Let's be real for a second. Most people looking up 500 degrees Celsius to Fahrenheit are usually either staring at a piece of industrial equipment, a high-end pizza oven, or perhaps a very concerning laboratory experiment. It's not a "room temperature" kind of number. It’s the kind of heat that changes how matter behaves.

If you just want the quick answer: 500°C is exactly 932°F.

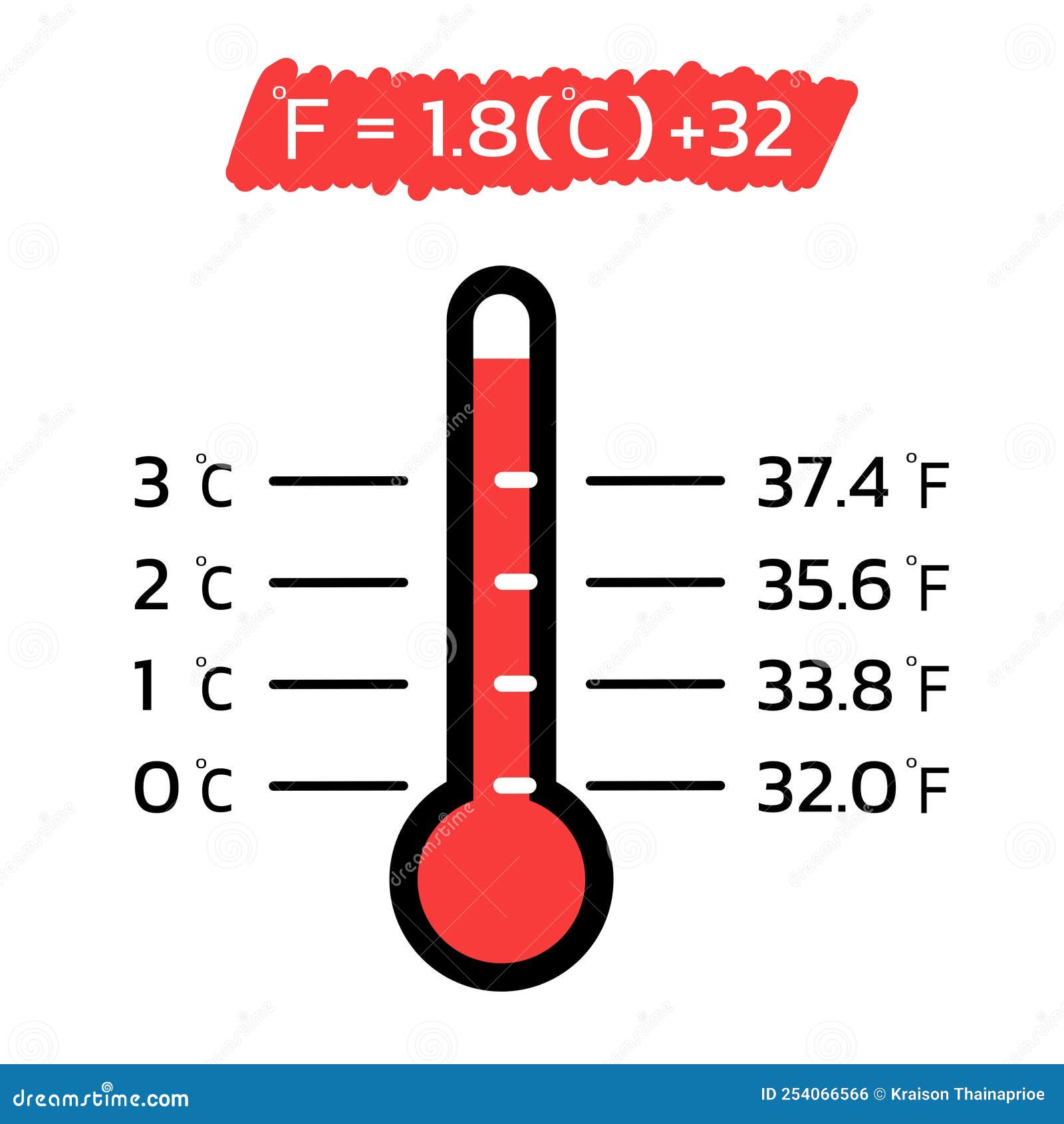

But why do we care? Honestly, the math is the boring part. You take the Celsius figure, multiply it by 1.8 (or 9/5 if you're feeling academic), and then add 32.

💡 You might also like: How Can I Listen to YouTube With Screen Off: Why It’s Still So Annoying and What Actually Works

$$500 \times 1.8 + 32 = 932$$

There. The calculation is done. But 932 degrees Fahrenheit is a weirdly specific threshold in the world of thermodynamics and materials science. It’s a "danger zone" for some metals and a "sweet spot" for others. When you hit this temperature, you aren't just dealing with "hot" anymore; you're dealing with the physical breakdown of common household materials.

The Chemistry of 500 Degrees Celsius to Fahrenheit

When we talk about 500 degrees Celsius to Fahrenheit, we are talking about a thermal energy level that is sufficient to trigger serious chemical transitions. Take wood, for instance. Wood doesn't just sit there at 500°C. It’s long gone. Most woods ignite at around 300°C. By the time you hit 500°C, you’re looking at the rapid decomposition of organic matter into carbon and volatile gases.

Think about lead. Lead melts at 327.5°C. So, at 500°C, lead isn't just a puddle; it’s a liquid that is actively seeking to reach its boiling point. If you were to dip a piece of steel into a vat of 500°C lead (which is a common industrial process called "lead patenting" used in wire manufacturing), the steel wouldn't melt, but its internal crystalline structure would start shifting.

Scientists like those at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) spend a lot of time looking at these high-temperature benchmarks. At 932°F, many aluminum alloys start losing their structural integrity. They don't melt—aluminum melts closer to 660°C—but they get "mushy." That’s a technical term. Well, sort of. In engineering, we call it a loss of tensile strength. If you’re building an engine or a fuselage, 500°C is often the point where you stop using aluminum and start looking at titanium or specialized nickel-based superalloys.

Why Your Pizza Oven Aims for 932°F

If you're a foodie, you've probably heard that a true Neapolitan pizza needs a blistering environment. This is where the conversion of 500 degrees Celsius to Fahrenheit becomes surprisingly relevant to your dinner.

The Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana (AVPN) actually sets standards for this. To get that "leopard spotting" on the crust—those tiny charred bubbles—without drying out the dough, the oven floor needs to be right around 430-480°C, with the air temperature often hitting that 500°C mark.

Why?

It's about the Leidenfrost effect and rapid evaporation. At 932°F, the moisture in the dough turns to steam so violently that it creates a cushion, allowing the crust to crisp up in 60 to 90 seconds. Any slower, and you're just making dry bread. Any hotter, and you're eating charcoal. It's a delicate balance.

Materials That Cry at 500°C

Let's get into the weeds of metallurgy. Most people assume "metal is strong," but heat is the great equalizer.

At 500 degrees Celsius to Fahrenheit, we encounter something called "creep." Creep is the tendency of a solid material to move slowly or deform permanently under the influence of persistent mechanical stresses. It happens more severely in materials that are subjected to heat for long periods.

- Glass: Most standard soda-lime glass (the stuff in your windows) starts to soften significantly well before 500°C. By 500°C, it's often at its "annealing point," where internal stresses are relieved, but it’s dangerously close to becoming a viscous fluid.

- Solder: Standard electronics solder is a distant memory by this point. It melted back at 180°C. If your computer hits 500°C, your motherboard is basically a graveyard of disconnected chips.

- Plastic: Don't even think about it. Even "high-heat" plastics like PEEK or PTFE (Teflon) have their limits. Teflon starts to outgas toxic fumes around 260°C and begins to physically degrade long before reaching 500°C.

The Practical Science of Conversion

While it’s easy to type 500 degrees Celsius to Fahrenheit into a search bar, understanding the ratio helps when you’re in the field without a phone. The Fahrenheit scale is more "granular" than Celsius. There are 180 degrees between the freezing and boiling points of water in Fahrenheit ($212 - 32 = 180$), but only 100 degrees in Celsius.

This means every 1 degree change in Celsius is a 1.8 degree change in Fahrenheit.

When you're dealing with 500°C, a small error in measurement—say, 10 degrees—actually means an 18-degree swing in Fahrenheit. In industrial ceramics or glassblowing, an 18-degree Fahrenheit error can be the difference between a perfect product and a shattered mess in the annealing kiln.

Extreme Environments and 500°C

Where do we actually find these temperatures naturally? Not many places on Earth's surface, thankfully.

- Volcanic Vents: Magma temperatures usually start around 700°C, but the surrounding rocks and gases often linger in that 500°C range.

- Venus: The surface of Venus is a constant, hellish 460-470°C. It’s almost exactly the threshold we're talking about. If you stood on Venus, you'd be experiencing a world that is nearly 900°F. Your lead boots would melt. Your electronics would fry instantly.

- Wildfire Crowns: In the middle of an intense forest fire, the "crown" (the tops of the trees) can hit temperatures exceeding 500°C. This is why wildfires are so hard to stop; the radiant heat is so high that it can ignite nearby fuel sources before the flames even touch them.

Safety and Measurement Tools

You cannot use a meat thermometer for this. Seriously.

If you're trying to measure 500 degrees Celsius to Fahrenheit in a real-world application, you need a K-type thermocouple or an infrared pyrometer. Standard liquid-in-glass thermometers (even the ones with mercury, which are becoming rare) usually top out around 350°C.

📖 Related: Why Does My Display Keep Turning Off? Let’s Actually Fix It

Infrared thermometers are great, but they have a "D:S" ratio (Distance to Spot). If you're standing too far away from a 500°C surface, the sensor averages the heat of the target with the cooler air around it, giving you a dangerously low reading. Always check the emissivity settings on your pyrometer; shiny metals at 500°C often look "cooler" to an IR sensor than they actually are because they reflect ambient radiation.

Actionable Next Steps for High-Heat Tasks

If you are working with temperatures in the 500°C / 932°F range, here is what you need to do to stay safe and accurate:

- Check your insulation: Ensure any wiring near the heat source is rated for "high-temp" use, typically involving fiberglass or ceramic braiding. Standard PVC insulation will melt and catch fire instantly.

- Verify with a Thermocouple: Use a digital multimeter with a K-type probe. It’s the industry standard for verifying that 500 degrees Celsius to Fahrenheit conversion in real-time.

- Thermal Expansion: Account for the fact that metals expand. A 1-meter steel bar will grow by about 6 millimeters when heated from room temperature to 500°C. That sounds small, but in a rigid structure, it will buckle the frame.

- Eye Protection: Use IR-rated safety glasses. At 932°F, materials begin to emit a faint dull red glow (the Blackbody radiation principle). This isn't just "light"; it’s infrared energy that can cause cataracts over long-term exposure.

Understanding 500°C isn't just about a math formula. It's about respecting the point where materials stop acting like themselves and start behaving according to the violent laws of high-energy physics. Whether you're baking a pizza or tempering steel, 932°F is a threshold that demands precision.