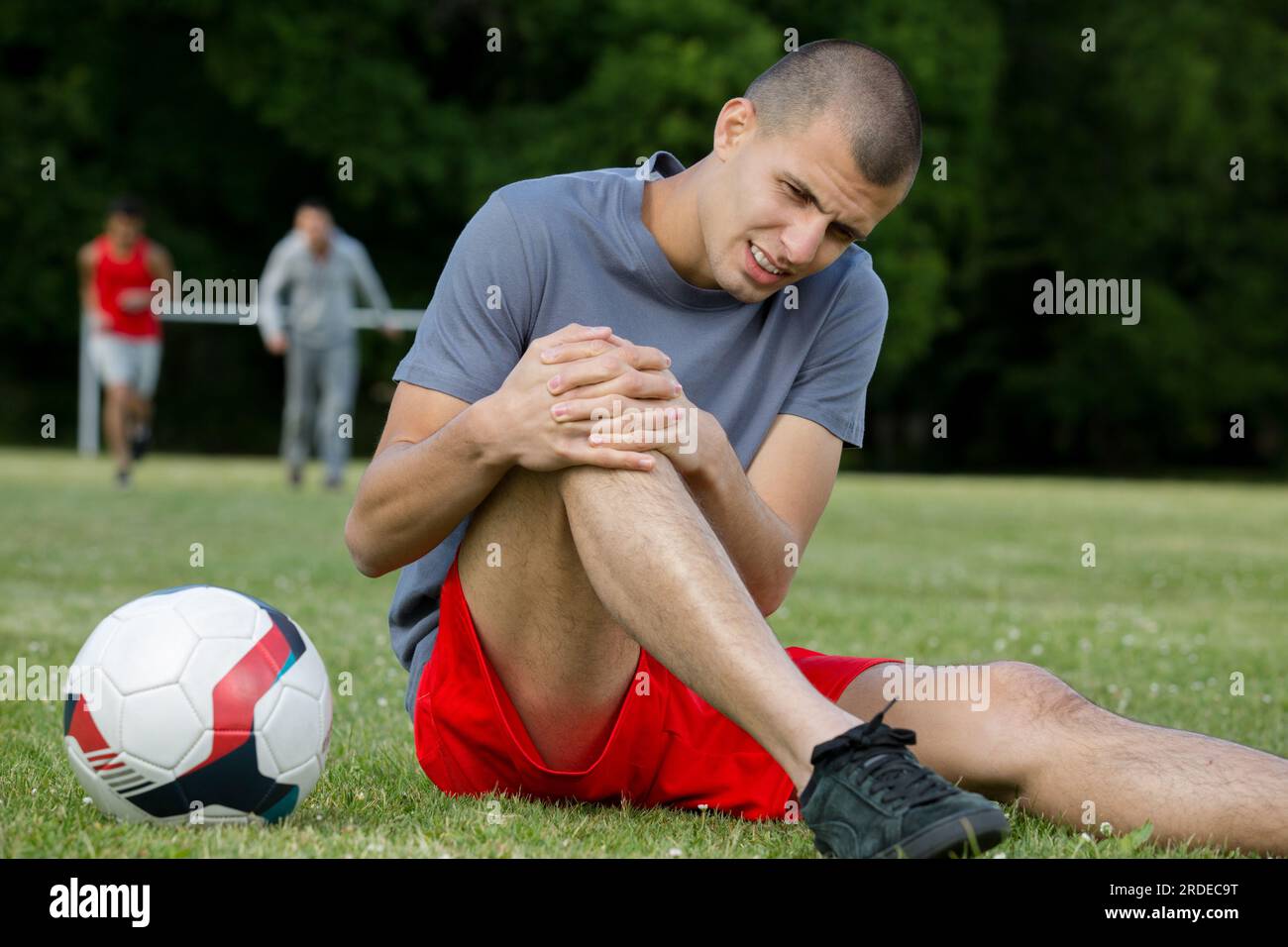

You hear the pop. Then comes the scream. If you’ve spent any time on a pitch or a gridiron, you know that sound. It is the sound of a season ending. Honestly, the ACL tear has become such a familiar injury in football and soccer that we almost expect it now. It’s a collective cringe every time a player plants their foot and their knee just... gives.

But here is the thing that really sucks. Despite millions of dollars in medical research and fancy GPS tracking vests, these injuries aren't going away. They’re actually surging in certain demographics. We keep talking about "load management" and "mechanics," yet the elite stars of the NFL and the Premier League are still dropping like flies. Why?

The Anatomy of a Familiar Injury in Football and Soccer

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) is basically a tiny rope. It’s about the size of your pinky finger. Its job is simple: keep your shin bone from sliding out in front of your thigh bone. In sports like soccer and American football, you are constantly asking that tiny rope to hold up under massive forces.

Think about a wide receiver running a post route. Or a winger in soccer trying to "cut" inside a defender. That sudden change of direction—the deceleration—is where the disaster happens. Most people think it’s the big hits that do it. Nope. Roughly 70% of ACL tears are non-contact. It’s just you, the turf, and a split second of bad physics.

Soccer players deal with a specific brand of hell because of the boots. Modern cleats are designed to bite into the grass. They provide "extreme traction." That’s great for speed, but if your studs get stuck in the sod while your body keeps turning, something has to break. Usually, it's the ACL.

In football, the issue is often the sheer explosive power of the athletes. We have 250-pound humans moving like sprinters. The torque they put on their joints is borderline unnatural. Dr. James Andrews, perhaps the most famous orthopedic surgeon in sports history, has noted for years that the specialization of young athletes is making them more brittle. They do the same movements over and over, year-round, without rest.

The Women's Game: A Different Reality

We have to talk about the discrepancy here. It’s a massive part of why this is such a familiar injury in football and soccer. Female soccer players are roughly three to six times more likely to suffer an ACL tear than their male counterparts.

✨ Don't miss: Mizzou 2024 Football Schedule: What Most People Get Wrong

Researchers like Dr. Holly Silvers-Granelli have spent decades looking into this. It’s not just "bad luck." There are physiological factors at play. Women generally have a wider pelvis, which creates a sharper angle (the Q-angle) from the hip to the knee. This puts more inward pressure on the joint. Then there’s the "intercondylar notch"—the groove in the femur where the ACL lives. In women, this notch is often narrower, essentially acting like a pair of scissors on the ligament when it’s under tension.

It’s frustrating. For a long time, the sports world just said "that’s just how it is." But now, there’s a massive push for gender-specific training. We can't train women like they’re just smaller men. Their biomechanics require different landing techniques and hip-strengthening protocols.

Turf vs. Grass: The Great Debate

If you want to start a fight in an NFL locker room, ask about artificial turf.

Players hate it. They absolutely loathe it. And the data mostly backs them up. A study published in the American Journal of Sports Medicine analyzed years of NFL data and found a significantly higher rate of non-contact lower extremity injuries on synthetic surfaces compared to natural grass.

Turf doesn't "give." When you plant your foot on real grass, a divot usually pops out. That release of soil actually saves your knee. On turf, the surface is unforgiving. All that kinetic energy has nowhere to go but back up into your leg.

- Natural Grass: Absorbs energy, breaks away under pressure.

- Synthetic Turf: High friction, stays static, forces the joint to take the brunt of the rotation.

In soccer, the "hybrid" pitches used in the Premier League—which mix real grass with synthetic fibers—are seen as a middle ground. They stay flat and fast, but they still carry that increased risk of "foot-lock." It’s a trade-off. Do you want a perfect playing surface or safer knees? Usually, the owners choose the surface.

🔗 Read more: Current Score of the Steelers Game: Why the 30-6 Texans Blowout Changed Everything

Why "Prehab" Is the New Rehab

You can't 100% prevent a familiar injury in football and soccer, but you can move the needle. This is where the "FIFA 11+" program comes in. It’s a warm-up routine designed specifically to reduce ACL injuries.

It sounds boring. It’s basically just planks, lunges, and jumping exercises. But when teams actually do it consistently, ACL injury rates drop by nearly 30-50%. The problem? Coaches get lazy. Players think they’re too elite for basic balance drills.

The focus has shifted from just getting strong to "neuromuscular control." Basically, you’re teaching your brain how to keep your knees from caving inward (valgus) when you land. If your glutes are weak, your knees take the hit. If your hamstrings are weak, the ACL has no backup.

The Mental Toll Nobody Mentions

Recovering from an ACL tear is a nine-month grind. At minimum. But even after the surgeon says the graft is "rock solid," the player's brain might not agree. This is "kinesiophobia"—the fear of re-injury.

You see it in soccer players who stop flying into tackles. You see it in running backs who stop cutting with that same violence. It takes about two years to truly get back to "pre-injury" performance levels, even if the player is back on the field in ten months. The psychological scarring is just as real as the physical one.

Misconceptions About the "Comeback"

People see Joe Burrow or Alexia Putellas come back and think, "Oh, modern medicine fixed them, they're fine."

💡 You might also like: Last Match Man City: Why Newcastle Couldn't Stop the Semenyo Surge

Not exactly.

Every time you harvest a graft—whether it’s from your patellar tendon, your hamstring, or a donor—you are changing the mechanics of that leg. There is always a "deficit." Also, once you tear one ACL, your risk of tearing the other one actually goes up. Your body starts overcompensating, putting more load on the "healthy" side until that one snaps too. It’s a vicious cycle that has ended more careers than we care to count.

Actionable Steps for Players and Coaches

If you are a coach, a parent, or a weekend warrior, you can't just cross your fingers and hope for the best. You need a strategy to mitigate this familiar injury in football and soccer.

First, stop ignoring the warm-up. If your team is just doing two laps and some static stretching, you are failing them. You need dynamic movement. Incorporate "Nordic hamstring curls"—they are painful, they are difficult, but they are arguably the single best exercise for protecting the knee.

Second, check the footwear. Stop buying the most aggressive, "bladed" cleats if you're playing on dry, hard ground or old-school turf. You want a stud pattern that allows for a little bit of rotation.

Third, prioritize "landing mechanics." Teach players to land with soft knees, never locked out. Practice jumping and landing in front of a mirror. If your knees knock together when you land, you are a walking time bomb. Fix the hip strength, and the knee will follow.

Finally, listen to the body. Fatigue is the ACL's best friend. When the muscles around the knee get tired, they stop protecting the ligament. Most injuries happen in the final fifteen minutes of a match or the fourth quarter of a game. If your form is breaking down, get off the field. It's not worth the nine-month surgery.

Focus on eccentric strength training and reactive agility drills rather than just straight-line sprinting. The goal is to build a body that can handle the "chaos" of a match, not just the drills of a practice.