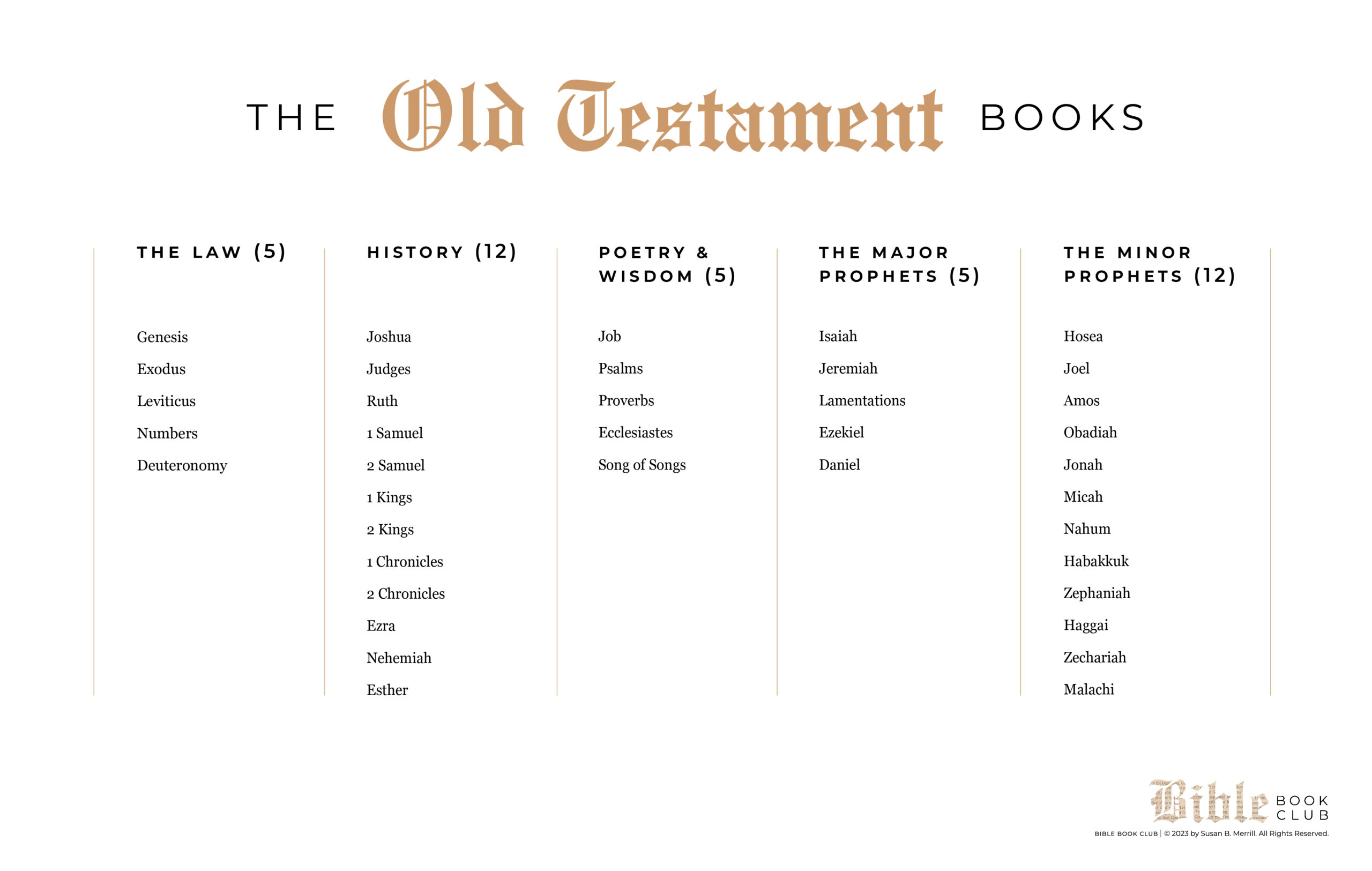

You’ve probably opened a Bible at some point and felt that immediate, overwhelming sense of "where do I even start?" It's a massive library. Not just a book, but a collection of 39 different works (at least in the Protestant tradition) that span centuries of history, poetry, and gritty legal codes. If you're looking for a list of the books of the old testament, you’re basically looking at the foundation of Western literature. But honestly, it’s not just a dry inventory. It’s a messy, beautiful, and sometimes confusing roadmap of ancient Near Eastern life.

Most people think the books are in chronological order. They aren't. Not even close. If you read them from front to back thinking you're getting a linear timeline, you're going to get lost somewhere around Leviticus and stay lost until you hit the Gospels. The arrangement is actually topical. It’s grouped by the type of writing—history with history, poetry with poetry.

The Five Books of Moses: The Pentateuch

We start with the heavy hitters. Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. This is the Torah. In Hebrew tradition, these are the most sacred. Genesis is where the "everything" starts—creation, the fall, and the patriarchs like Abraham and Jacob. Then you hit Exodus, which is essentially an ancient action movie about a mass escape from Egypt.

Then comes Leviticus.

Let’s be real: Leviticus is where most "read the Bible in a year" plans go to die. It’s a dense manual of priestly regulations and sacrifice rituals. It’s hard to get through. But if you skip it, you miss the cultural DNA of the ancient Israelites. Numbers follows with a mix of census data and wilderness wandering stories, and Deuteronomy wraps it up as a long series of farewell speeches by Moses. He’s basically reminding the people not to mess up once they cross the river. It’s repetitive because it’s a sermon.

💡 You might also like: Virgo Love Horoscope for Today and Tomorrow: Why You Need to Stop Fixing People

Tracking the History: Joshua to Esther

Once Moses is off the scene, the list of the books of the old testament moves into the historical books. This is where the narrative picks back up. Joshua and Judges cover the messy, often violent conquest of the Promised Land. If you’re looking for "happily ever after," you won't find it here. It’s a cycle of rebellion and rescue.

Then we get into the kings. 1 and 2 Samuel, 1 and 2 Kings, and 1 and 2 Chronicles.

Why are there two of each? Mostly because the original scrolls were too long to fit on one piece of parchment. It’s a practical limitation of ancient tech. 1 and 2 Samuel give us the rise of David, the shepherd boy who became a legend. 1 and 2 Kings track the slow, painful decline of the nation into civil war and eventual exile. Chronicles is sort of a "remix" of that same history, written later with a more hopeful, religious spin. After the exile, we have Ezra and Nehemiah, which deal with rebuilding a broken city, and Esther, which is a wild story about a queen saving her people without ever actually mentioning the word "God."

The Wisdom and Poetry Books

- Job: A gut-wrenching philosophical debate about why bad things happen to good people.

- Psalms: An ancient songbook. It covers every emotion from ecstatic joy to "I hate my enemies" rage.

- Proverbs: Short, punchy advice. Basically ancient Twitter but actually useful.

- Ecclesiastes: A surprisingly cynical look at the meaning of life. The author basically says everything is "hevel"—meaningless or like a vapor.

- Song of Solomon: It’s a love poem. And yeah, it’s pretty spicy for a religious text.

The Major Prophets: The Giants of the Canon

When we talk about the Major Prophets, we aren't saying they are more important than the others. They are just longer. Isaiah, Jeremiah, Lamentations, Ezekiel, and Daniel. These guys were the social critics of their day. They weren't just predicting the future; they were yelling at people in the present to stop oppressing the poor and start acting right.

📖 Related: Lo que nadie te dice sobre la moda verano 2025 mujer y por qué tu armario va a cambiar por completo

Isaiah is massive. 66 chapters of complex poetry and prophecy. Jeremiah is known as the "weeping prophet" because, frankly, he had a rough life and his message was mostly "we’re about to get conquered." Lamentations is his funeral dirge for Jerusalem. Then you have Ezekiel, who had some of the most bizarre visions in literature—wheels in the sky and valleys of dry bones coming to life. Daniel is the one everyone remembers from Sunday school because of the lions' den, but the second half of the book is full of intense, apocalyptic imagery that heavily influenced later writers.

The Twelve: The So-Called Minor Prophets

The final section of the list of the books of the old testament contains twelve shorter books. In the Hebrew Bible, these were often grouped together on a single scroll called "The Twelve."

- Hosea

- Joel

- Amos

- Obadiah

- Jonah

- Micah

- Nahum

- Habakkuk

- Zephaniah

- Haggai

- Zechariah

- Malachi

Hosea is a heartbreak story used as a metaphor for God’s relationship with Israel. Amos is a scathing critique of economic injustice. Jonah is the famous one about the fish, though the real point of the story is Jonah’s annoyance that God is actually merciful to his enemies. The rest of them—like Nahum, Habakkuk, and Zephaniah—are often overlooked but contain some of the most intense language in the entire collection. They deal with the rise and fall of empires like Assyria and Babylon.

Finally, Malachi closes out the Protestant Old Testament. It’s a series of disputes between God and the people who have grown cynical and lazy in their faith. It ends with a promise of a "messenger" to come, which sets the stage for the New Testament 400 years later.

👉 See also: Free Women Looking for Older Men: What Most People Get Wrong About Age-Gap Dating

Why the Order Matters (and Why it Varies)

Depending on who you ask, the list of the books of the old testament might look different. If you’re looking at a Jewish Tanakh, the books are the same but the order is totally different. They end with 2 Chronicles, finishing on a note of returning home. The Christian order, which follows the Greek Septuagint, ends with Malachi to point forward to the story of Jesus.

Catholic and Orthodox Bibles also include "Deuterocanonical" books—like Tobit, Judith, and Maccabees. These are historical and wisdom books from the period between the testaments. Protestants generally moved them to a separate section called the Apocrypha or dropped them entirely during the Reformation. It wasn't about "deleting" the Bible; it was a debate over which books were originally written in Hebrew versus Greek.

Putting the Knowledge to Use

If you actually want to understand these books, don't try to read them like a novel. You'll fail. It's better to dive into one specific "genre" at a time. Start with the stories in Genesis or the grit of the historical books like 1 Samuel. If you're feeling philosophical, Ecclesiastes is surprisingly modern.

Next steps for exploring the text:

- Pick a Translation: If you want easy reading, try the NLT or NIV. If you want a more literal word-for-word study, go for the ESV or NASB.

- Use a Study Bible: You need the context. Knowing that the "Philistines" were a sea-faring people makes the stories of Samson and David make way more sense.

- Read Chronologically: Find a reading plan that reorders the books by when events actually happened. It changes the entire experience, especially seeing where the prophets fit into the timeline of the kings.

- Compare Traditions: Look at a Catholic Bible versus a Protestant one. Seeing the "extra" books like Wisdom of Solomon or 1 Maccabees provides a lot of historical bridge-work between the two testaments.

The Old Testament isn't just a religious relic. It's a library of human experience—failure, hope, law, and poetry—that has shaped the world for three millennia. Understanding the list is just the first step into a much larger, much weirder, and much more fascinating world.