You’re staring at the monitor and the heart rate is sitting at 38 beats per minute. The patient looks like a sheet of paper—pale, diaphoretic, and clearly not having a good time. This is where the ACLS protocol for bradycardia stops being a flowchart in a textbook and starts being the only thing standing between your patient and a code blue. Honestly, most people think they know the steps, but under pressure, the nuance of "symptomatic" versus "stable" gets weirdly blurry.

Bradycardia is technically just a heart rate under 60. But let’s be real. If a marathon runner has a resting heart rate of 42 while they’re sleeping, you aren't grabbing the crash cart. You’re letting them sleep. The ACLS protocol for bradycardia only kicks into high gear when that slow rate starts messing with cardiac output.

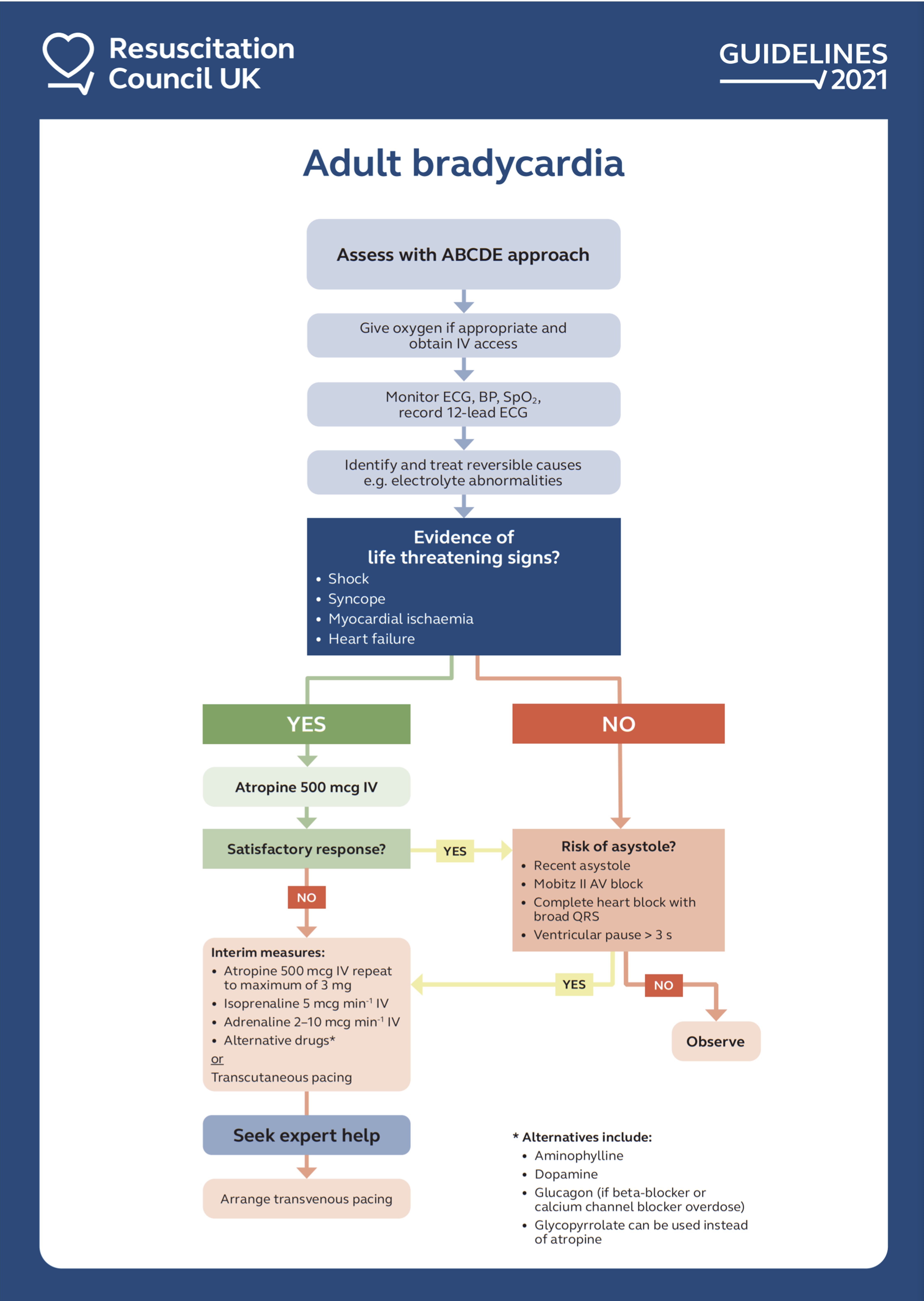

If the patient is alert, talking, and has a crisp blood pressure, you observe. You wait. You look for the "why" instead of the "how to fix it now." But once they start complaining of chest pain, showing signs of acute heart failure, or their blood pressure tanks? That’s when the clock starts.

Is the Patient Actually Unstable?

This is the billion-dollar question. The American Heart Association (AHA) defines instability pretty clearly, but in a messy ER or ICU room, it's easy to second-guess yourself. You’re looking for five specific red flags. Hypotension is the obvious one. Altered mental status is another—if they don't know what year it is and they did five minutes ago, that's a problem. Signs of shock, ischemic chest discomfort, or acute pulmonary edema round out the list.

If they have even one of these, you move. Fast.

The first thing you do isn't reaching for a needle. It’s oxygen—if they’re hypoxic. You get them on a monitor. You ensure you have IV access. You get a 12-lead EKG if it doesn't delay treatment. Why the 12-lead? Because you need to know if this bradycardia is being caused by an inferior wall MI. If it is, your management might shift slightly, especially regarding fluids and right ventricular involvement.

The First Line: Atropine’s Role and Its Limits

Atropine is the old faithful of the ACLS protocol for bradycardia. It’s a parasympatholytic, which is a fancy way of saying it blocks the vagus nerve's "braking" effect on the heart. The dose used to be different, but the current standard is 1 mg every 3 to 5 minutes, up to a total of 3 mg.

📖 Related: Why the 45 degree angle bench is the missing link for your upper chest

It works great for sinus bradycardia or first-degree blocks. It’s okay for Mobitz I (Wenckebach). But here is the thing: if you have a high-degree block like a Mobitz II or a Third-Degree Heart Block with a wide QRS complex, atropine is probably going to fail.

Actually, it might even make things worse in rare cases of high-level blocks by increasing atrial rate without improving conduction, leading to a functional "slowdown" of the ventricles. If the block is at the level of the Bundle of His or below, atropine is basically a placebo. You need to be ready to move to something more aggressive if that first dose doesn't result in a heart rate jump.

When Atropine Fails: Pacing and Pressors

If you’ve given the atropine and the monitor still shows a dismal 35 bpm, you have a choice. You can go the electrical route (Transcutaneous Pacing) or the chemical route (Inotropes).

Transcutaneous Pacing (TCP) is uncomfortable. No, scratch that—it’s painful. If the patient is conscious, you absolutely must sedate them if time permits. You’re literally sending electricity through their chest wall to force the heart to contract. You set the rate (usually around 60-80) and dial up the milliamps (mA) until you see electrical capture—a wide QRS and a T-wave after every pacer spike.

But don't stop there. You have to check for mechanical capture. Feel for a pulse. Check the blood pressure. If the monitor says 70 bpm but the patient has no pulse, you aren't "pacing"—you're just decorating the EKG strip with spikes.

The Chemical Alternatives

Sometimes TCP doesn't work well on patients with a lot of adipose tissue or those with severe barrel chests. Or maybe your pacer is acting up. This is where Dopamine or Epinephrine infusions come in.

👉 See also: The Truth Behind RFK Autism Destroys Families Claims and the Science of Neurodiversity

- Dopamine: 5 to 20 mcg/kg/min. At these "cardiac" doses, it hits the beta-1 receptors to kickstart the rate and contractility.

- Epinephrine: 2 to 10 mcg/min. This is a steady drip, not the "dead man's" 1 mg push you use in cardiac arrest.

There’s a common misconception that you must do pacing before pressors. That’s not true. The ACLS protocol for bradycardia allows you to choose based on what’s available and what’s best for the patient’s specific situation. If I have a crashing patient and the pads are already on, I’m pacing. If I have a stable-ish but deteriorating patient with a solid IV, I might start an Epi drip while I get the pacer ready just in case.

The Underlying Culprits: Searching for the "Why"

While you’re frantically trying to get the heart rate up, your brain should be cycling through the H’s and T’s. Is this a potassium issue? Hyperkalemia is a notorious cause of bradycardia that doesn't respond well to atropine. If the T-waves are peaked or the QRS is widening into a sine wave, give calcium.

What about toxins? Beta-blocker or Calcium Channel Blocker overdoses are classic. In these cases, your standard ACLS protocol for bradycardia drugs might fail miserably. You might need high-dose insulin euglycemia therapy (HIET) or glucagon.

Then there’s the heart itself. An inferior MI often causes bradycardia because the Right Coronary Artery (RCA) usually supplies the SA and AV nodes. If that artery is blocked, the "power plant" of the heart loses its blood supply. In these cases, the bradycardia is a symptom of the ischemia, and getting that patient to the cath lab is the definitive "protocol."

Specific Block Nuances You Can't Ignore

Not all "slow" is created equal.

If you see a Mobitz II, even if the patient feels "fine" right now, they are on a cliff. Mobitz II has a nasty habit of suddenly progressing to complete heart block. You should have the pacing pads on this patient even if you haven't turned the machine on yet. It’s about being proactive rather than reactive.

✨ Don't miss: Medicine Ball Set With Rack: What Your Home Gym Is Actually Missing

In a Third-Degree (Complete) Heart Block, the atria and ventricles are essentially divorced. They aren't talking. The ventricular escape rhythm is usually slow and unreliable. This is a pacing priority. Don't waste too much time on repeated doses of atropine here; it’s like trying to jumpstart a car that doesn't have a battery. You need an external power source.

Practical Steps for the Clinician

When you find yourself in the middle of a bradycardia crisis, your first move is always to assess the patient, not the screen. Screens lie. Leads fall off. Patients, however, don't lie about being syncopal.

- Check the pulse and BP immediately. If they're stable, get the 12-lead and hunt for causes like meds or electrolytes.

- Get the pads on. Even if you don't use them, having them on the chest saves 60 seconds of fumbling that you might not have later.

- Start Atropine 1 mg if symptoms are present. Max out at 3 mg.

- Transition to Pacing or Infusions if the heart doesn't respond. Don't wait until the BP is 60 systolic to decide which one to use.

- Sedate for pacing. Use midazolam or fentanyl if you have the blood pressure to support it. Pacing a conscious person without sedation is something they—and you—will never forget.

- Call for expert help. Whether that's cardiology for a temporary venous pacer or the pharmacy to help mix the Epi drip, don't be a hero.

The ACLS protocol for bradycardia is a bridge. It’s designed to keep the patient alive until you can fix the underlying problem, whether that's a permanent pacemaker, treating an overdose, or opening up a clogged artery. It requires a mix of speed and clinical judgment that only comes from knowing the "why" behind every step.

Focus on the perfusion, not just the number. A heart rate of 50 with a MAP of 70 is often better than a paced rate of 70 with a MAP of 50. Trust your assessment, follow the sequence, and always be thinking two steps ahead of the monitor.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Review your facility's crash cart: Make sure you know exactly where the pacer pads are and how to switch your specific monitor into "Pacer" mode. Every brand (Zoll, Physio-Control, Phillips) handles this slightly differently.

- Practice the "Pacing" script: Practice explaining the sensation of pacing to a conscious patient while simultaneously preparing sedation.

- Audit your recent cases: If you've had a bradycardic patient recently, check the electrolytes—specifically the potassium and magnesium levels—to see if an underlying metabolic issue was the true driver.

- Verify drug concentrations: Check if your facility uses pre-mixed Epinephrine drips or if you are expected to mix "dirty epi" in an emergency. Knowing this ahead of time prevents dosing errors.