Look at your dinner. If there’s a tomato on your burger, or a potato in your fries, or even a sprinkle of black pepper on your steak, you’re looking at a living picture of Columbian Exchange in action. It’s not just some dusty history book term. Honestly, it’s the reason the world looks, tastes, and breathes the way it does today.

History is messy.

When Alfred W. Crosby coined the term "Columbian Exchange" back in 1972, he wasn't just talking about ships and maps. He was talking about a biological explosion. Imagine two halves of a planet that had been separated for thousands of years suddenly slamming together. It wasn't just people meeting; it was seeds, viruses, bugs, and livestock.

The Visual Reality of a Transformed World

If you could see a time-lapse picture of Columbian Exchange impacts over five hundred years, the first thing you'd notice is the color change of the landscape. Before 1492, there were no horses roaming the American Great Plains. No cattle. No honeybees. Can you imagine North America without a single honeybee? They weren't there.

Europeans brought the "Old World" with them. They wanted their wheat, their grapes for wine, and their olives. But the hitchhikers were what really changed the scenery. Dandelions, for example, aren't native to the Americas. They arrived in the soil used as ballast in ships.

On the flip side, the "New World" sent back absolute powerhouses.

Think about Italy. We associate Italy with tomato sauce. But before the 1500s, there wasn't a single tomato in all of Europe. Not one. The Spanish brought them back from the Aztecs. At first, Europeans thought they were poisonous because they're part of the nightshade family. They were literally called "poison apples" and used as ornamental porch plants.

Why Your Kitchen is a Historical Map

You've probably got a "New World" pantry and don't even know it. Corn (maize), potatoes, cassava, and sweet potatoes all come from the Americas. These aren't just snacks. They are high-calorie miracles.

When the potato hit Northern Europe, it changed everything. It grows in thin soil where wheat dies. It hides underground from marauding armies who would burn grain fields. Because of the potato, the population of Ireland and Germany skyrocketed. It basically fueled the Industrial Revolution by providing cheap, dense calories for factory workers.

But it wasn't all just "yay, new snacks."

👉 See also: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

The Darker Side of the Exchange

We have to talk about the germs. It's the most tragic part of the picture of Columbian Exchange history. The Americas were, biologically speaking, an island. The people living there had no immunity to Afro-Eurasian diseases. Smallpox, measles, and influenza didn't just make people sick; they cleared out entire civilizations.

Estimates from historians like Noble David Cook suggest that in some areas, 90% of the indigenous population died within a century of contact.

It wasn't a fair fight.

While the New World got smallpox, the Old World got... well, there’s a long-standing debate about syphilis. Many researchers believe it traveled back to Europe with returning sailors. It first appeared in a major way during the French invasion of Naples in 1495. It was a brutal, disfiguring exchange of a different kind.

The Great Dying and Global Cooling

Here is a wild fact that sounds like sci-fi but is backed by Earth science. Some researchers, including those at University College London, suggest that the "Great Dying" caused by the Columbian Exchange actually cooled the planet.

How?

So many people died in the Americas that massive amounts of farmed land were abandoned. Forests grew back over millions of acres. Those trees sucked so much carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere that it contributed to the "Little Ice Age," a period of global cooling between the 16th and 19th centuries.

Your history teacher probably didn't mention that the death of indigenous farmers might have made London's River Thames freeze over.

Animals That Redefined Continents

If you draw a picture of Columbian Exchange logistics, you have to include the pigs.

✨ Don't miss: God Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: The True Story Behind the Phrase Most People Get Wrong

Columbus brought eight pigs on his second voyage in 1493. Within decades, there were thousands. Pigs are survivors. They escaped, went feral, and ate everything in sight—including the crops of indigenous people. They were like a biological bulldozer.

Then there are the horses.

It’s hard to picture the "Wild West" without horses, but they are a European import. For tribes like the Comanche and the Lakota, the horse was a revolutionary technology. It changed how they hunted buffalo and how they fought. It created an entirely new culture in a matter of generations.

Cash Crops and the Human Cost

Sugar.

If there is one plant that defines the tragedy of this era, it’s sugar cane. It’s not native to the Caribbean; it came from South Asia via the Mediterranean. But it loved the tropical climate of Brazil and the West Indies.

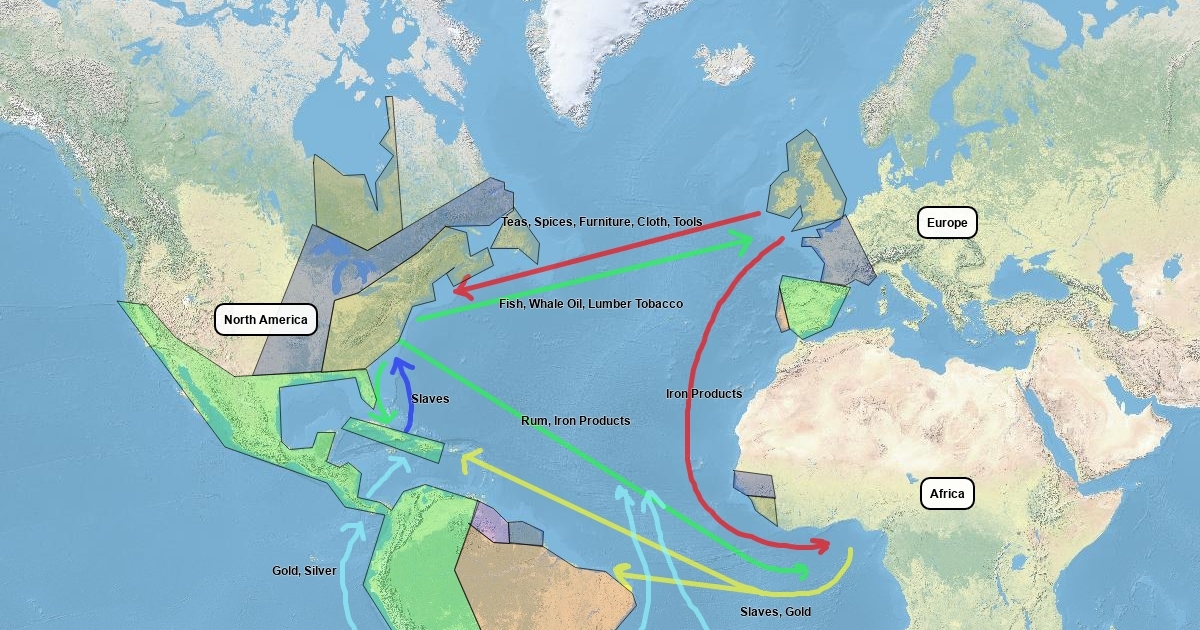

Sugar is labor-intensive. It’s dangerous to harvest. Because the indigenous populations had been decimated by disease, Europeans turned to the Transatlantic Slave Trade to fuel the sugar mills. This is where the picture of Columbian Exchange turns into a picture of systemic cruelty. The sweet tea in London was paid for by the forced labor of millions of Africans.

- Tobacco: A New World plant that became a global addiction.

- Coffee: An Old World plant (Ethiopia) that became a New World staple.

- Chocolate: Strictly an American luxury until the Spanish added sugar to it.

The Modern Picture of Columbian Exchange

We are still living in the "Homogenocene." That's a fancy word scientists use to describe our current era where everything is becoming the same everywhere.

When you go to a market in Thailand and see chilies, remember: chilies are from the Americas. There was no "spicy" Thai food or "spicy" Indian curry before the 1500s. They used black pepper or ginger. The introduction of the chili pepper changed the palate of half the globe.

Is this a good thing?

🔗 Read more: Kiko Japanese Restaurant Plantation: Why This Local Spot Still Wins the Sushi Game

Ecologically, it’s a disaster. We’ve lost thousands of local species because "global" species like wheat and cows take up all the space. But nutritionally, it’s the only reason we can support 8 billion people. Without the high-calorie crops of the Americas—specifically corn and potatoes—global population levels would likely be a fraction of what they are now.

Reality Check: Myths We Believe

Most people think the exchange was just a "discovery." It wasn't. It was an accidental biological war.

Also, don't think the Americas were a "wilderness." They were highly managed landscapes. The Amazon rainforest, in many parts, is actually a giant, overgrown orchard planted by indigenous people centuries ago. When the exchange happened, those managers were removed, and the "wild" took over.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you want to really "see" the picture of Columbian Exchange in your everyday life, try these steps:

Audit your spice cabinet. Look at where your food actually comes from. If you have vanilla, cocoa, or paprika, you're holding the spoils of the Americas. If you have cinnamon or cumin, that's the Old World.

Plant a heritage garden. Most "American" gardens are full of European flowers. Try planting milkweed, sunflowers, or squash—plants that have been here for millennia.

Read the source material. Don't just take a textbook's word for it. Check out 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created by Charles C. Mann. It’s arguably the best modern deep-dive into how this biological flip-flop created the world we live in.

Visit a local museum of indigenous history. Look at the tools used before the introduction of iron and steel. The level of sophistication in agriculture without the use of beasts of burden (like horses or oxen) is honestly mind-blowing.

The picture of Columbian Exchange isn't a static image in a gallery. It’s the coffee you drank this morning, the jeans you’re wearing (cotton trade!), and the very air we breathe. We are the products of a massive, unintentional experiment that started over 500 years ago and hasn't stopped since.