Bacteria get a bad rap. We think of strep throat, spoiled milk, or the plague. But if you actually look at a diagram of a bacteria cell, you aren't just looking at a germ. You're looking at the most successful biological design in the history of the universe. These tiny, single-celled organisms have been running the show for roughly 3.5 billion years. They were here before the dinosaurs, and they’ll be here long after we’ve figured out how to go extinct.

It's wild.

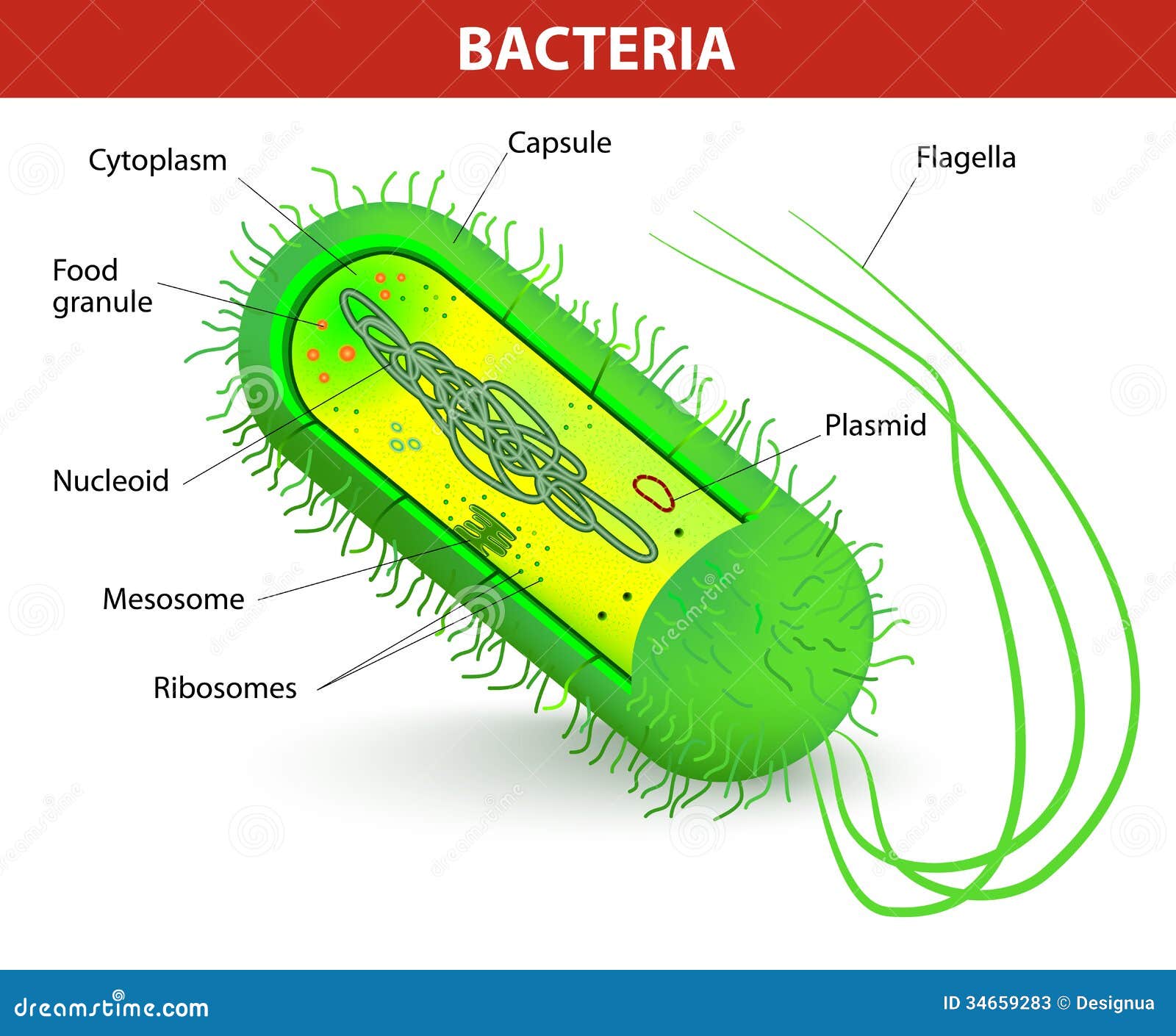

Most of us remember the basic drawing from ninth grade: a pill-shaped blob with a tail. But that's a massive oversimplification. Real bacteria are messy. They’re crowded. They’re basically chemical factories packed into a space so small you could fit a thousand of them on the tip of a needle. When you look at a professional diagram of a bacteria cell, you're seeing the blueprint for life at its most efficient.

The Protective Layers: More Than Just a Skin

Bacteria are tough. They have to be. They live in boiling vents, Antarctic ice, and your stomach acid. To survive that, they use a multi-layered defense system.

First, there’s the capsule. Not every bacterium has one, but the ones that do are usually the troublemakers. It’s this slimy, sugary coating—scientists call it a glycocalyx—that acts like a cloaking device. It helps the cell stick to surfaces (like your teeth) and hides it from your immune system. If a bacterium has a thick capsule, your white blood cells might just slide right off it.

Underneath that is the cell wall. This is the structural backbone. If you've ever heard of Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacteria, this is where that distinction happens. Gram-positive bacteria have a thick layer of peptidoglycan, a mesh-like polymer of sugars and amino acids. Gram-negative ones have a thinner layer but an extra outer membrane. This isn't just trivia; it's the reason why some antibiotics work on your ear infection and others don't. Penicillin, for instance, works by sabotaging the construction of that peptidoglycan wall.

Then you have the plasma membrane. It’s the gatekeeper. It decides what gets in (nutrients) and what stays out (toxins). It's a phospholipid bilayer, just like the ones in our cells, but bacteria use it for something way more impressive: energy production. Since they don't have mitochondria (the "powerhouse" we all learned about), they have to generate their ATP right there on the cell membrane.

The Inside Is Where the Magic Happens

Once you get past the walls, you’re in the cytoplasm. It’s a jelly-like substance, but don't think of it as empty space. It’s packed. It's so crowded with proteins and molecules that it behaves more like a glass or a gel than a liquid.

💡 You might also like: Children’s Hospital London Ontario: What Every Parent Actually Needs to Know

The Nucleoid and Plasmids

Bacteria are prokaryotes. That basically means they don’t have a nucleus. Instead of a neat little ball holding the DNA, they have a nucleoid. This is just a tangled, circular loop of DNA floating freely. It contains all the "essential" instructions for being a bacteria.

But here is the cool part: plasmids.

Plasmids are tiny, extra circles of DNA that exist outside the main loop. Think of them like "DLC" for a video game. They aren't necessary for life, but they provide "superpowers." One plasmid might give the bacteria the ability to resist an antibiotic. Another might allow it to digest oil. Bacteria can actually swap these plasmids with each other in a process called conjugation. It’s basically bacterial sex, and it’s how antibiotic resistance spreads through a hospital like wildfire.

Ribosomes: The Protein Factories

Scattered throughout that cytoplasm are thousands of ribosomes. They are smaller than the ones in human cells (70S vs. 80S), which is a massive win for medicine. Because they are different shapes, we can design drugs that gum up bacterial ribosomes without touching ours. That’s how many common antibiotics work—they effectively starve the bacteria of the proteins they need to function.

Moving and Shaking: Flagella and Pili

Look at any diagram of a bacteria cell and you’ll likely see a long, whip-like tail called a flagellum. It’s not just a floppy string. It’s one of the most incredible motors in nature. It’s powered by a proton gradient and can rotate at speeds of up to 100,000 RPM. If a bacterium were the size of a car, it would be going hundreds of miles per hour.

Then there are the pili (or fimbriae). These look like tiny hairs sticking out everywhere. They aren't for swimming. They’re for sticking. They act like grappling hooks, allowing the bacteria to latch onto host tissues. Some special pili, called sex pili, are used specifically to pull another bacterium close so they can trade those plasmids we talked about.

Why the Structure Actually Matters to You

Honestly, understanding this anatomy isn't just for passing a biology quiz. It’s about survival. Every part of that cell is a target for modern medicine.

📖 Related: Understanding MoDi Twins: What Happens With Two Sacs and One Placenta

Take the cell wall again. When you take an antibiotic like Vancomycin, it’s specifically targeting the cross-linking of the peptidoglycan. Without that wall, the internal pressure of the bacteria (which is quite high) causes the whole thing to literally explode.

Or consider the cytoplasmic membrane. Some newer "last-resort" antibiotics like Daptomycin work by poking holes in that membrane. It causes the cell’s ions to leak out, which is like draining the battery of a smartphone. The cell can't maintain its electrical charge and dies instantly.

The Nuance: Not All Diagrams Are Equal

When you're looking at a diagram of a bacteria cell, you're usually looking at a "composite" image. In reality, bacteria come in three main shapes:

- Cocci: Spherical (like the ones that cause pneumonia).

- Bacilli: Rod-shaped (like E. coli).

- Spirilla: Spiral-shaped (like the ones that cause Lyme disease).

A rod-shaped E. coli looks nothing like a spiral-shaped Syphilis bacterium under a microscope. Some have dozens of flagella; some have none. Some form spores—hardened, dormant versions of themselves that can survive being blasted into space or sitting in a desert for decades. This diversity is why bacteria are so hard to kill. They are masters of adaptation.

Common Misconceptions About Bacterial Anatomy

People often think bacteria are "primitive." That's a mistake. Complex doesn't always mean better.

While our cells (eukaryotes) are like massive, lumbering luxury liners with specialized rooms for everything, bacteria are like high-speed racing drones. They've stripped away the fluff. By having their DNA floating right next to their ribosomes, they can start building proteins almost the second they detect a change in their environment. We can't do that. Our DNA is locked in a vault (the nucleus), and the instructions have to be copied and shipped out before anything happens.

Speed is the bacterium's greatest weapon. Some species, like Vibrio natriegens, can double their population in less than 10 minutes.

👉 See also: Necrophilia and Porn with the Dead: The Dark Reality of Post-Mortem Taboos

Actionable Insights for Students and Health Geeks

If you’re studying a diagram of a bacteria cell or just trying to understand how these things impact your health, here’s how to apply this knowledge:

1. Respect the "Course of Antibiotics"

When a doctor tells you to finish the whole bottle, they aren't joking. If you stop early, you leave behind the bacteria with the strongest capsules and the best plasmids. These survivors then multiply, and suddenly, you've bred a colony of "superbugs" in your own body that are much harder to kill the next time.

2. Watch the Sugar

Bacteria love the capsule-building materials. Biofilms—those slimy layers of bacteria on your teeth or in your gut—thrive on simple sugars. By reducing sugar, you're literally making it harder for bacteria to build their protective "housing" and stick to your tissues.

3. Understand Resistance

Keep in mind that the plasmid exchange is happening everywhere—in the soil, in livestock, and in your sink. Using antibacterial soap for every little thing actually encourages the bacteria to swap those resistance genes. Standard soap and water usually do the trick by physically sliding the bacteria off your skin rather than trying to attack their cell walls.

4. Use Better Visuals

If you're a student, don't just look at one diagram of a bacteria cell. Compare a Gram-positive diagram with a Gram-negative one. The differences in the cell wall are the most important part of microbiology when it comes to clinical medicine. If you can draw the difference between the two from memory, you're ahead of 90% of the class.

Bacteria are the invisible architects of our world. They make the oxygen we breathe, they digest the food in our guts, and occasionally, they try to kill us. Understanding the mechanical parts inside those tiny cells is the first step toward understanding how life on Earth actually works. It's not just a blob; it's a masterpiece of biological engineering.

Next Steps for Deeper Learning:

Investigate the specific differences between archaea and bacteria. While they look similar on a basic diagram, their cell membranes use entirely different chemistry, proving that nature found two completely different ways to build a "simple" cell. You might also want to look up "endosymbiotic theory" to see how a bacterium eventually became the mitochondria inside your own body.