St. Augustine is usually known for its Spanish forts and ghost tours. People flock to the Fountain of Youth, snapping photos of peacocks and drinking sulfur-smelling water. But there’s a different kind of history tucked away in the Lincolnville neighborhood. It’s heavy. It’s real. The ACCORD Civil Rights Museum isn’t a massive, glass-fronted institution with a gift shop selling overpriced magnets. It’s a small, unassuming building that once served as the dental office of Dr. Robert B. Hayling. If you walk by too fast, you might miss it. That would be a mistake.

Honestly, the "Oldest City" has a complicated relationship with its own timeline. For decades, the narrative was all about Ponce de León and colonial architecture. The 1964 St. Augustine movement—the one that actually pushed LBJ to sign the Civil Rights Act—was sort of pushed into the shadows. The ACCORD (Anniversary to Commemorate the Civil Rights Demonstrations) Freedom Trail and its museum changed that. It’s the first museum in Florida dedicated specifically to the local civil rights movement.

Why the ACCORD Civil Rights Museum Matters More Than You Think

Most people think the Civil Rights Act of 1964 happened because of a few big speeches in D.C. That's not the whole story. St. Augustine was the battleground that broke the filibuster. Dr. King came here. He was arrested here. But the local heroes, the ones honored in the ACCORD Civil Rights Museum, were the ones who stayed when the cameras left.

Take Dr. Robert Hayling. He’s basically the father of the movement in St. Augustine. He wasn't just a dentist; he was a leader who faced incredible violence. His home was shot into. His dog was killed. He was beaten by the KKK. When you stand inside his former office, which now houses the museum, you feel that tension. It’s not just an exhibit; it’s a site of active resistance.

The St. Augustine Four and the Cost of Courage

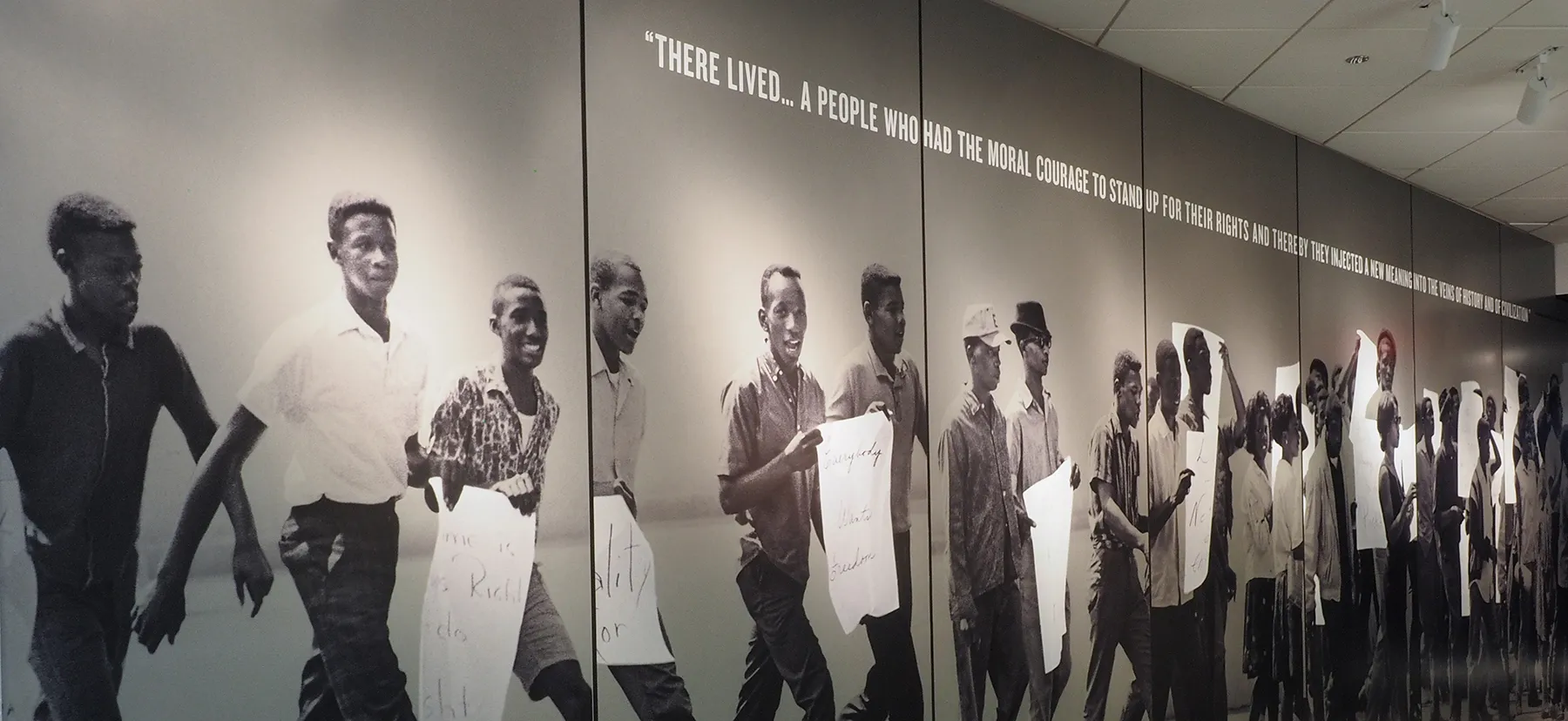

In 1963, four teenagers—JoeAnn Anderson, Audrey Nell Edwards, Willie Charles Singleton, and Samuel White—sat down at a "whites-only" Woolworth’s lunch counter. They were arrested. Most people know that part. What they don't know is that a judge told them they could go home if they promised to stop protesting. They said no.

They were sent to reform school for six months. They are known as the St. Augustine Four. The museum preserves their story because it reminds us that the movement wasn't just adults in suits. It was kids who were willing to lose their childhood for a seat at a counter.

👉 See also: Flights from San Diego to New Jersey: What Most People Get Wrong

Walking the Freedom Trail

The museum is the "anchor," but the history spills out into the streets. The ACCORD Freedom Trail consists of over 30 historic markers scattered throughout the city. You can't just sit in the museum and "get it." You have to walk.

- The Monson Motor Lodge Site: This is where the infamous photo was taken of the manager pouring acid into the swimming pool while Black and white protesters were inside. It's a Hilton now. A marker stands there to make sure nobody forgets what happened on that pavement.

- The Lincolnville Historic District: This neighborhood was founded by freed slaves after the Civil War. It’s where the meetings happened.

- St. Mary’s Missionary Baptist Church: Dr. King spoke here. You can almost hear the echoes of the "fill the jails" strategy that eventually brought the city to its knees.

The markers aren't just plaques. They are "cell phone tour" stops. You call a number, and you hear the voices of the people who were actually there. It's raw. It's better than a textbook.

The Dental Office That Changed Federal Law

The ACCORD Civil Rights Museum sits at 79 Bridge Street. It’s tiny. Maybe a few hundred square feet. But it houses artifacts that are gold for historians. We’re talking about original picket signs. Personal letters. Medical tools from Dr. Hayling’s practice.

It's weirdly intimate. You're looking at the chair where a man worked on teeth during the day and planned marches at night. It reminds you that these weren't "historical figures" in the way we see them on postage stamps. They were neighbors. They were professionals. They were scared, but they did it anyway.

Misconceptions About the St. Augustine Movement

One big myth is that the movement here was a failure because the local government remained stubbornly segregated for years after. Actually, the chaos in St. Augustine—the nightly marches through the Plaza de la Constitución where protesters were met by mobs with chains—was exactly what forced the federal government's hand.

✨ Don't miss: Woman on a Plane: What the Viral Trends and Real Travel Stats Actually Tell Us

The images of violence in this "quaint" tourist town were so jarring that they shifted public opinion nationwide. If St. Augustine hadn't been so brutal, the 1964 Act might have stalled longer. The ACCORD Civil Rights Museum does a great job of connecting these local bruises to the national victory.

A Different Kind of Experience

Don't expect the high-tech bells and whistles of the Smithsonian. This is a grassroots effort. It’s run by volunteers, many of whom are relatives of the original protesters. Sometimes, if you're lucky, you'll meet someone who actually marched.

There's no polished, corporate filter here. The displays are dense. They require you to read and think. It’s emotional. You might feel uncomfortable. That’s kind of the point. St. Augustine’s beauty is built on top of this struggle, and the museum asks you to acknowledge that debt.

What to Look For

Keep an eye out for the documentation regarding the "wade-ins." Protesters would go into the ocean at St. Augustine Beach, and the police would form lines in the water to stop them. There are photos in the museum of people being dragged out of the surf. It’s a side of Florida history that isn't in the tourism brochures.

Planning Your Visit (The Practical Stuff)

The museum isn't open 24/7. Because it's volunteer-led, you usually need to make an appointment or check their specific event calendar. This isn't a "walk-in whenever" kind of place like the Pirate Museum downtown.

🔗 Read more: Where to Actually See a Space Shuttle: Your Air and Space Museum Reality Check

- Contact them ahead of time: Visit the ACCORD website or call to ensure someone is there to let you in.

- Start at the museum, then hit the trail: Get the context at 79 Bridge Street first. Then, use the map to find the markers.

- Bring comfortable shoes: The Lincolnville area is beautiful but the sidewalks can be uneven.

- Download a QR code reader: Many of the trail markers have digital components.

The Long-Term Impact

The ACCORD Civil Rights Museum isn't just about the 60s. It’s about how a community remembers itself. For a long time, St. Augustine tried to forget. In the 80s and 90s, these stories were mostly oral histories shared in Black households.

By establishing this museum and the Freedom Trail, the city finally started to own its whole truth. It’s a work in progress. But standing in that small office on Bridge Street, you realize that the "Oldest City" is also the site of one of the newest and most vital chapters in American freedom.

Actionable Steps for Your Visit

If you're heading to St. Augustine, don't just stay on St. George Street. Head south.

- Map the Trail: Go to the ACCORD Freedom Trail website and download the PDF map. It’s a self-guided tour that you can do by car or bike.

- Visit the Plaza de la Constitución: Look for the "Andrew Young Crossing" and the Foot Soldiers Monument. These are directly linked to the museum's mission.

- Support the Museum: Since it's a non-profit, consider a donation. They are currently working on expanding their digital archives to make these records accessible to schools across the country.

- Read "If It Takes All Summer": This book by Dan Warren provides the legal and political backdrop of what was happening in St. Augustine during the time the museum commemorates.

Visiting the ACCORD Civil Rights Museum will change how you see Florida. It’s not all sunshine and theme parks. It’s grit. It’s Dr. Hayling’s dental chair. It’s four kids refusing to leave a lunch counter. It’s the history that actually changed the world.