You’re looking at a box. It’s a cube, right? Solid, heavy, taking up space in your living room. But if you take a step back and really squint, you aren't seeing a cube at all. You're seeing a collection of squares joined at the edges. This is the fundamental weirdness of 2d shapes on 3d shapes. It’s the bridge between the flat world of a drawing and the chunky, physical world we actually live in.

Most people think of geometry as a dry subject from tenth grade. They remember formulas for area or volume and move on. But for architects, game designers, and even surgeons, the way a flat face sits on a three-dimensional body is everything. It’s the difference between a building that stands up and one that collapses under its own weight.

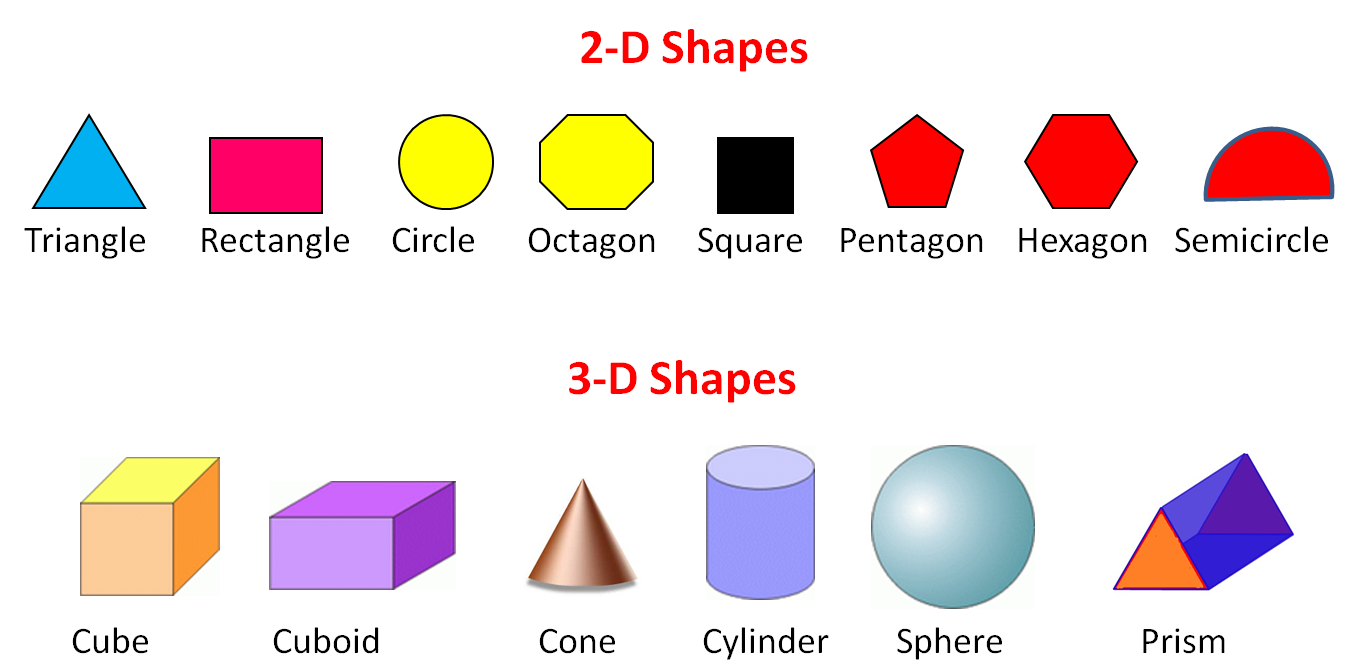

Let's get real. A 3D shape—what we call a solid—is basically just a prison for 2D shapes. If you take a standard D20 die from a tabletop game, you’re holding an icosahedron. But what your fingers are actually touching are twenty individual equilateral triangles. Those 2d shapes on 3d shapes are called "faces." Without the flat 2D surface, the 3D volume literally cannot exist in our mathematical reality.

The Geometry of the "Face"

Think about a cylinder. A Pringles can. It’s got two circles (2D) on the top and bottom. But what about the side? If you peel the label off that can, it isn't curved anymore. It’s a rectangle. This is where your brain starts to trip up. We perceive the curve as a 3D property, but the surface itself is a flattened 2D plane that has been "mapped" or wrapped around an axis.

In formal Euclidean geometry, we define these surfaces by their boundaries. A cube has six faces, and every single one is a square. A square is a 2D object. When you stack them, you get depth. But the moment you touch the surface of that cube, you are interacting with a 2D world.

Why Vertices and Edges Matter

You can't just slap 2d shapes on 3d shapes and call it a day. They have to meet. Where two faces meet, you get an edge (a 1D line). Where three or more edges meet, you get a vertex (a 0D point).

🔗 Read more: Big Drones in New Jersey: What Most People Get Wrong

Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler actually figured out a trick for this back in the 1700s. He found that for most solid shapes, if you take the number of faces, subtract the edges, and add the vertices, you always get two ($F - E + V = 2$). It’s a weirdly consistent rule of the universe. If you have a cube: 6 faces - 12 edges + 8 vertices = 2. It works for a pyramid too. It’s like the universe has a strict accounting department for how these shapes are allowed to hang out together.

Real-World Applications That Actually Matter

This isn't just for textbooks. If you’ve ever played a video game like Call of Duty or Fortnite, you are looking at millions of 2d shapes on 3d shapes every second.

Game engines use "polygons"—mostly triangles—to build characters. A character’s face might look smooth, but it’s actually a "mesh" of thousands of tiny flat triangles. Developers use a process called UV mapping. Imagine taking a 3D character and skinning it like a rug so it lies flat on a 2D plane. That’s how textures are painted. You paint on the 2D "net," and the computer wraps it back onto the 3D model. If the 2D shape doesn't align perfectly with the 3D volume, you get "texture stretching," which makes the character look like a melting candle.

Architecture operates on the same logic. Look at the Louvre Pyramid in Paris. It’s a massive 3D structure, but its entire aesthetic and structural integrity depend on the tessellation of glass triangles. Architect I.M. Pei had to calculate exactly how those 2D glass panes would meet at the joints to ensure the weight of the 3D structure didn't shatter the flat surfaces.

Common Misconceptions About Curvature

Here’s something that honestly trips people up: Is a sphere made of 2D shapes?

Technically, a sphere has one continuous surface. But in the world of manufacturing and digital design, we treat it as an infinite number of tiny flat planes. This is why a cheap soccer ball looks "blocky" if it doesn't have enough panels. To create a 3D curve from 2D materials (like leather or fabric), you have to use "gores"—those weird, eye-shaped strips used to make globes.

✨ Don't miss: What Most People Get Wrong About Hidden Apps on iPhone

You cannot flatten a sphere into a 2D shape without stretching or tearing it. This is "Theorema Egregium," a concept from Carl Friedrich Gauss. It’s why all flat maps of the Earth are technically "wrong." You're trying to force a 3D reality onto a 2D surface where it doesn't belong.

The Practical Side of Nets

In primary education, we use "nets." A net is the 2D skeleton of a 3D shape. If you’re a parent helping with homework, you’ve probably cut these out. A T-shape made of six squares folds into a cube. A circle with a wedge cut out folds into a cone.

But in the professional world, "nesting" is the high-stakes version of this. Companies that cut sheet metal or fabric use AI to fit as many 2D shapes (parts of a car or a suit) onto a flat sheet to minimize waste before they are welded or sewn into 3D objects. It saves billions of dollars. Literally.

How to Visualize This Better

If you want to master the relationship of 2d shapes on 3d shapes, stop looking at the whole object. Look at the "footprint."

- Shadows: A shadow is a 2D projection of a 3D object. A cylinder can cast a circular shadow or a rectangular one depending on the light.

- Cross-sections: If you slice a 3D shape, the "wound" is a 2D shape. Slice a cone horizontally? You get a circle. Slice it at an angle? You get an ellipse.

- Touch: Run your hand over a 3D object. Your palm, which is roughly flat, can only interface with the 2D facets of that object at any given moment.

Moving Forward: Your Geometric Toolkit

Understanding how these dimensions interact makes you better at everything from packing a trunk to DIY furniture assembly.

Identify the faces. Next time you see a complex object, like a hexagonal nut or a building, try to count the 2D shapes making up its exterior.

Watch for the transition. Look for where the "flat" becomes the "round." In manufacturing, this is often where the most stress occurs.

Experiment with unfolding. If you have an old cereal box, tear it open at the seams. Look at how the tabs (2D) allow the faces to lock into a 3D structure.

Geometry isn't just about math; it's about how the flat things we can draw become the real things we can hold. Once you see the 2D shapes hidden in the 3D world, you can't unsee them.

Take a look at the objects on your desk right now. Pick one up. Count the flat surfaces. Notice how many triangles, rectangles, or circles had to be "trapped" together to make that single object work. That’s the real power of spatial reasoning.