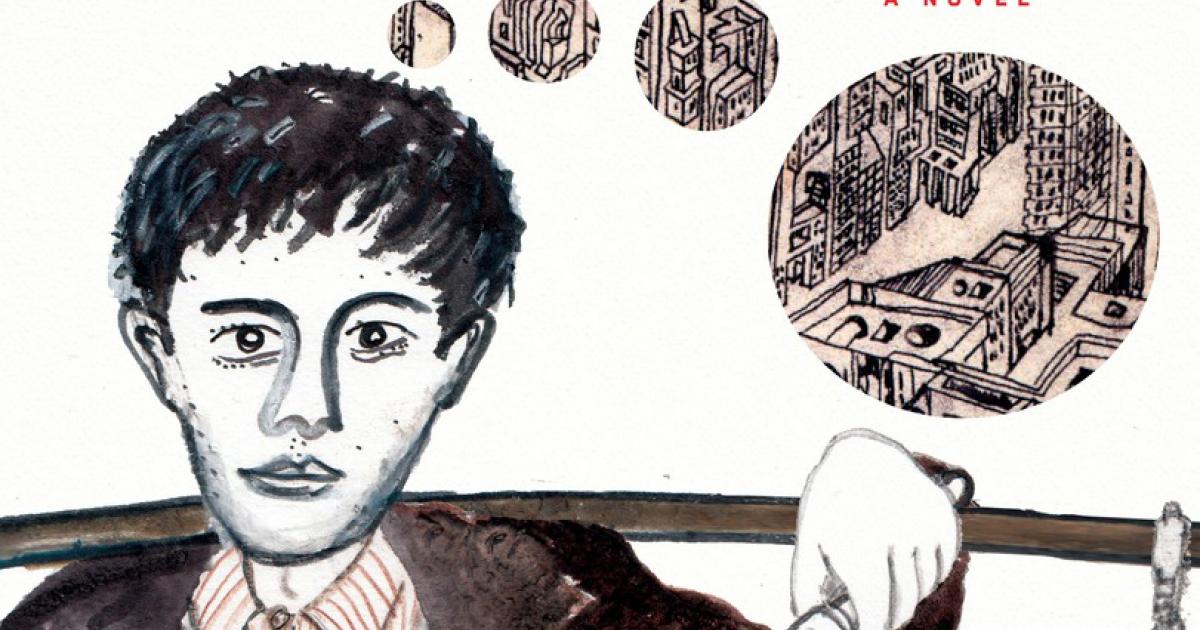

Istanbul is a monster of a city. It swallows people whole, reshapes them, and then spits them back out onto the cobblestones of Beyoğlu or the muddy outskirts of Tarlabaşı. If you’ve ever picked up a copy of A Strangeness in My Mind by Orhan Pamuk, you know exactly what I’m talking about. This isn't just some dry, historical slog through the 20th century. It’s a messy, loud, deeply personal look at how a city changes while the people inside it try to keep their heads above water.

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about Mevlut Karataş. He's the heart of the book. Honestly, he’s one of the most relatable "losers" in modern literature, though calling him a loser feels a bit mean. He’s a street vendor. He sells boza—that thick, fermented grain drink that tastes like a mix of yogurt and beer—and he walks the streets for decades while Istanbul transforms from a dusty collection of neighborhoods into a neon-lit megalopolis.

Why do we still care about a book published back in 2014? Because the "strangeness" Pamuk describes hasn't gone away. If anything, it’s gotten more intense.

The Reality of the Gecekondu

Most people think of Istanbul as blue mosques and fancy carpets. Pamuk shows us the gecekondu. These were "built overnight" houses. Literally. In the 1950s and 60s, if you could get a roof over a structure before the authorities saw you, it was yours. Mevlut and his father live this reality. It’s a world of mud, lack of electricity, and the constant threat of demolition.

It’s interesting because this isn't just fiction. Scholars like Asu Aksoy have written extensively about how these informal settlements defined the urban sprawl of Turkey. Pamuk captures the vibe perfectly. You feel the dampness in the walls. You smell the coal smoke.

Mevlut isn't a revolutionary. He’s just a guy. He wants a wife. He wants to sell his boza. But the world around him is obsessed with politics—Leftists vs. Nationalists, Secularists vs. Islamists. There’s a scene where he’s just trying to navigate the streets while people are literally shooting at each other over ideology. It’s chaotic. It’s real. It reminds me of that quote from the British historian Arnold Toynbee, who described Istanbul as a "pivot of civilizations." In this book, that pivot feels like a grinding gear.

That Infamous Elopement Gone Wrong

Let's talk about the letter. This is the pivot point of the whole narrative. Mevlut falls in love with a girl he sees at a wedding. He writes her love letters for years. Intense, burning letters. Eventually, he elopes with her in the dark of night, only to realize—once the sun comes up—that he’s actually run off with her older sister, Rayiha.

🔗 Read more: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

It’s a comedy of errors that feels like a gut punch.

Most authors would make this a tragedy. They’d make Mevlut bitter. But Pamuk does something weirder and more human. Mevlut decides to love Rayiha anyway. He chooses the reality over the fantasy. There’s a psychological depth here that echoes the work of Sigmund Freud regarding "The Uncanny" (Das Unheimliche). The strangeness in Mevlut’s mind is the gap between what he sees and what he feels. He walks the streets at night because the darkness allows him to bridge that gap.

He likes the shadows.

The boza itself is a symbol. By the 1990s, nobody really needs boza. You can buy soda, beer, or bottled water. But Mevlut keeps walking. He shouts "Boo-zaaa!" into the night air. It’s a performance of nostalgia. Pamuk is showing us that as cities modernize, we cling to these useless, beautiful rituals just to feel like ourselves.

How Istanbul Became a Character

You can't separate the plot from the geography. If you look at maps of Istanbul from 1969 versus 2012, it’s unrecognizable. The population exploded from about 2 million to over 13 million during the span of the novel.

Pamuk uses Mevlut as a human measuring stick.

💡 You might also like: Why Grand Funk’s Bad Time is Secretly the Best Pop Song of the 1970s

- The 70s: Political violence and the rise of the apartment block.

- The 80s: The military coup and the influx of consumerism.

- The 90s: The struggle between the old religious guard and the new globalists.

- The 2000s: Construction. So much construction.

Critics often compare Pamuk to James Joyce because of how he maps the city. But where Joyce’s Dublin is frozen in a single day, Pamuk’s Istanbul is a living organism that’s constantly shedding its skin. Mevlut is the flea on the back of that organism. He sees the high-rises go up where there used to be fields. He sees his cousins get rich through shady real estate deals while he stays poor.

There’s a specific nuance here regarding "Hüzün." This is a Turkish word that doesn't quite translate to "melancholy." It’s a collective sense of loss. It’s the feeling of living among the ruins of a great empire while trying to be modern. A Strangeness in My Mind is the ultimate exploration of Hüzün.

Misconceptions About the Book

Some readers get frustrated with Mevlut. They want him to "win." They want him to realize he was tricked by his cousins and fight back. But that’s missing the point. Mevlut’s "victory" is his inner life. He’s the only one who actually sees the city. Everyone else is too busy trying to own it.

Also, it's not a romance. People see the "love letters" plot and expect Nicholas Sparks. Forget that. It’s a book about urban planning, fermented wheat, and the weird way our brains justify the choices we make.

The perspective shifts are another thing that trips people up. One chapter is Mevlut’s third-person narrative, the next is his cousin Süleyman breaking the fourth wall to complain about Mevlut. It’s polyphonic. Pamuk used a similar technique in My Name is Red, but here it feels more like a crowded dinner table where everyone is talking over each other. It’s messy because life is messy.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Reader

If you're going to dive into this 600-page beast, or if you've already read it and are feeling that post-book void, here is how to actually digest it:

📖 Related: Why La Mera Mera Radio is Actually Dominating Local Airwaves Right Now

Look at your own "Strangeness."

We all have a public view and a private view. Mevlut calls this the "intent of the heart" versus the "intent of the words." Think about the things you do just because they are expected of you, versus the things you do because they make your soul feel quiet. That’s where the "strangeness" lives.

Walk your city differently.

Mevlut’s power comes from his feet. He knows the cracks in the sidewalk. Next time you're out, turn off the podcast. Put the phone away. Walk a route you know well but look at the upper stories of the buildings. Notice what has changed in the last five years. Cities are layers of history, and we usually only see the top one.

Understand the Boza.

Research the history of fermented drinks. It sounds boring, but the sociology of food is fascinating. Boza was popular because it was technically non-alcoholic (mostly), allowing it to bypass religious restrictions while still providing a slight buzz and a lot of calories. It was the "energy drink" of the Ottoman working class.

Read the Map.

Get a physical or digital map of Istanbul. Locate the hills of Kısıklı and the valley of Tarlabaşı. Seeing the elevation and the distance Mevlut walked every night makes his dedication—and his loneliness—feel much more visceral.

The book ends not with a grand explosion, but with a quiet realization. Mevlut realizes that even though he was tricked, even though he stayed poor, and even though the city he loved is gone, he was happy. Not because things went his way, but because he was present for all of it. In a world of "hustle culture" and "optimization," that’s a pretty radical lesson to take home.