It was Good Friday. 1865. The mood in Washington D.C. was basically electric, a weird mix of exhaustion and pure relief because the Civil War was effectively over. Robert E. Lee had surrendered at Appomattox just five days prior. People were drinking in the streets. Flags were everywhere. Then, the Abraham Lincoln date of assassination happened, and everything changed in a single heartbeat.

Honestly, it’s hard to overstate how much that one night at Ford’s Theatre derailed the entire trajectory of the United States.

The tragedy didn't just happen in a vacuum. It was a planned strike. A decapitation of the government. Most people know about John Wilkes Booth, but they forget how close the rest of the cabinet came to dying that same night. Secretary of State William Seward was stabbed repeatedly in his bed. Vice President Andrew Johnson was on the hit list too, though his assassin lost his nerve at a bar. It wasn't just a murder; it was a failed coup.

The Reality of April 14, 1865

When you look at the Abraham Lincoln date of assassination, you have to look at the timing. Lincoln was tired. He had aged decades in four years. His face in the Alexander Gardner "cracked plate" photograph from February 1865 shows a man who was literally being hollowed out by the stress of the war. He wanted to laugh. He chose a silly British comedy called Our American Cousin.

He didn't even want to go.

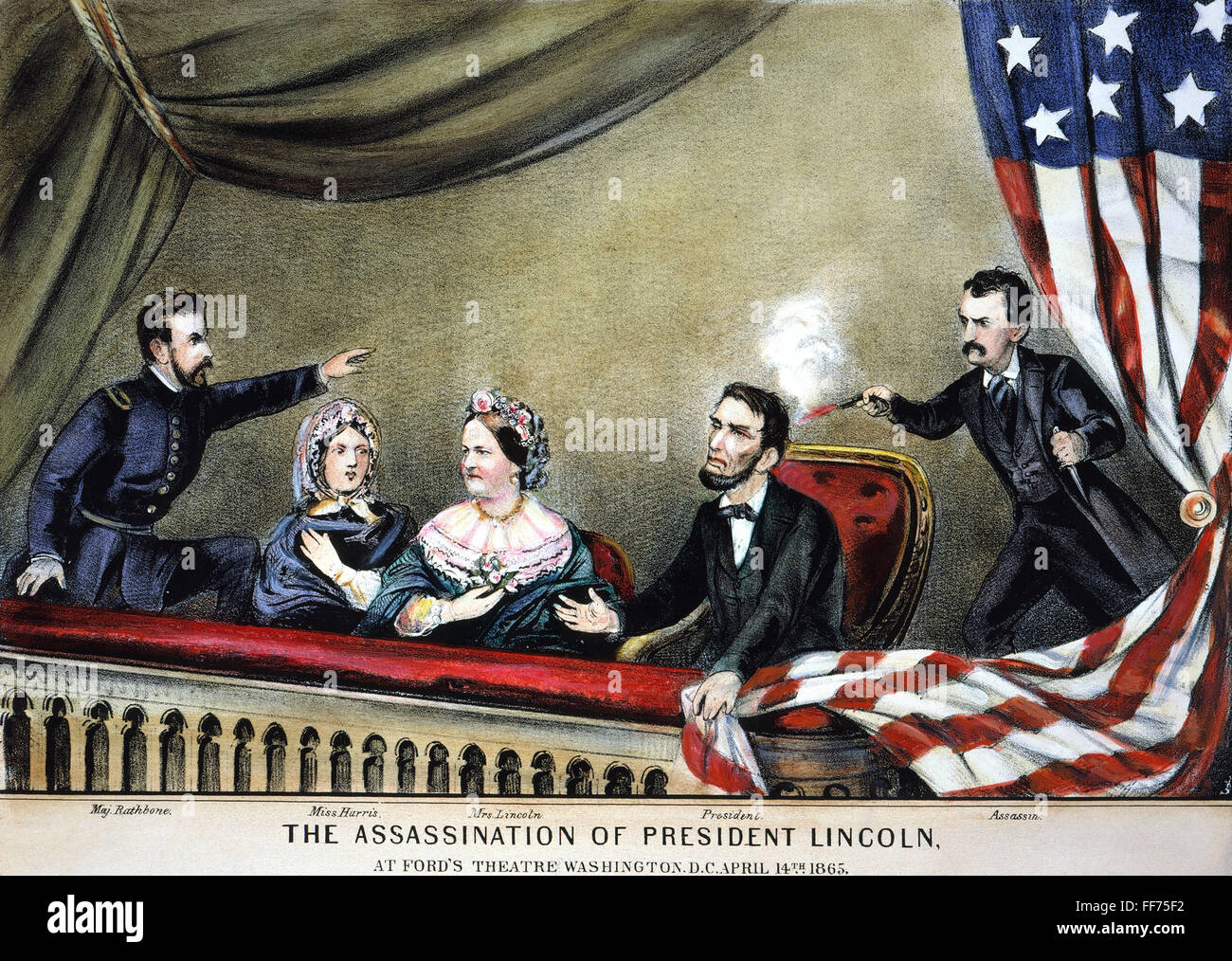

Mary Todd Lincoln later mentioned he had a headache. But the play was a benefit for the actress Laura Keene, and the President felt he couldn't let the public down. He arrived late. The orchestra stopped and played "Hail to the Chief." He sat in the State Box, which was actually two boxes with the partition removed.

Why the Security Failed

Security was a joke back then. The man assigned to guard the President’s box was John Frederick Parker. He had a terrible record. He was late. He eventually left his post to go get a drink at the Star Saloon right next door to the theater.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Air France Crash Toronto Miracle Still Changes How We Fly

Booth knew the theater inside and out. He was a famous actor, a celebrity. It would be like a Hollywood A-lister today walking into a restricted area—nobody questioned him because they recognized his face. He waited for the biggest laugh of the night. He knew the script. He knew when the line "you sockdologizing old man-trap" would bring down the house.

He stepped in. He fired a .44-caliber derringer.

The bullet entered behind Lincoln’s left ear. It was a mortal wound instantly. Major Henry Rathbone, who was a guest in the box, tried to tackle Booth, but Booth stabbed him to the bone with a large hunting knife. Then came the leap. Booth jumped from the box to the stage, about twelve feet, catching his spur on the Treasury flag. He broke his fibula. He yelled "Sic Semper Tyrannis" and vanished into the night.

The Long Night at the Petersen House

Lincoln didn't die at the theater. Doctors rushed to the box. Charles Leale, a young Army surgeon, was the first to reach him. He realized immediately that the President couldn't be moved back to the White House over the rough cobblestones. They carried him across the street to a boarding house owned by William Petersen.

It was cramped. The bed was too small for Lincoln's six-foot-four frame. They had to lay him diagonally.

The room filled with smoke, sweat, and the smell of blood. All night, the government functioned out of the back parlor. Edwin Stanton, the Secretary of War, took charge. He was the one who famously said, "Now he belongs to the ages," though some historians like Adam Gopnik have argued he might have actually said "Now he belongs to the angels." Either way, the sentiment holds.

🔗 Read more: Robert Hanssen: What Most People Get Wrong About the FBI's Most Damaging Spy

Lincoln breathed his last at 7:22 AM on April 15. Technically, while the Abraham Lincoln date of assassination is the 14th, he became the first American president to be murdered on the morning of the 15th.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Conspiracy

We tend to think of Booth as a lone nut. He wasn't. He was part of a sophisticated cell of Confederate sympathizers. They had been planning to kidnap Lincoln for months to use him as a bargaining chip for POW exchanges. When the war ended, the plan shifted from kidnapping to murder.

- Mary Surratt: She ran the boarding house where they met. She became the first woman executed by the federal government.

- Lewis Powell: He was the giant of a man who tried to kill Seward. He was a terrifyingly efficient soldier.

- David Herold: The "guide" who helped Booth escape into the Virginia woods.

- George Atzerodt: The man who was supposed to kill the Vice President but got drunk instead.

If they had succeeded in killing all three—Lincoln, Johnson, and Seward—the line of succession would have been in total chaos. The North might have turned back toward total war against the South in a fit of rage.

The manhunt for Booth lasted 12 days. It was the largest search in U.S. history at the time. He was eventually cornered in a tobacco barn on the Garrett farm. He refused to come out. The Union soldiers set the barn on fire. Boston Corbett, a deeply religious and somewhat eccentric soldier, shot Booth through a gap in the boards, hitting him in the neck. Booth died paralyzed, looking at his hands and whispering, "Useless, useless."

The Lasting Trauma of the Assassination

The aftermath was brutal. The South, which might have received a "charitable" reconstruction under Lincoln's "malice toward none" policy, instead faced a vengeful Congress and the erratic leadership of Andrew Johnson. Johnson was a Southern Unionist who hated the planter class but had zero sympathy for the formerly enslaved.

The Abraham Lincoln date of assassination basically killed the best hope for a smooth transition into a post-slavery America.

💡 You might also like: Why the Recent Snowfall Western New York State Emergency Was Different

We see the ripples of that night even today. The racial tensions, the legislative battles over Reconstruction, the rise of the Jim Crow era—a lot of that was exacerbated because the man with the political capital to prevent it was taken off the board at the worst possible moment.

Modern Perspectives on the Site

If you go to Washington D.C. today, Ford’s Theatre is still there. It’s a National Historic Site. You can stand in the lobby and look at the clothes Lincoln was wearing that night—his black overcoat is preserved in a glass case. You can see the tiny derringer. It’s smaller than you think.

The Petersen House is also open to the public. Standing in that tiny back bedroom is an eerie experience. It makes the "Great Emancipator" feel very human, very vulnerable, and very mortal.

How to Properly Commemorate the History

If you're looking to dive deeper into this specific moment in time, don't just stick to the basic history books.

- Visit the National Museum of Health and Medicine: They actually have the lead ball that killed Lincoln and fragments of his skull. It’s morbid, but it brings the reality of the violence home in a way words can't.

- Read "Manhunt" by James L. Swanson: This is probably the definitive minute-by-minute account of the 12-day chase for Booth. It reads like a thriller.

- Check out the Surratt House Museum: Located in Clinton, Maryland, it gives a unique look into the conspirators' side of the story and how the escape route was planned.

- Examine the "Greatest Funeral in History": Lincoln’s body was taken on a massive train journey through 180 cities and seven states before being buried in Springfield, Illinois. Looking at the photos of these funeral processions shows just how much the country was reeling.

The Abraham Lincoln date of assassination isn't just a trivia point. It’s the moment the American experiment was nearly decapitated. Understanding the 14th of April requires looking past the legend of the log cabin and seeing the raw, messy, and violent reality of a country that was trying to heal but ended up being scarred for a century to come.

Take a moment to look at the primary sources from that week. Read the New York Herald's front page from April 15. The raw shock in the writing is palpable. That's where the real history lives—not in the polished textbooks, but in the frantic, heartbroken words of the people who lived through the night the lights went out in Washington.