Look at him. Honestly, just look at him. If you close your eyes and think of a video game, you probably see those blocky red overalls and that brown mustache. It’s wild. We are talking about a character made of 256 tiny squares of color, yet 8 bit mario pixel art is arguably the most recognizable visual icon of the 20th century. Maybe even the 21st. It beats out Mickey Mouse in some demographics.

But here’s the thing people forget: Mario didn't look like that because Shigeru Miyamoto thought "low-res" was a cool aesthetic. He looked like that because he had to. The hardware was garbage by today's standards. Total garbage. Designers were fighting for every single pixel, and that struggle created a masterpiece of visual shorthand.

The 16x16 Reality Check

In the mid-80s, the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) was a beast compared to the Atari, but it was still basically a calculator with a dream. To make a character move across the screen without crashing the system, designers used "sprites." Mario was a 16x16 pixel sprite.

Think about that. 16 dots across. 16 dots down.

If you wanted to give him a mouth, you’d lose a pixel for the nose. If you gave him hair, you couldn't fit a hat. Miyamoto and his team, specifically folks like Takashi Tezuka, had to play a high-stakes game of digital Tetris just to make a human shape. This is why Mario has a mustache. It wasn't a fashion choice; it was a way to separate his nose from his face without needing to draw a mouth line. It’s brilliant. Truly. They gave him a hat because drawing realistic hair that actually moved when he jumped was technically impossible at the time. The "jumpsuit" or overalls? Those were there so you could see his arms move against his body. If he wore a solid-colored shirt, his arms would just disappear into his torso every time he ran.

Why 8 bit mario pixel art Still Feels "Right"

Ever notice how modern "retro" games sometimes feel... off? It’s usually because they have too many colors. The original 8 bit mario pixel art was limited by the NES color palette. The system could only show about 25 colors on screen at once, and each sprite was limited to just three colors (plus transparency).

Mario’s iconic look—red, brown, and a sort of peach/beige skin tone—was a direct result of this three-color cap.

Later on, in Super Mario Bros. 3, they added a black outline to help him pop against more complex backgrounds. That’s a huge shift. If you look at the 1985 Mario versus the 1988/1990 Mario, the evolution of pixel economy is staggering. They learned how to use negative space. They learned that a single pixel of a different shade could imply a shadow, making a flat image look 3D.

It's about abstraction. Your brain does half the work. When you see those few brown pixels for a foot, you don't see a square; you see a work boot hitting a Goomba. That's the magic of the medium. It’s impressionism for the digital age.

The Technical Wizardry of Palette Swaps

Money was tight and memory was tighter. Nintendo couldn't afford to design a hundred different enemies. So, they cheated. But they cheated in a way that defined an entire genre.

Take the clouds and the bushes in the original Super Mario Bros. Look at them closely. Really closely. They are the exact same sprite. The only difference is the color. Green for the bushes, white for the clouds. This is called a palette swap, and it’s the cornerstone of 8 bit mario pixel art efficiency. By changing a few hex codes, the developers doubled their environmental assets without using an extra byte of storage.

This extended to Luigi, too. For years, Luigi was just "Green Mario." He wasn't the tall, lanky, nervous guy we know today. He was a literal carbon copy with a different color set. It’s funny how a technical limitation actually birthed one of the most famous sibling duos in history. If the NES had more memory, Luigi might have been a completely different character from the start, and we’d lose that "Green Stache" legacy.

Recreating the Magic: Grid Logic

If you're trying to make your own pixel art today, you've gotta understand the grid. Modern screens have millions of pixels, but to get that authentic 8-bit feel, you have to work "low and slow."

- Start with 16x16. Don't go bigger until you've mastered the small stuff.

- Limit your colors. Stick to three or four colors per character. It forces you to be creative with shapes.

- Focus on the silhouette. If you turn your character completely black, can you still tell it’s Mario? You should be able to see the hat brim and the belly.

- Dithering is your friend. This is a technique where you checkerboard two colors to create the illusion of a third color or a gradient. It was used extensively in the later NES era to make things look "metallic" or "shaded."

Honestly, most people fail at pixel art because they try to be too detailed. Pixel art is about what you leave out. It’s the art of the "implied" curve. There are no circles in 8-bit gaming, only clever arrangements of squares that trick your eyes into seeing a round nose or a curved shell.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Donkey Kong 2 Soundtrack Still Bothers Modern Composers (In a Good Way)

The Cultural Weight of a Square

We see 8 bit mario pixel art everywhere now. T-shirts. Coffee mugs. High-end gallery walls. Why?

Part of it is nostalgia, sure. But it's more than that. It’s a design language that everyone understands. It's like a digital alphabet. In a world of 4K textures and ray-tracing, there is something deeply comforting about a visual style that doesn't try to hide what it is. It's honest. It says, "I am a video game."

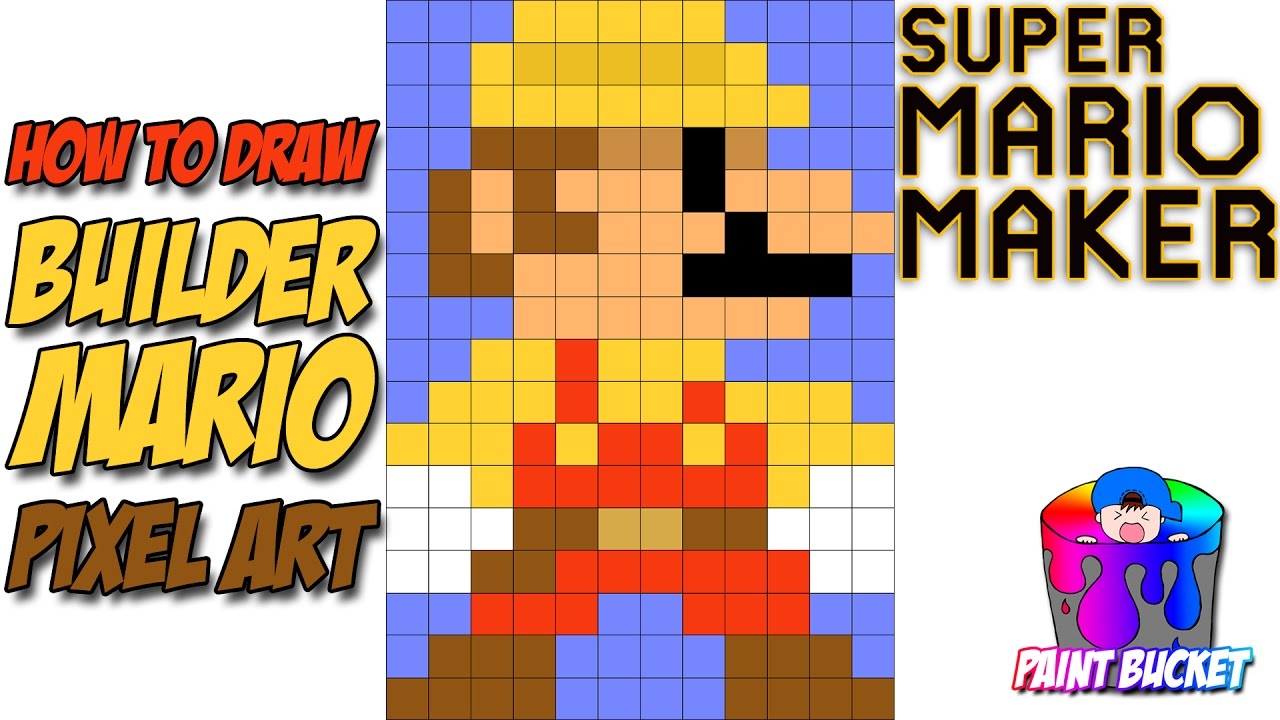

There's a reason Super Mario Maker became a global phenomenon. It gave people the keys to the kingdom. It let them manipulate those 16x16 blocks. When you place a block in a Mario level, you aren't just placing an asset; you're participating in a visual tradition that hasn't changed much since 1985.

Moving Forward With Your Own Designs

If you're looking to dive deeper into this world, stop looking at high-res tutorials. Go back to the source. Open a screenshot of the original Super Mario Bros. and zoom in until you can see the individual squares. Count them. See how a single pixel of white in the eye makes Mario look like he's looking forward.

Actionable Steps for Modern Creators:

- Use specialized software. Programs like Aseprite or even free tools like Piskel are built specifically for pixel art. They keep your edges "crunchy" and prevent the blurring that happens in Photoshop.

- Study the "Rule of Clusters." Good pixel art groups similar colors together to avoid "pixel noise." If your art looks messy, you probably have stray pixels floating around.

- Integer Scaling. When you export your 8 bit mario pixel art, always scale it by 100%, 200%, or 300%. If you scale it to a weird size like 150%, your pixels will look uneven and distorted.

- Practice limited palettes. Go to a site like Lospec and download an "NES Palette." Try to draw something using only those colors. It’s harder than it looks, but it’s the only way to truly understand why those old games looked the way they did.

Pixel art isn't just a "retro" phase. It's a fundamental pillar of digital design. Whether you’re a developer, an artist, or just someone who likes a bit of 80s flair, understanding the constraints of those early sprites is the best way to appreciate how far we’ve come—and how much we still owe to a tiny plumber made of squares.