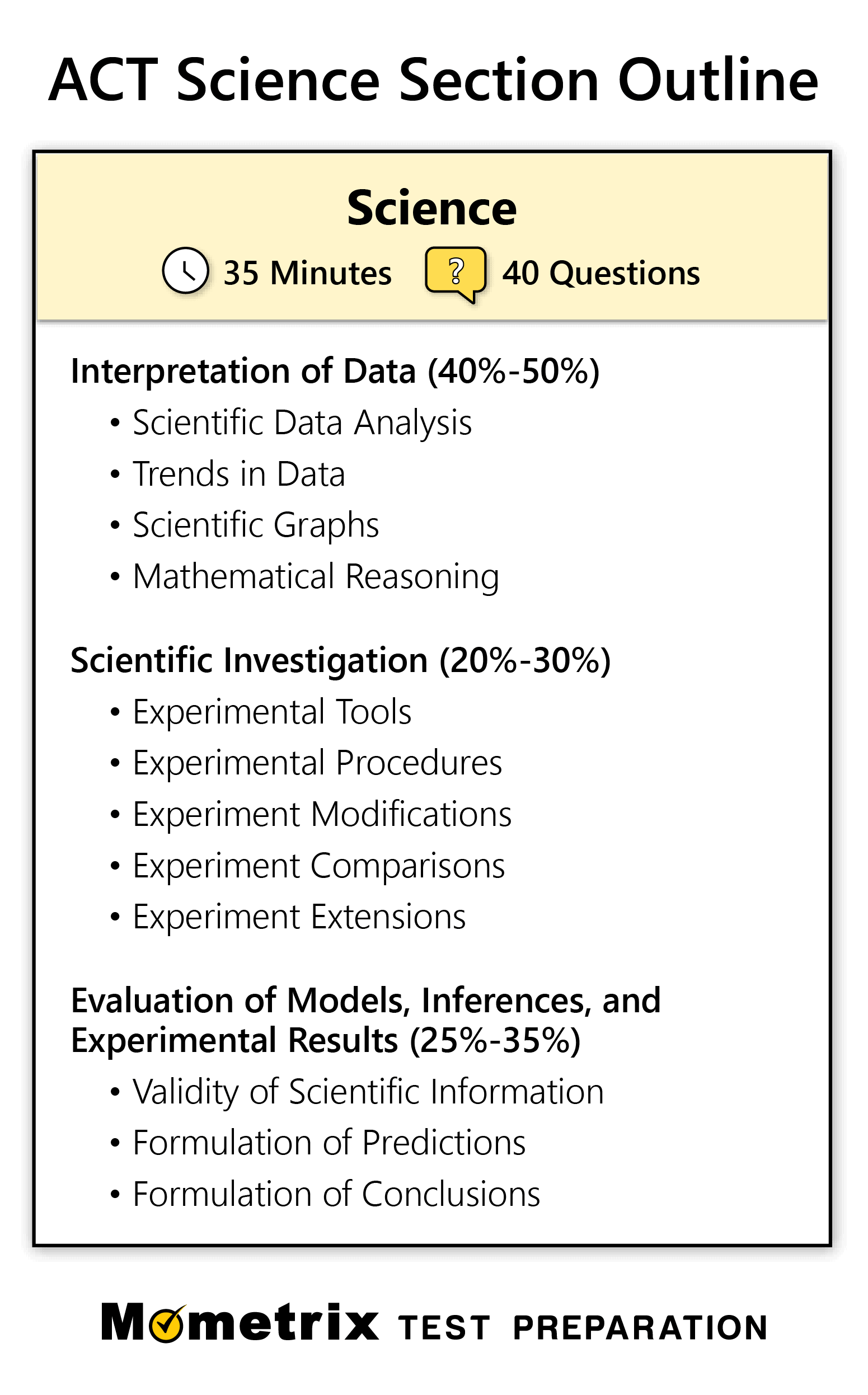

You have 35 minutes to answer 40 questions. That is less than a minute per question. It’s a frantic, breathless dash. When you start looking for act science practice problems, you’ll notice that the official material from ACT, Inc. is vastly superior to the "knock-off" versions you find in some third-party prep books. Why? Because the test has a very specific "vibe." The way they phrase questions about independent and dependent variables is incredibly consistent. If you practice with poorly written problems, you’re training your brain to recognize patterns that won't actually appear on test day.

Most people fail because they read the passages first. Big mistake. Huge.

In almost every passage—except maybe the "Conflicting Viewpoints" one where scientists argue like siblings—the answers are sitting right there in the visuals. You should be jumping straight to the questions. If a question asks about "Figure 1," your eyes should go to Figure 1. Period. Don't look at the text. Don't read the introduction about the mating habits of fruit flies. Just look at the graph. If you can find the intersection of the x-axis and the y-axis, you’ve basically won half the battle.

💡 You might also like: Why the Blue Jordan 13 Retro Still Dominates the Streets

Why Technical Knowledge Actually Gets in the Way

I’ve seen students who are literal geniuses in AP Physics struggle with this section. They overthink it. They see a question about thermodynamics and start trying to calculate enthalpy in their heads. The ACT doesn't want you to do that. They want to know if you can see that as "Temperature" goes up, "Pressure" also goes up. That’s it. It’s a direct relationship.

Spotting the "Outside Knowledge" Trap

Occasionally, the ACT throws a curveball. They might ask what a "proton" is or what "photosynthesis" produces. This is the "outside knowledge" category. According to analysis by experts like those at Prepscholar and the Princeton Review, only about 2 to 4 questions per test require actual scientific facts not found in the passage. If you’re obsessing over these, you’re missing the forest for the trees. Focus your act science practice problems sessions on navigating tables, not flashcards.

Let's talk about the three types of passages you'll encounter:

- Data Representation: These are the ones with the most graphs. They are your best friends.

- Research Summaries: These describe experiments. Look for the "Control Group." That’s the baseline. Compare everything back to the control.

- Conflicting Viewpoints: This is the "Reading" section in disguise. No graphs. Just two or three scientists or students arguing about why dinosaurs went extinct.

The Weird Art of "Guesstimating"

Calculators aren't allowed on the Science section. Let that sink in. If the math looks hard, you’re doing it wrong. If a question asks for the value at 15 seconds, and your graph only shows 10 and 20 seconds, you just look in the middle. It’s called interpolation. If you have to go outside the bounds of the graph, it’s extrapolation. Use your pencil. Physically draw the line further out on the paper. It sounds primitive, but it’s the most effective way to stay accurate under pressure.

📖 Related: Sleeping With Your Neighbor: Why It Is More Complicated Than You Think

Many students get "brain fog" around the 25-minute mark. This is where the practice pays off. You need to build the "stamina" to look at a complicated table and not blink.

Stop Treating Every Passage the Same

You don't have to do the passages in order. If you hate the Conflicting Viewpoints passages because they take too long to read, save them for last. Knock out the quick-hit Data Representation questions first. It’s about points per minute. Secure the easy wins.

There's a specific type of question that asks you to "suppose" a new experiment was conducted. These are "Extension" questions. They want to know if you understand the underlying trend. If adding 5 grams of salt increased the boiling point by 2 degrees, what happens if you add 10 grams? It probably increases by about 4 degrees. You don't need a PhD; you just need to spot the slope of the line.

Where to Find the Best Practice Materials

Don't just Google "free act science practice problems" and click the first link. A lot of that stuff is outdated junk from 2012. The test has changed. It used to have 7 passages; now it almost always has 6. That changes the timing significantly.

👉 See also: At Home French Manicure: Why Yours Looks Cheap and How to Fix It

Check out the "Official ACT Prep Guide" (often called the Red Book). It's the gold standard. Also, websites like CrackACT host older, released exams. These are actual tests that real students took in previous years. Nothing beats the real thing. When you use these, simulate the environment. Sit in a hard chair. No music. No snacks. Use a timer that counts down, not up. The psychological pressure of the ticking clock is half the difficulty.

Common Pitfalls in Data Interpretation

- Mixing up the Axes: Seriously, check twice. Is time on the bottom or the side?

- Ignoring the Key: Sometimes "Line A" is solid and "Line B" is dashed. Don't mix them up.

- Units of Measurement: If the graph is in milligrams and the question asks about grams, they are trying to trick you. They love doing that.

- Over-Reading: If the question doesn't ask you to explain why something happened, don't try to. Just find the number.

The Strategy for "Conflicting Viewpoints"

Since this passage is the outlier, it needs its own strategy. Read the first sentence of each scientist's paragraph. This usually tells you their main "thesis." Scientist 1 thinks a meteor killed the dinosaurs. Scientist 2 thinks it was volcanic eruptions. Write a tiny note in the margin: "Meteor" vs "Volcano." This prevents you from getting lost in the technical jargon that follows. When a question asks "Which scientist would agree that dust in the atmosphere caused cooling?", you can quickly scan for that specific detail.

Nuance matters here. Sometimes they agree on the "what" but disagree on the "how."

Actionable Steps for Your Next Study Session

Instead of a massive four-hour marathon, break your act science practice problems into "sprints." It’s much more effective for this specific section because the test is essentially a series of high-intensity sprints.

- The 5-Minute Drill: Take one Data Representation passage. Set a timer for 5 minutes. See if you can get all 5 or 6 questions right without rushing so much that you make "silly" mistakes. Accuracy first, then speed.

- The Graph Hunt: Take a passage and only look at the graphs for 60 seconds. Try to explain to yourself what is happening. "As X increases, Y decreases, but only until it hits 50 degrees." If you can summarize the graph without reading the text, you’re golden.

- The Error Log: This is the most boring part, but it's the most important. When you get a question wrong, don't just say "Oh, I see it now" and move on. Write down why you got it wrong. Did you misread the graph? Did you run out of time? Did you not know a specific vocabulary word? If you don't track your mistakes, you are doomed to repeat them.

- Focus on Trends: Look for words like "increase," "decrease," "direct," and "inverse." These are the bread and butter of ACT Science.

The goal isn't to become a scientist. The goal is to become a master of finding information under pressure. Treat it like a game of "Where's Waldo," but with scatter plots and pH scales. If you can stay calm and keep your eyes on the data, that 36 is a lot closer than it looks.