Space is usually quiet. It’s a vacuum, after all. But every once in a while, something happens that is so loud—at least in terms of electromagnetic radiation—that it shakes our entire understanding of how the universe works. I'm talking about a star eating black hole. Astronomers call these "Tidal Disruption Events" or TDEs. Basically, a star wanders a little too close to the wrong neighborhood and gets ripped into spaghetti by gravity. It’s messy. It’s fast. Honestly, it’s one of the most terrifying things happening in the dark corners of our galaxy.

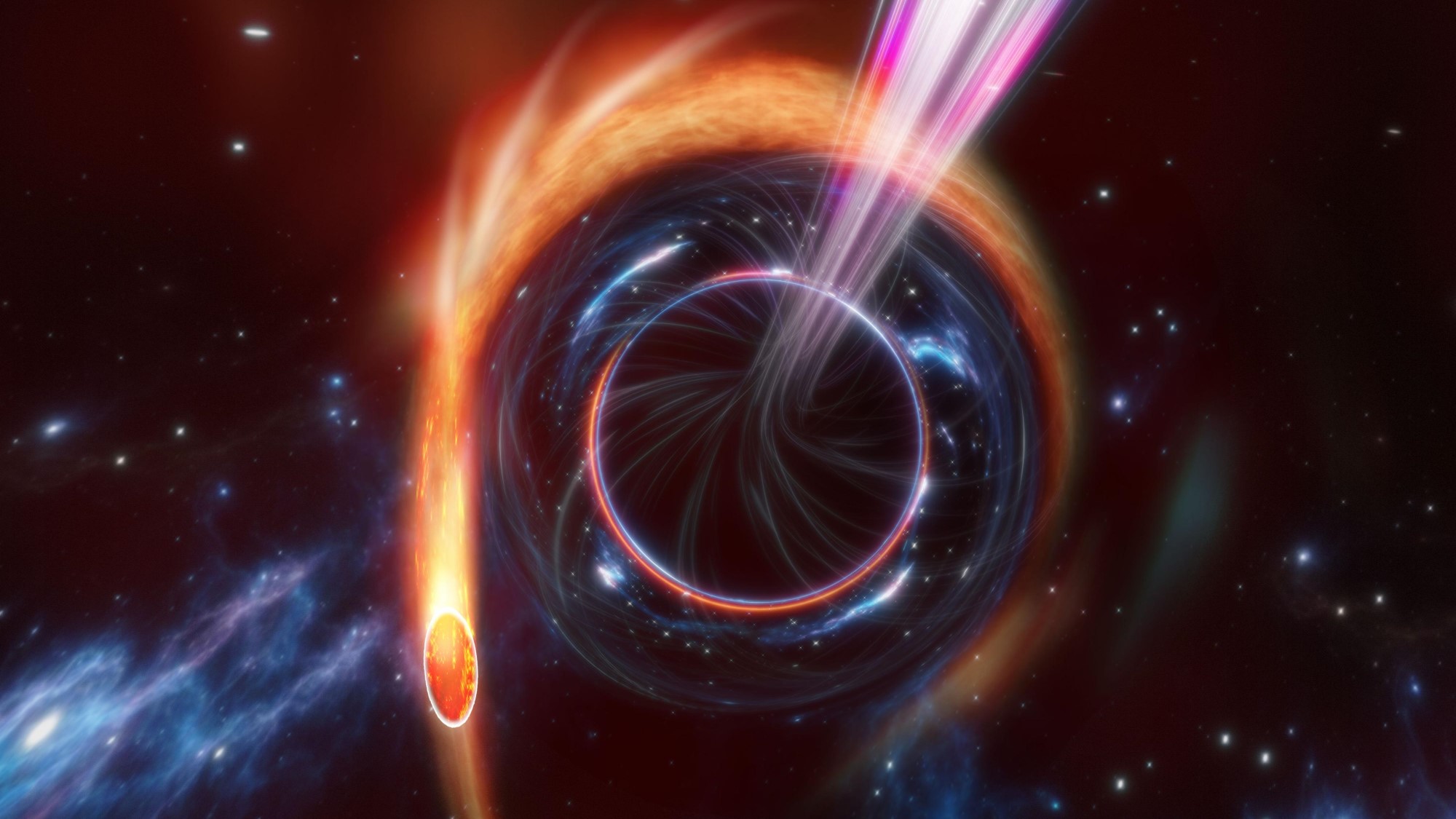

Most people think black holes are like cosmic vacuum cleaners. They aren't. They don't just "suck" things in from across the room. You have to actually fall into them. But when a star's orbit brings it within the "tidal radius" of a supermassive black hole, the gravity on the near side of the star is so much stronger than the gravity on the far side that the star simply ceases to be a sphere. It stretches. It breaks. It turns into a stream of hot, screaming gas.

The Physics of a Star Eating Black Hole: Spaghettification is Real

When we say a star eating black hole is "eating," we’re being a bit metaphorical. It’s more like a woodchipper. This process is known as spaghettification. Sir Martin Rees, a name you’ll see in almost every serious paper on this topic, was one of the first to really lay out how this works back in the 1980s.

Imagine a star like our Sun. It’s held together by its own gravity. Now, put it near a monster with the mass of four million Suns, like Sagittarius A* at the center of our own Milky Way. The gravitational pull becomes so uneven across the body of the star that the internal "glue" fails.

The star gets pulled into a long, thin strand of stellar guts. About half of that material gets flung out into space at incredible speeds. The other half? That’s the "meal." It loops back around, colliding with itself and forming a glowing disk of debris called an accretion disk. This is where the light comes from. The friction and gravity heat that gas to millions of degrees. It glows in X-rays. It glows in ultraviolet. It’s a lighthouse that tells us, "Hey, a star just died here."

Why AT2018fyk Changed Everything

For a long time, we thought these were one-and-done events. The star dies, the black hole glows for a few months or years, and then things go dark again. But then came AT2018fyk. This was a specific star eating black hole event tracked by researchers like Thomas Wevers using the eROSITA telescope.

What happened? The black hole ate. Then it stopped. Then, about two years later, it started eating again. This shouldn't happen if the star was totally destroyed. What we’re seeing now is a "partial" tidal disruption. The black hole is taking bites. It’s a repeat offender. It’s stripping layers off a star every time it passes by in an elliptical orbit. It's basically cosmic torture. This discovery flipped the script because it means there are likely thousands of "zombie" stars out there, slowly being peeled like an onion every few years until nothing is left.

👉 See also: Why are US flags at half staff today and who actually makes that call?

Detection: How We Actually Catch a Star Eating Black Hole in the Act

We can't see black holes. Obviously. But we can see the crime scene.

In 2026, our tools for catching a star eating black hole are better than ever. We use the Vera C. Rubin Observatory and the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF). These telescopes scan the sky every night, looking for things that "flicker." When a galaxy that was previously dim suddenly flares up with the brightness of a billion suns, astronomers scramble.

- The Flare: A sudden spike in UV and X-ray light.

- The Temperature: TDEs stay hot for a long time, unlike supernovae which cool down relatively quickly.

- The Location: It has to happen in the very center of a galaxy. If the flare is off to the side, it's probably just a regular star exploding.

It’s about context.

Suvi Gezari, a lead scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute, has spent years categorized these. One of the weirder things they've found is that some black holes "burp" after they eat. They launch jets of matter at nearly the speed of light. This isn't the star being swallowed; it's the black hole's magnetic fields acting like a high-pressure hose, blasting material away before it can cross the event horizon.

What Most People Get Wrong About Stellar Consumption

You’ve probably seen the CGI movies. A black hole looks like a dark hole in the sky. In reality, a star eating black hole is the brightest object in its neighborhood.

It’s an efficiency thing.

✨ Don't miss: Elecciones en Honduras 2025: ¿Quién va ganando realmente según los últimos datos?

Nuclear fusion—what stars do to stay alive—converts about 0.7% of mass into energy. Accreting onto a black hole? That can convert up to 40% of mass into energy. It is the most efficient power plant in the universe. If you were nearby (which you shouldn't be), the light would be blinding. You aren't looking at darkness; you're looking at a disk of superheated plasma that outshines the rest of the galaxy combined.

Also, size matters. Ironically, if a black hole is too big—say, over 100 million times the mass of the Sun—it doesn't actually "eat" the star in a flashy way. The event horizon is so large that the star passes through it whole before the tidal forces can rip it apart. The star just... disappears. No flare. No light. Just gone. Like a ghost. For a TDE to be visible, the black hole has to be "small" enough to shred the star outside the point of no return.

The Mystery of the "Missing" Light

There is a big debate in the community right now about "optical" vs "X-ray" TDEs. Some star eating black hole events show up beautifully in optical telescopes (the stuff we see with our eyes), but they don't show much X-ray radiation.

Why?

Some think it's because of "shrouding." The debris from the star forms a thick cloud around the black hole, absorbing the X-rays and re-emitting them as visible light. It's like a cosmic lampshade. Others think it’s about the shocks. When the gas stream circles back and hits itself, it creates massive shockwaves that glow in the optical spectrum before the gas even settles into a disk. We’re still arguing about this. It's a messy field of study because every event seems to have its own "personality."

Practical Insights: What This Means for Us

You might be wondering why we care about a star eating black hole billions of light-years away. It’s not just for the cool pictures.

🔗 Read more: Trump Approval Rating State Map: Why the Red-Blue Divide is Moving

First, these events are the only way we can study "dormant" supermassive black holes. Most black holes aren't doing anything. They're just sitting there in the dark. We can't measure their mass or their spin. But when they eat a star, they light up, providing a temporary laboratory for us to measure gravity in its most extreme form.

Second, it tells us about the "population" of stars in the centers of galaxies. If we see a lot of TDEs, it means the galactic center is crowded. If we see very few, it’s a desert.

Actionable Steps for Amateur Astronomers and Space Fans

If you want to keep up with these events without needing a PhD, here is how you do it:

- Follow the Open TDE Catalog: There is a literal database of every confirmed star eating black hole event. It’s updated in real-time as new flares are detected.

- Monitor NASA’s Swift and NICER Missions: These are the primary satellites that "see" the X-ray screams of dying stars. Their public alerts are often the first sign of a new discovery.

- Look for "Transient" News: Use keywords like "Tidal Disruption Event" or "Transient" in science news aggregators.

- Use Apps like 'SkySafari': Sometimes, if a TDE is bright enough and close enough (rare, but possible), it can be seen with high-end amateur gear. You'll want to know exactly which galaxy to point your scope at.

The universe is a violent place. A star eating black hole is the ultimate reminder that nothing—not even a sun—lasts forever. We are lucky enough to live in an era where we can actually watch the show.

If you're looking for the next big discovery, keep an eye on the "ASASSN" (All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae) alerts. They’ve been responsible for catching some of the most dramatic stellar deaths in recent years. The physics is complex, the scale is hard to wrap your head around, but the result is simple: a star gets too close, the black hole wins, and we get a front-row seat to the most energetic event in the cosmos.

The next time you look at a clear night sky, just remember: somewhere out there, a star is currently being turned into spaghetti. It's happening right now. We're just waiting for the light to reach us.

To dive deeper into the specific mechanics of how gravity warps spacetime during these events, you should look into the "Kerr Metric." It describes spinning black holes, and most of these "eaters" are spinning fast. That spin changes how the star's debris behaves, creating "precession" where the gas wobbles like a dying top. It’s the kind of detail that turns a simple "eating" story into a complex puzzle of general relativity. Keep looking up, because the most interesting things are often the ones that are trying to hide in the dark.