You’ve probably seen the clickbait. Maybe it was a sleek 3D render of a vacuum-sealed pod screaming through a glass tube at 4,000 miles per hour. Or a headline claiming we’re just a decade away from "driving" across the Atlantic. It’s a captivating thought. Imagine grabbing a bagel in Manhattan and popping out in Piccadilly Circus just in time for a late lunch, all without touching a plane. But if we’re being honest, the dream of a tunnel New York to London is currently trapped somewhere between a fever dream and a massive engineering headache.

It isn't just about the distance. It’s about the physics of the abyss.

People often compare it to the Chunnel. The Channel Tunnel connecting the UK and France is an incredible feat of human grit, but it’s only 31 miles long. The distance between NYC and London is roughly 3,500 miles. That’s not just a little bit longer; it’s a different universe of complexity. To make a tunnel New York to London even remotely feasible, we aren't talking about digging a hole in the mud. We’re talking about spanning the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, dodging underwater volcanoes, and dealing with pressures that would crush a standard submarine like a soda can.

The Transatlantic Tunnel Concept: Fact vs. Science Fiction

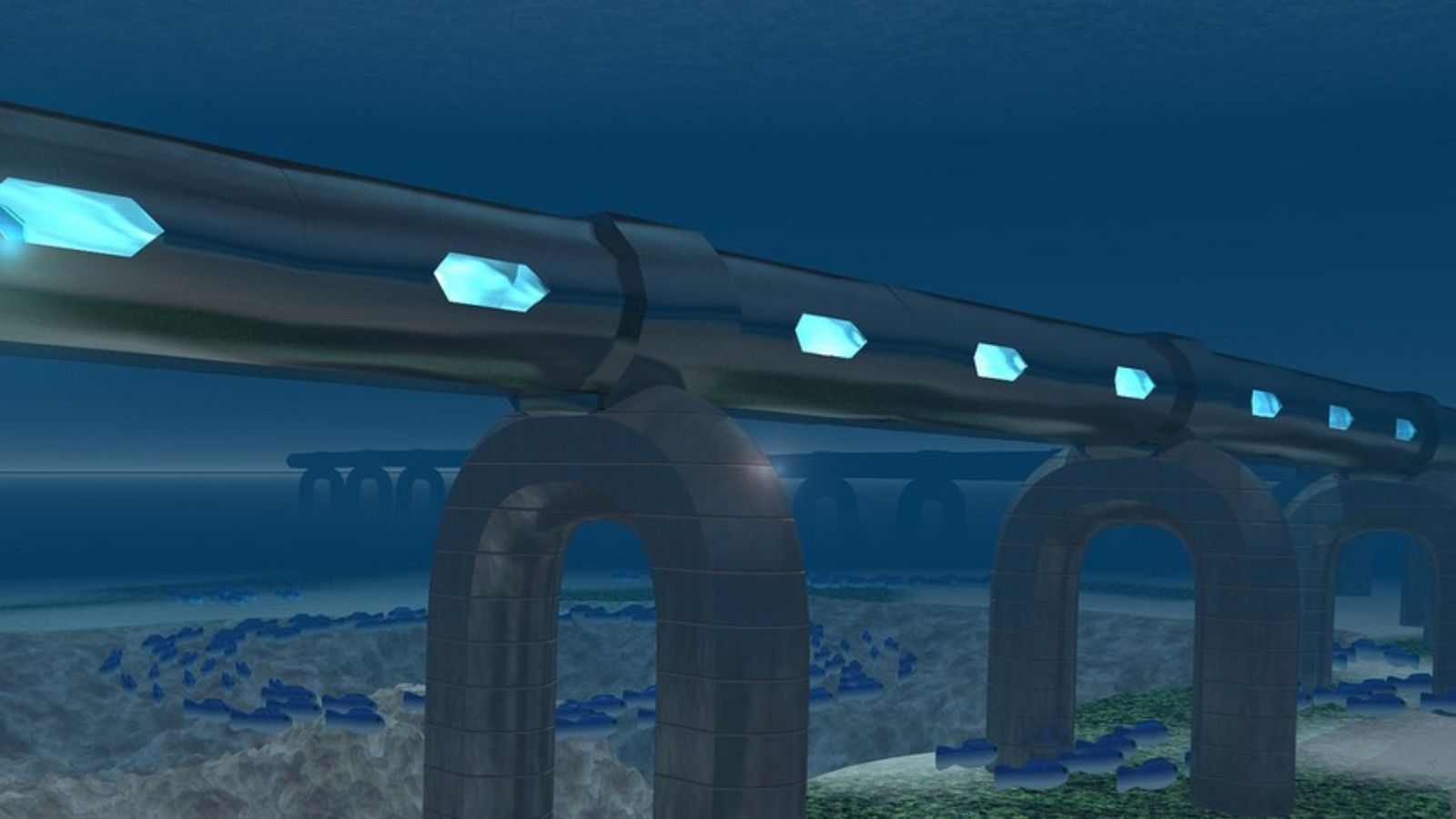

The idea usually gets lumped into the "vactrain" or Hyperloop category. Back in the 1970s, physicist Robert Salter at the RAND Corporation actually proposed a "Very High Speed Transit" (VHST) system. He wasn't some guy with a whiteboard and too much caffeine; he was a serious scientist. He envisioned a vacuum tube buried underground or anchored to the ocean floor. In a vacuum, there’s no air resistance. Without air resistance, you can theoretically travel at supersonic speeds. We’re talking New York to London in under an hour.

Sounds great, right?

The reality is a logistical nightmare. The Atlantic Ocean is deep. In some spots, it’s over 12,000 feet deep. You can't just drop a pipe on the bottom. The pressure at those depths is around 5,000 pounds per square inch. If a tiny crack formed in your 3,500-mile-long tube, the incoming water wouldn't just leak—it would hit the train with the force of an explosion.

📖 Related: Access Deleted Messages iPhone: How to Actually Get Your Texts Back Without Getting Scammed

Why the ocean floor is a "no-go" zone

Most people think the bottom of the ocean is a flat, sandy plain. It’s not. It’s a jagged, mountainous mess. The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a massive underwater mountain range where tectonic plates are literally pulling apart. If you tried to lay a solid tunnel across that, the earth’s movement would snap it like a twig.

Some engineers, like those featured in Discovery Channel's "Extreme Engineering," have floated the idea of a submerged floating tunnel. Picture a giant pipe tethered to the sea floor by thousands of steel cables, floating about 100 to 150 feet below the surface. This would keep the tunnel away from the crushing pressures of the deep sea and the chaotic storms on the surface. But then you have a new problem: ships. The Atlantic is a highway for massive cargo vessels and nuclear submarines. One stray anchor or a navigation error, and you have a global catastrophe.

The Trillion Dollar Price Tag

Let’s talk money. Because honestly, money is usually the bigger wall than the physics. The Chunnel cost about £9 billion in 1994, which is over £20 billion today. And that was for 31 miles. A tunnel New York to London is over 100 times that length.

- Material Costs: You’d need tens of millions of tons of high-grade steel and reinforced concrete.

- The Vacuum Problem: Maintaining a vacuum over 3,500 miles is something we can’t even do on land yet. Elon Musk’s Hyperloop projects have struggled with much shorter distances.

- Energy: The amount of electricity required to power the magnetic levitation (maglev) tracks and the vacuum pumps would require several dedicated nuclear power plants.

Estimates for a project like this usually start at $12 trillion and go up from there. For context, the entire GDP of the United States is around $27 trillion. No government is going to spend half their annual economic output so you can avoid a 7-hour flight and some mediocre airplane chicken.

The Human Factor: Would You Actually Get On It?

Safety is a weird thing. We trust planes because we’ve had a century to perfect them. If a plane has an engine failure, it can often glide. If a maglev train traveling at 2,000 mph in a vacuum tube has a "glitch," there is zero margin for error.

How do you evacuate? You’re in the middle of the Atlantic, 1,500 miles from either coast, in a pressurized tube under the water. You can’t just have "emergency exits." Any door would have to lead to some kind of escape pod system that could survive the ascent to the surface. It’s a claustrophobe’s worst nightmare.

And then there's the heat.

Moving a train at those speeds, even with maglev, creates heat. In a vacuum, heat has nowhere to go. There’s no air to carry it away. Without a massive, incredibly complex cooling system, the tunnel would essentially become a 3,500-mile-long oven.

Is There Any Real Progress?

Not really. Not for a full-scale Atlantic crossing.

💡 You might also like: Schneider Electric Data Center News: Why AI Is Forcing a Total Redesign

However, we are seeing "baby steps" in the technology. China is currently testing high-speed maglev trains that can hit 600 km/h (about 370 mph). In Europe, there’s constant talk about expanding the rail network to replace short-haul flights. But the leap from a 300-mile land route to a 3,500-mile undersea route is massive.

Companies like Virgin Hyperloop (which pivoted away from passenger travel recently) and Hardt Hyperloop in the Netherlands are proving the tech works on a small scale. But even they admit that the infrastructure costs are the primary barrier. Boring a hole is expensive. Maintaining it is even worse.

What Most People Get Wrong About This Project

A lot of folks think we’re just "not trying hard enough." They point to the moon landing as proof that we can do anything. But the moon landing was a weight problem and a fuel problem. A tunnel New York to London is a materials science problem that we haven't solved yet.

We don't have a material that is light enough to float, strong enough to resist the pressure, and flexible enough to survive tectonic shifts over thousands of miles. Until we discover some kind of "wonder material" (maybe graphene-based composites or something we haven't even dreamed up yet), the blueprints are going to stay in the drawer.

The "Green" Argument

Ironically, the best shot this project has is the environment. Aviation is a huge carbon emitter. If the world gets serious about banning long-haul flights to save the planet, a carbon-neutral maglev tunnel starts to look slightly less insane. If it’s powered by offshore wind and tidal energy, it could theoretically be the cleanest way to cross the pond. But again, the carbon footprint of building the thing would be so massive it might take a century to "break even" on emissions.

Actionable Insights: What to Watch Instead

Since you won't be booking a ticket on the Atlantic Express anytime soon, here is what is actually happening in the world of high-speed travel that you can keep an eye on:

- The Boom Overture: This is a supersonic passenger jet currently in development. It’s the "spiritual successor" to the Concorde. Instead of a tunnel, it uses the air. It aims to cut the NYC to London flight time down to about 3.5 hours. It’s much more likely to happen in our lifetime than a tunnel.

- Maglev Expansion in East Asia: If you want to see the tech that would power a New York to London tunnel, look at the L0 Series Maglev in Japan. It’s clocked in at 374 mph. That’s the real-world baseline.

- Submerged Floating Bridges: Keep an eye on Norway. They are looking into "SFTs" (Submerged Floating Tubes) to cross their deep fjords. If they can successfully build a mile-long version, it proves the concept for the Atlantic.

The tunnel New York to London remains the "Holy Grail" of transit. It’s a beautiful, impossible idea that keeps engineers awake at night. For now, keep your passport ready and stick to the airlines. The ocean is just too big, too deep, and way too expensive to conquer with a shovel.

If you are genuinely curious about how this might eventually work, look into the developments of the "Iron Silk Road" and China's investments in ultra-high-speed rail. The scale of their infrastructure projects is the closest thing we have to a roadmap for a transatlantic attempt. Watch the materials science space—specifically advancements in carbon nanotubes—as that's the only way we'll ever get a tube strong enough to survive the deep. For the next few decades, the only way you're crossing the Atlantic underwater is in a submarine, and they don't serve drinks.