You’re reaching for a coffee mug on the top shelf and suddenly—snap. Not a literal snap, hopefully, but that sharp, biting twinge in the front of your arm that makes you drop the cup. Most people immediately rub the top of their shoulder and assume they’ve pulled a "shoulder muscle." But if you actually look at a detailed diagram of muscles in shoulder anatomy, you’ll realize that the "shoulder" isn't just one thing. It's a chaotic, beautiful, and incredibly fragile intersection of tendons and meat. Honestly, it’s a miracle we can throw a baseball or even put on a t-shirt without everything falling apart.

The human shoulder is the most mobile joint in the body. That’s the problem. To get that 360-degree range of motion, we sacrificed stability. Unlike the hip, which is a deep ball-and-socket tucked firmly into the pelvis, the shoulder is more like a golf ball sitting on a tiny tee. It stays there because of a complex web of muscles. If one of those muscles decides to quit, the whole system goes haywire.

The Rotator Cuff: More Than Just a Sports Injury

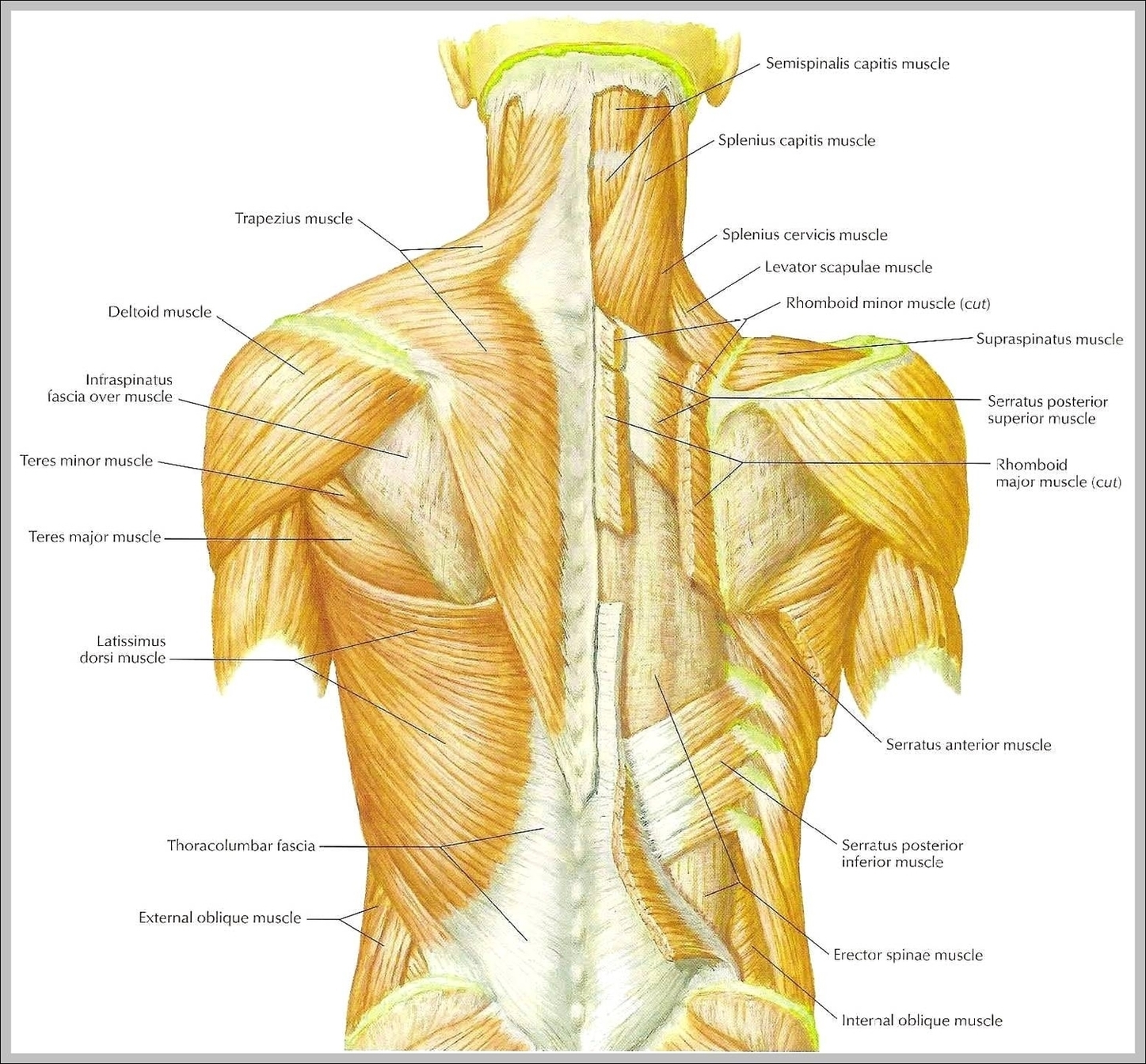

Everyone talks about the rotator cuff like it’s a single band of fabric. It’s not. When you see a diagram of muscles in shoulder layers, the rotator cuff is actually a group of four distinct muscles: the Supraspinatus, Infraspinatus, Teres Minor, and Subscapularis. Doctors and PTs often use the acronym SITS to remember them.

The Supraspinatus is the one that gets all the bad press. It sits right on top. Because it lives in a narrow bony tunnel called the subacromial space, it’s prone to getting pinched. This is what we call impingement. Imagine a garden hose getting stepped on; that’s your Supraspinatus every time you lift your arm if your mechanics are off.

Then you’ve got the Infraspinatus and the Teres Minor. These guys live on the back of your shoulder blade. Their entire job is external rotation. If you’ve ever seen someone at the gym doing those "waving" motions with a light cable, they’re targeting these. They are tiny but mighty. Without them, your shoulder would just roll forward into your chest, giving you that "caveman" posture we all get from staring at iPhones for eight hours a day.

The Hidden Muscle: Subscapularis

Most diagrams of shoulder muscles show the front and the back, but the Subscapularis is the "hidden" member of the cuff. It’s tucked underneath the shoulder blade, sandwiched between the bone and your ribs. You can’t really touch it from the outside. But it is the strongest of the four. It handles internal rotation. When it gets tight, it pulls the head of your humerus (arm bone) forward, which leads to that nagging ache in the very front of the joint that never seems to go away with a massage.

The Big Movers: Deltoids and Beyond

If the rotator cuff is the "steering" crew, the Deltoids are the engine. These are the muscles that give the shoulder its rounded shape. In any standard diagram of muscles in shoulder views, the deltoid is split into three heads: anterior (front), lateral (side), and posterior (back).

Most of us have overdeveloped anterior delts. Why? Because everything we do is in front of us. Typing. Driving. Cooking. Bench pressing. This creates a massive imbalance. A well-functioning shoulder requires the posterior deltoid to be strong enough to pull the shoulder back, but for most people, the back of the shoulder is as weak as a wet noodle.

Then we have the Trapezius and the Latissimus Dorsi. You might think of the "Lats" as back muscles, and they are, but they actually attach to the humerus. This means your big back muscles have a direct say in how your shoulder moves. If your lats are tight, you literally cannot lift your arm straight up over your head without arching your back. Try it. Stand against a wall and try to touch your thumbs to the wall above you without your lower back popping off. Hard, right? That’s because your shoulder anatomy is linked to your entire torso.

Why "Standard" Diagrams Can Be Misleading

If you pull up a basic diagram of muscles in shoulder on a search engine, it usually shows a static, muscular man in an anatomical position. Everything looks neat. In reality, muscles overlap like shingles on a roof.

Take the Biceps Brachii. Most people think of the biceps as an "arm" muscle. But the long head of the biceps tendon actually travels inside the shoulder joint and attaches to the top of the socket (the labrum). This is why people with "shoulder pain" often actually have bicep tendonitis. The pain radiates down the arm, but the source is deep inside the shoulder capsule.

Furthermore, the Serratus Anterior—often called the "boxer's muscle"—is frequently left out of basic diagrams. It looks like fingers gripping your ribs. Its job is to keep your shoulder blade (scapula) glued to your ribcage. If the Serratus is weak, your shoulder blade "wings" out. This ruins the foundation for every other shoulder muscle. You can’t fire a cannon from a canoe; if your scapula isn't stable, your rotator cuff has to work twice as hard, leading to those "mystery" tears that happen when you’re just doing something simple like putting on a seatbelt.

The Role of the Scapula

You can't talk about shoulder muscles without talking about the scapula. It’s the platform. Muscles like the Rhomboids and Levator Scapulae control how this platform moves. If you’re stressed, your Levator Scapulae hitches your shoulders up to your ears. Do that for three weeks straight at a desk job, and you’ll develop "trigger points" that feel like hard knots. These knots can actually mimic shoulder injuries by referred pain. It’s all connected.

Real-World Consequences: When the Diagram Fails

What happens when these muscles stop talking to each other? Usually, it's a slow burn.

- Adhesive Capsulitis (Frozen Shoulder): This isn't just a muscle issue; it's the connective tissue getting inflamed and thickening. However, the muscles around it will atrophy (waste away) because you stop moving the arm.

- Bursitis: There are little fluid-filled sacs called bursae that act as cushions between the muscles and bones. If your diagram of muscles in shoulder alignment is off—meaning the humerus isn't centered—it squishes these sacs. Inflammation city.

- Labral Tears: Since the biceps tendon attaches here, a sudden jerk can peel the labrum away from the bone. This feels like a "clunking" or "catching" sensation.

Dr. Kevin Wilk, a renowned physical therapist who has worked with athletes like Derek Jeter, often emphasizes that shoulder health is about "dynamic stability." It’s not about how much you can overhead press. It’s about whether those four tiny SITS muscles can keep the ball centered while the big deltoids are doing the heavy lifting.

Practical Steps to Fix Your Shoulder Mechanics

You don't need a medical degree to start fixing things. Honestly, most minor shoulder issues respond incredibly well to basic maintenance.

Stop focusing on the front.

If you spend 20 minutes doing chest presses, spend 40 minutes doing "pulling" exercises. Face pulls, rows, and "Y-W-T" raises are your best friends. These target the posterior deltoid and the lower traps, which are the muscles that actually keep your shoulder in its socket.

Release the Pecs.

Your Pectoralis Minor is a tiny muscle under your main chest muscle. When it gets tight, it tilts the shoulder blade forward and down. This closes the gap where the Supraspinatus lives. Use a lacrosse ball or a tennis ball against a wall to massage the area just below your collarbone. It’ll hurt, but it opens up the joint space.

The "Bottom-Up" Kettlebell Hold.

This is a "cheat code" for shoulder stability. Hold a light kettlebell upside down (handle in hand, heavy part pointing at the ceiling). Walk around. Your brain will automatically fire all those tiny stabilizer muscles in the rotator cuff just to keep the weight from flopping over. It’s "reprogramming" the muscles to work together without you having to think about a diagram of muscles in shoulder anatomy.

Check your thoracic mobility.

If your mid-back is stiff as a board, your shoulders have to compensate. Spend five minutes a day rolling out your upper back on a foam roller. If your spine can't move, your shoulders shouldn't be expected to either.

The reality is that shoulder health is a long game. We live in a world designed to make our shoulders roll forward and get weak. Understanding the layout—the way the deltoid protects the cuff, and the way the scapula provides the base—is the first step toward not being the person who "snaps" their shoulder while reaching for a cup of coffee. Treat the small muscles with as much respect as the big ones, and your joints will probably last a lot longer than the average desk-dweller's.