Music is weird. We're taught from day one that major scales are happy and minor scales are sad, but if you’ve ever sat down at a piano or picked up a guitar to actually write something, you quickly realize it's way more complicated than that. You start playing a minor key chords and suddenly you're in a world of "natural," "harmonic," and "melodic" variations that make your head spin. It’s not just about being "moody." It’s about how the math of the notes creates a specific kind of tension that our brains crave.

Honestly, the A minor scale is the best place to start because it’s the "white key" scale on the piano. No sharps, no flats. Just pure, unadulterated intervals. But here is what most people get wrong: they think they’re restricted to just A minor, D minor, and E minor. If you stay there, your music is going to sound like a dusty textbook.

The Basic DNA of A Minor Key Chords

In its purest form—what we call the Natural Minor or the Aeolian mode—the chords are built directly from the notes A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. If you stack thirds on those, you get a specific sequence. You've got your i chord (A minor), your ii° (B diminished—the one everyone ignores because it sounds "crunchy"), the III (C major), the iv (D minor), the v (E minor), the VI (F major), and the VII (G major).

It sounds fine. It’s the sound of 90s grunge and a lot of modern lo-fi hip hop. But there is a massive problem with the "natural" version of a minor key chords. The v chord (E minor) is weak. It doesn't "pull" you back to the A minor root very hard. In music theory, we call this the lack of a leading tone.

Think about it. In a C major scale, the B note is only a half-step away from C. It feels like it must resolve. In A natural minor, the note below A is G. That’s a whole step. It feels lazy. It feels unfinished. This is exactly why composers hundreds of years ago decided to "fix" the minor scale by raising that seventh note. This gives us the E major chord instead of E minor. Suddenly, your "sad" song has a major chord right in the middle of it that provides a massive, dramatic sense of urgency.

Why the Harmonic Minor Changes Everything

If you’ve ever listened to a Flamenco guitarist or a heavy metal solo by someone like Yngwie Malmsteen, you’re hearing the harmonic minor. By taking the G and making it a G#, you change the whole vibe of your a minor key chords palette.

👉 See also: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

Now, your "v" chord (E minor) becomes a "V" chord (E major or E7). This is the secret sauce. When you play an E7 and then drop into an A minor, it feels like coming home after a long, stressful day. It satisfies the ear. But there’s a trade-off. Raising that G to a G# creates a huge gap between the F and the G#. It’s an "augmented second," and it sounds very "snake charmer" or "Eastern European folk."

Some people love that. Others find it too jarring.

Breaking Down the "Standard" Choices

- The i chord (A minor): Your home base. It’s stable. It’s where the story begins and ends.

- The iv chord (D minor): This is the "subdominant." It’s like the middle of a sentence. It moves the story away from home but isn't as aggressive as the E chord.

- The VI and VII (F Major and G Major): These are your "epic" chords. If you’ve heard "All Along the Watchtower," you’ve heard the i-VII-VI progression (Am - G - F). It’s the bread and butter of rock music.

The Secret World of Borrowed Chords

Real experts don't stay in one lane. They "borrow" chords from other scales. This is where a minor key chords get really spicy. You might use a D major chord instead of a D minor. This comes from the A Dorian mode. It’s that "Oye Como Va" sound—slightly brighter, a bit more "Latin" or "Jazz" feeling. It takes the darkness of the A minor and adds a little ray of sunlight.

Then there’s the Neapolitan chord. In A minor, this would be a Bb major chord. It sounds incredibly dramatic and a bit "theatrical." It’s used heavily in classical music but also shows up in film scores when something tragic is happening.

You see, music isn't a set of rules. It’s a set of tools. If you only use the chords that "belong" in A minor, you’re painting with only three colors. The best songwriters—think Radiohead or even Taylor Swift—constantly drift between the different versions of the minor scale to keep your ears guessing.

✨ Don't miss: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

Why Does A Minor Feel Different?

Technically, A minor is the same "shape" as E minor or G minor, just shifted. But every key has a "flavor" due to the way instruments are built. On a guitar, A minor allows for those deep, ringing open strings (the A and the E). It feels resonant. On a piano, it’s the king of clarity.

There's a reason why some of the most famous pieces of music ever written, from "Fur Elise" to "Losing My Religion," are in A minor. It hits a sweet spot between being melancholic and being approachable. It’s not as "heavy" as C# minor, which feels like a funeral march, and it’s not as "ethereal" as B minor. It’s the "everyman" of minor keys.

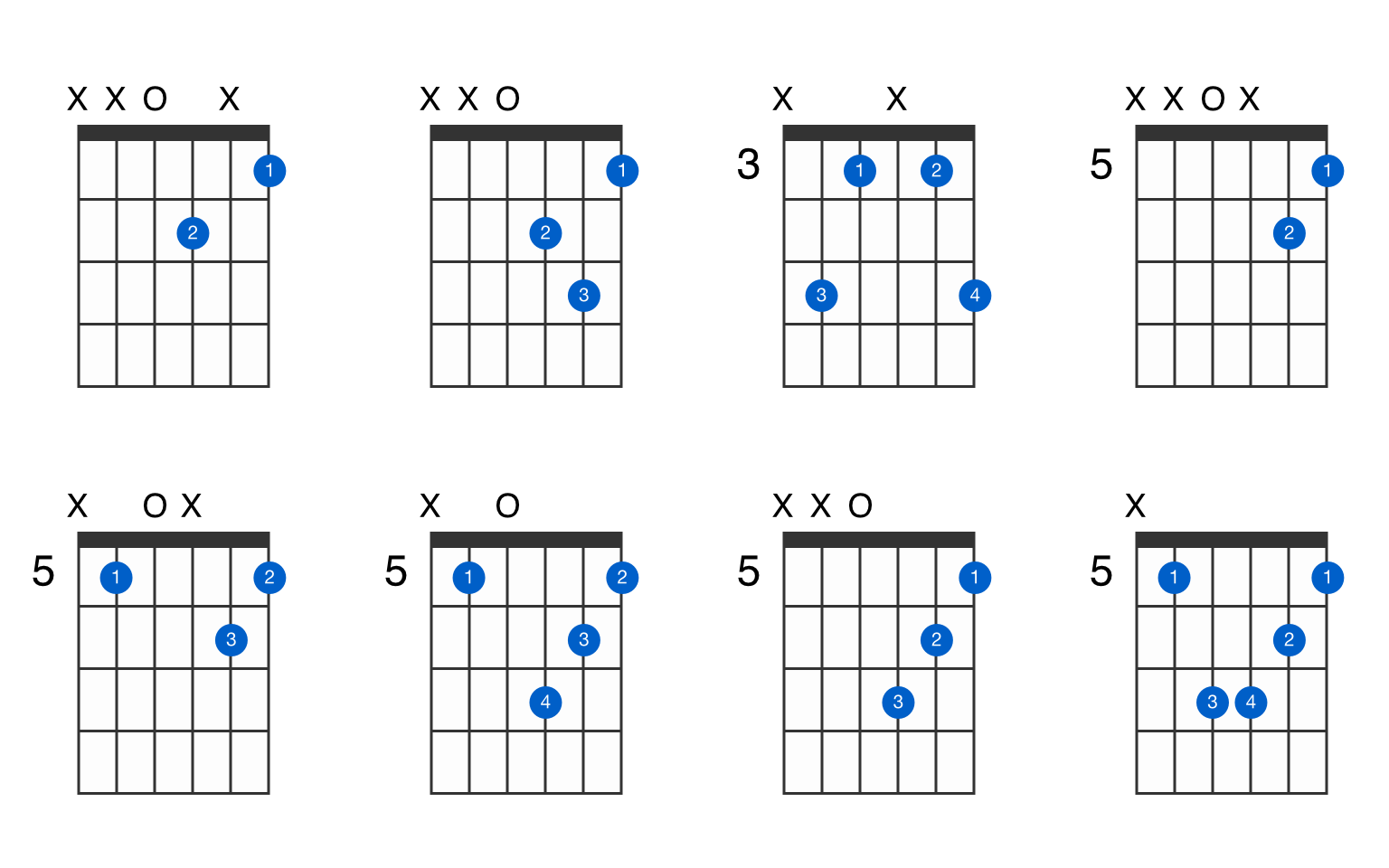

Common Progressions to Try Right Now

If you’re staring at a blank DAW or a notebook, stop overthinking. Use these tried-and-true frameworks for your a minor key chords and then tweak them.

The "Sad Pop" Loop: Am - F - C - G.

Wait, you might say, isn't C and G major? Yes. This is the "relative major" trick. C major is the "sister" scale to A minor. Using these together creates a bittersweet feeling that isn't purely depressing.The "Flamenco" Descent: Am - G - F - E.

This is often called the Andalusian Cadence. It feels like it’s constantly falling. It’s urgent, rhythmic, and incredibly satisfying to play.🔗 Read more: Alfonso Cuarón: Why the Harry Potter 3 Director Changed the Wizarding World Forever

The "Jazz Noir" Vibe: Am9 - Dm7 - E7alt - Am9.

Adding those "extension" notes (the 7ths and 9ths) softens the edges. It makes the chords feel smoky and sophisticated rather than just "sad."

Fact-Checking the "Sadness" of Minor Keys

It’s actually a bit of a myth that minor equals sad. In many cultures, minor-key music is used for celebratory dances. The Jewish "Hava Nagila" is a great example—it’s in a minor-based scale (Phrygian Dominant), but it’s the furthest thing from depressing. The "sadness" we associate with a minor key chords is largely a Western cultural construct, though the physics of the "minor third" interval does create a slower vibration that we tend to interpret as more subdued.

Research from the University of New South Wales suggests that we associate minor keys with sadness because they mimic the pitch drops in human speech when we are tired or upset. Major keys, conversely, mimic the rising inflection of someone who is excited. It’s biological as much as it is musical.

Moving Beyond the Three-Chord Trick

To truly master a minor key chords, you have to stop thinking of the scale as a fixed list. Think of it as a neighborhood. Most of the time, you stay in your house (A minor). Sometimes you go to your neighbor’s for a drink (D minor or F major). But every now and then, you should take a trip across town to a chord that "shouldn't" be there, like a B7 or a Bb major.

This is what creates "voice leading." If you can make the individual notes of your chords move smoothly—like a group of singers moving by only one or two steps at a time—the chords will sound professional, no matter how weird they are.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Song

- Swap the v for a V: Next time you’re playing A minor to E minor, change that E minor to an E major or E7. Feel that "pull"? That’s the leading tone (G#) wanting to go back to A.

- Use the F Major 7: Instead of a plain F major, add the open E string (if you're on guitar) or a B note if you want something "Lydian." It adds a "dreamy" texture to the A minor environment.

- The "Picardy Third" Finish: This is an old classical trick. Write your whole song in A minor, but for the very last chord, play an A major. It’s like the sun coming out behind clouds at the very last second.

- Experiment with the ii diminished: Don't be afraid of the B diminished chord (B-D-F). It sounds "wrong" in isolation, but if you use it to transition from A minor to E7, it acts as a perfect bridge.

The most important thing to remember about a minor key chords is that they are a playground. There is no "wrong" note if you know how to resolve it. Start with the basics, but don't stay there. Listen to how artists like Radiohead or Chopin use these chords to create "tension and release." That’s the real secret to music that moves people.