Let’s be honest. Most people think about nuclear weapons as one giant, vague "button" that someone might press if the world goes south. It’s scary. It’s abstract. But if you actually look at a list of nuclear missiles currently sitting in silos, submarines, and on the back of massive 16-wheel trucks, you realize the tech is incredibly specific, weirdly diverse, and, frankly, aging in ways that should probably concern us more than they do.

We aren't in the 1960s anymore. We’ve moved past the era where just having "the bomb" was the point. Now, it’s about delivery systems. It’s about how fast a piece of metal can re-enter the atmosphere without melting. It’s about whether a missile can zig-zag to dodge a multi-billion dollar interceptor.

The Heavies: Land-Based ICBMs

When you think of a "nuke," you’re probably picturing an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM). These are the giants.

The Minuteman III is the backbone of the U.S. land-based "triad." It’s old. It first went into service in 1970, and even though the guts have been swapped out a dozen times, the bones are ancient. It sits in underground silos across places like North Dakota and Wyoming. Its job is simple: fly up, hit space, and come back down thousands of miles away. It uses a solid-fueled rocket, which is great because you don't have to spend hours fueling it up before launch. You just flip the switch.

Across the pond—well, across the pole—you have the Russian RS-28 Sarmat, or what NATO calls the "Satan II." It’s a monster. Unlike the Minuteman, this thing is liquid-fueled, which usually makes a missile more temperamental, but the Sarmat is designed to carry up to 10 heavy warheads at once. Russia claims it can fly over either the North or South Pole, making it almost impossible to track with current early-warning systems designed for more direct routes. Is it as reliable as they say? Maybe. Testing has been... let's call it "eventful."

China’s DF-41 (Dongfeng-41) is the one that keeps Pentagon planners up at night. Why? Because it’s mobile. You can’t just point a satellite at a hole in the ground and watch it. These things are on launchers that look like oversized semi-trucks. They hide in tunnels. They move at night. With a range of about 9,300 miles, it can hit basically any spot in the continental U.S. from deep within the Chinese mainland.

The Stealthy Option: Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBMs)

If ICBMs are the loud, obvious threat, SLBMs are the ghosts.

The Trident II D5 is used by both the U.S. Navy and the British Royal Navy. It’s launched from Ohio-class (and soon Columbia-class) submarines. The cool—and terrifying—thing about the Trident is its accuracy. We’re talking about hitting a target within a few meters after traveling thousands of miles. It’s widely considered the most reliable missile in the world. When a sub disappears into the ocean, it becomes a "survivable" strike option. Even if a country gets wiped out in a first strike, the sub is still out there, waiting for the order to fire back.

Russia’s counterpart is the Bulava. It had a rocky start. For a few years, it felt like every other test launch ended in a spectacular firework show over the White Sea. But they’ve mostly ironed out the kinks. It’s designed to be launched from Borei-class submarines, and it’s specifically built to penetrate missile defenses by being "fast" off the line—shortening the boost phase where it’s most vulnerable.

The New Weird Stuff: Hypersonics and Cruise Missiles

The traditional list of nuclear missiles is changing because of "Hypersonic Glide Vehicles" (HGVs).

Most nuclear missiles follow a predictable arc, like a thrown baseball. Hypersonics don't. The Russian Avangard is basically a glider that sits on top of a traditional rocket. Once it hits the upper atmosphere, it detaches and screams toward the target at Mach 20 or higher. But instead of just falling, it maneuvers. It’s like trying to hit a dragonfly with a pebble from a mile away.

Then you have the Burevestnik (Skyfall). This one is genuinely bizarre. It’s a nuclear-powered cruise missile. Not just a missile with a nuclear warhead—a missile that uses a tiny nuclear reactor for propulsion. Theoretically, it could stay in the air for days or weeks, circling the globe until it finds a gap in defenses. It’s a bit of a "doomsday" weapon, and even Russian engineers have died in accidents trying to get the reactor tech to work. It’s high-risk, high-reward engineering in the most macabre sense.

Why the Tech Actually Matters

It’s easy to get lost in the stats. Range. Payload. Mach speed. But the nuances of these systems dictate global politics. For example, solid-fueled missiles (like the U.S. Minuteman or the North Korean Hwasong-18) are way more dangerous for stability. Why? Because they can be fired in minutes. Liquid-fueled missiles often need to be fueled right before launch, which gives satellites a chance to see what’s happening.

North Korea’s move toward the Hwasong-18 was a massive shift. Before that, their missiles were slower to prep. Now, they have something that can be hidden in a forest and fired before anyone can blink. That changes the "game theory" of a conflict. It makes everyone's trigger finger a little itchier.

The Aging Problem and the Cost of Staying Current

We’re at a weird crossroads. The U.S. is currently trying to replace the Minuteman III with a new missile called the Sentinel. It’s over budget. It’s behind schedule. People are asking: do we even need land-based missiles anymore? If the subs are so good, why keep the silos?

The argument for keeping them is the "warhead sponge" theory. It sounds grim because it is. If an enemy wants to take out the U.S. nuclear capability, they have to waste hundreds of their own warheads hitting silos in the Midwest. If we didn't have those silos, they’d only have to target a few ports and airbases. The list of nuclear missiles isn't just a list of weapons; it's a list of targets that keep other targets from being hit. It’s a circular, dark logic that has defined peace for eighty years.

Real World Examples of Current Arsenals

If you looked at a spreadsheet of what's out there right now, it would look something like this:

- United States: Roughly 400 Minuteman III ICBMs and a massive fleet of Trident II SLBMs. They are also developing the LRSO (Long-Range Stand-Off) cruise missile for B-52 bombers.

- Russia: A massive variety. Everything from the Topol-M (mobile) to the new Sarmat. They put a lot of money into "asymmetric" weapons like the Poseidon—a nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed underwater drone. It’s basically a giant autonomous torpedo.

- France: They don't do land-based missiles anymore. They focus entirely on the M51 SLBM. They want to make sure if they get hit, they can hit back from the sea.

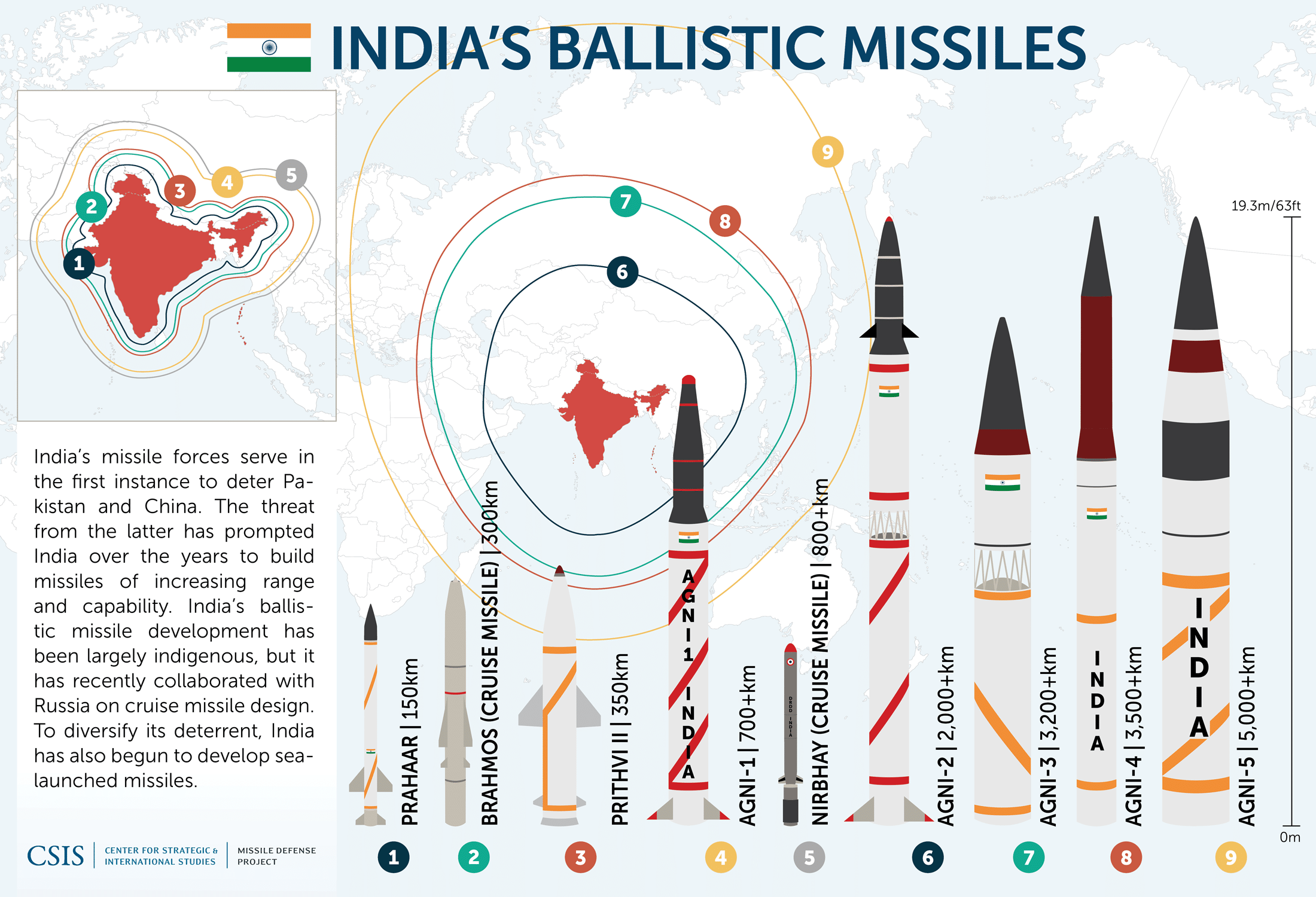

- India and Pakistan: Their missiles, like the Agni-V (India) and the Shaheen series (Pakistan), have shorter ranges compared to the big three, but they are modernizing fast. India is particularly focused on "canisterizing" their missiles—sealing them in tubes so they can be moved and fired quickly without much maintenance.

Understanding the Limitations

Let’s be real: none of this stuff is meant to be used. The moment a list of nuclear missiles turns into a list of "launches," the game is over. The tech is incredibly complex, but it's also prone to human error. There have been dozens of "broken arrows"—incidents where nukes were lost or almost fired by accident.

💡 You might also like: Why an iPhone XR Case with Card Holder is Still the Smartest Low-Tech Upgrade You Can Buy

In 1983, a Soviet officer named Stanislav Petrov saw his computer screen tell him the U.S. had launched five Minuteman missiles. He had to decide in minutes if it was a glitch or the end of the world. He guessed it was a glitch. He was right. The "list" is only as good as the sensors and the people watching them.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you're trying to keep track of this stuff without getting overwhelmed by propaganda or fear-mongering, here is how to stay informed:

Watch the "Nuclear Notebook." The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) publishes this regularly. Hans Kristensen and Matt Korda are basically the gold standard for tracking who has what. They don't guess; they use satellite imagery and budget documents to count.

Focus on "Delivery" not just "Warheads." A warhead in a warehouse is a liability. A warhead on a Yars mobile launcher is a strategic asset. When you see news about a "new nuke," look at how it moves. Is it a cruise missile? A ballistic missile? That tells you what the country is actually afraid of.

Understand the "Third Offset." We are entering an era where AI and sensors might be able to find those "hidden" submarines. If that happens, the whole list of nuclear missiles becomes obsolete because the "invulnerable" leg of the triad isn't invulnerable anymore. This is why countries are rushing to build hypersonics—they need a new way to ensure they can still hit a target even if their old missiles are tracked.

The world of nuclear tech is moving away from "bigger is better" and toward "faster and weirder." Whether it's a 50-year-old Minuteman or a brand-new Avangard, these machines are the most complex things humans have ever built for a purpose we all hope never actually happens. Keeping an eye on the hardware is the only way to understand the real stakes of the headlines you see every day.