If you’ve ever looked at the chaotic fluctuations of the stock market or listened to a news report about global energy prices, you’ve heard the term "barrel" thrown around like common currency. But if you actually went out and tried to buy a physical barrel of oil, you might be surprised by what shows up—or doesn't. A barrel of crude oil is 42 gallons. Forty-two.

It’s a weird number, right? Most of us are used to round numbers. Ten, fifty, a hundred. Even a standard beer keg in the U.S. is about 15.5 gallons, and those blue plastic drums you see at hardware stores usually hold 55 gallons. So, why on earth did the global oil industry settle on 42?

Honestly, the answer is a mix of 19th-century tax evasion, physical strength, and a bunch of tired guys in Pennsylvania who just wanted to go home.

The Pennsylvania Origins of the 42-Gallon Standard

Back in the 1860s, the oil boom was basically the Wild West. When the first wells were struck in Titusville, Pennsylvania, there was no infrastructure. No pipelines. No tanker trucks. No standardized shipping containers. People used whatever they had lying around to move the "black gold." We’re talking whiskey barrels, beer casks, salt crates, and even old molasses tubs.

It was a logistical nightmare.

Buyers were constantly complaining that they were getting ripped off because one "barrel" might be thirty gallons while another was fifty. By 1866, producers realized they needed a standard to keep the peace and ensure trade could actually function. They landed on 42 gallons.

Why 42? Because a 42-gallon wooden barrel filled with oil weighs about 300 pounds. That was the maximum weight a single man could reasonably manhandle, tilt, and roll onto a barge or a wagon without snapping his back or needing a massive team of horses. It was the sweet spot of efficiency.

In 1872, the Petroleum Producers Association officially adopted the 42-gallon standard. A few years later, the U.S. Geological Survey and the Bureau of Mines followed suit. Even though we haven't used actual wooden barrels to ship oil in over a century, the ghost of those Pennsylvania laborers lives on in every price ticker on Wall Street.

The 42-Gallon Barrel vs. The 55-Gallon Drum

This is where people get confused. If you walk onto a modern industrial site, you will see rows of steel drums. Those are almost always 55-gallon drums.

You’ve probably seen them in movies or at construction sites.

If you pour a "barrel" of oil into one of those drums, you’ll have 13 gallons of empty space at the top. This discrepancy exists because the 55-gallon drum was a later invention, popularized during World War II for shipping fuel to the front lines. It was more durable and held more volume, but the financial markets were already deeply wedded to the 42-gallon math.

So, today, we trade in 42-gallon units (the "bbl"), but we often store or move smaller quantities in 55-gallon containers. It’s a bit like how we still use "horsepower" to describe electric cars that have never been near a stable.

What Actually Comes Out of a 42-Gallon Barrel?

Here is the kicker: when you refine a barrel of crude oil, you don't just get 42 gallons of gasoline. You actually get more than 42 gallons of finished products.

Wait. What?

It sounds like some kind of magic trick or a violation of the laws of physics, but it’s actually a process called processing gain. When crude oil is sent through a refinery, it’s heated and cracked into different components. Because the resulting products (like gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel) are less dense than the original heavy crude, they take up more volume.

On average, a 42-gallon barrel of crude produces about 44 to 45 gallons of refined products.

Breaking Down the Yield

Refineries are incredibly complex. They don't just "filter" the oil; they chemically transform it. Depending on whether the refinery is dealing with "Sweet Light" crude (like West Texas Intermediate) or "Sour Heavy" crude (like the stuff from Venezuela or parts of Canada), the output changes.

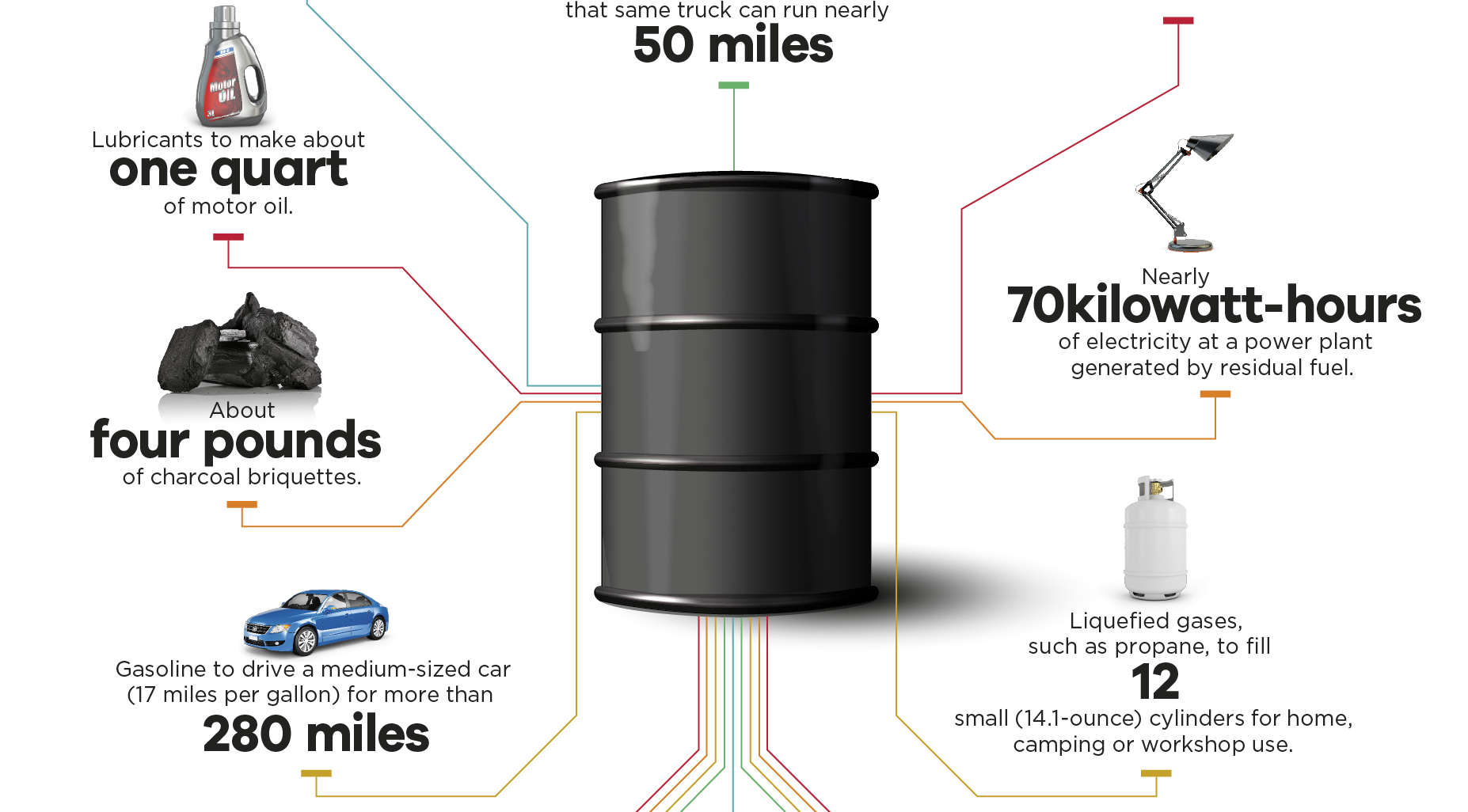

Generally, you can expect a single barrel to yield:

- Gasoline: Roughly 19 to 20 gallons. This is the big one. Almost half of every barrel goes toward keeping our cars moving.

- Ultra-Low Sulfur Diesel: About 11 to 12 gallons. This powers the trucks that deliver your Amazon packages and the trains that move freight across the country.

- Jet Fuel: Around 3 to 4 gallons.

- Other Products: The remaining 8 or 9 gallons are split between heating oil, heavy fuel oil (for massive cargo ships), and liquefied petroleum gases.

Then there are the byproducts. You know your polyester shirt? The asphalt on your driveway? The plastic casing on your smartphone? The toothbrush you used this morning? All of those come from the "leftovers" of that 42-gallon barrel. Even petroleum jelly—Vaseline—is a direct descendant of the gunk that rig workers in the 1800s found clogging up their pump joints.

📖 Related: Cooper Law White Plains: What Most People Get Wrong

Why the "bbl" Abbreviation?

If you look at oil market reports, you’ll see the abbreviation bbl for barrel. You might wonder why there are two "b"s. There is a popular legend that the second "b" stands for "Blue."

The story goes that Standard Oil, founded by John D. Rockefeller, used to paint their 42-gallon barrels blue to guarantee to customers that they were getting the full, honest amount. While it’s a cool story, and Standard Oil definitely used blue barrels, most historians think the "bbl" abbreviation predates Rockefeller. It was likely just a way to distinguish "barrels" from "bushels" or "bales," which were also common units of trade at the time.

Whatever the origin, if you see "bbl," just think "42 gallons."

The Impact of Gravity and "Sweetness"

Not all barrels are created equal. In the industry, we talk about API Gravity and Sulfur Content. If oil is "light," it has a high API gravity, meaning it’s thin and flows easily. If it’s "sweet," it has low sulfur content. This is the "prime rib" of the oil world. It’s easier and cheaper to turn into high-quality gasoline.

If the oil is "heavy" and "sour," it’s thick like molasses and smells like rotten eggs because of the sulfur. Refineries have to work much harder—and spend more money—to crack that 42-gallon barrel into something useful. This is why you’ll see different prices for West Texas Intermediate (WTI) versus Brent Blend or Western Canadian Select. You’re buying the same 42 gallons, but the potential inside those gallons is totally different.

Global Variations: The Metric Struggle

The United States is pretty much the last man standing when it comes to the 42-gallon barrel. Most of the rest of the world uses cubic meters or metric tonnes to measure oil.

This makes global trade math a headache.

📖 Related: Family Dollar Stores Inc Stock Price: What Most People Get Wrong

A metric tonne is a measure of weight, not volume. Because different types of oil have different densities, one metric tonne might contain anywhere from 6.5 to 8 barrels of oil. When a news outlet says "OPEC is cutting production by a million barrels," they are using the 42-gallon American standard because that remains the "lingua franca" of the global energy market.

Real-World Value: Beyond the Gas Pump

It’s easy to think of a barrel of oil as just "car juice," but its reach is honestly staggering. If a barrel of oil costs $80, that price ripples through the economy in ways that have nothing to do with your commute.

Think about a head of lettuce.

The tractor that plowed the field ran on diesel (from the barrel). The fertilizer used to grow the lettuce was likely made from natural gas or petroleum byproducts. The plastic wrap around the lettuce? Petroleum. The truck that drove it to the grocery store? Diesel. The refrigerated case it sits in? Powered by a grid that, in many places, still relies on oil or gas for peak loads.

When that 42-gallon unit gets more expensive, the salad gets more expensive.

Actionable Insights: What This Means for You

Understanding the "42-gallon" math helps demystify the energy sector. If you’re looking to apply this knowledge, keep these points in mind:

- Watch the "Crack Spread": If you’re an investor, don't just look at the price of crude. Look at the "crack spread"—the difference between the price of a 42-gallon barrel of oil and the price of the products refined from it. That’s where the real profit (or loss) for energy companies lives.

- Calculate Your Footprint: If you want to know how much raw crude you "consume," look at your annual mileage. If your car gets 25 mpg and you drive 12,500 miles a year, you’re using 500 gallons of gas. That requires roughly 25 to 26 full barrels of crude oil just for your driving, not counting the plastics and products you buy.

- Efficiency Matters: Because a barrel is a fixed 42-gallon unit, the only way for the world to "stretch" its oil supply is through refinery efficiency (getting more than 45 gallons of product out) or engine efficiency (getting more miles out of each gallon).

- Note the Packaging: Don't buy a 55-gallon drum thinking it's a "standard barrel" for pricing purposes. You are getting 13 extra gallons. If you're buying lubricants or chemicals for a business, always clarify if the quote is per drum or per 42-gallon industrial barrel.

The 42-gallon barrel is a relic of a time when men rolled wooden casks onto horse-drawn wagons. It’s clunky, it’s an odd number, and it doesn't match modern storage containers. Yet, it remains the heartbeat of global trade. Whether we like it or not, our entire modern lifestyle is built on the math of those 42 gallons.

Next time you see the price of oil flash on a screen, you’ll know exactly what you’re looking at: 300 pounds of history.