Tax law is a mess. Honestly, looking back at the 2019 federal tax brackets feels like staring at a time capsule from a very specific era of American fiscal policy. This was the second year the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) was in full swing. Everything had changed from the old days. If you’re digging through old records or trying to figure out an amended return, you’ve probably noticed that the numbers look a bit weird compared to today.

Inflation adjusted things, sure. But the core structure—the seven-bracket system—was the heavy hitter here.

Most people think they understand how taxes work. They don't. I’ve talked to so many folks who think that if they "move up" into a higher bracket, all their money gets taxed at that higher rate. That is 100% false. It’s a progressive system. Think of it like a series of buckets. You fill the 10% bucket first. Then the 12% bucket. Only the "overflow" goes into the next one. This is why your effective tax rate is always lower than your marginal tax rate.

The Seven Buckets of 2019

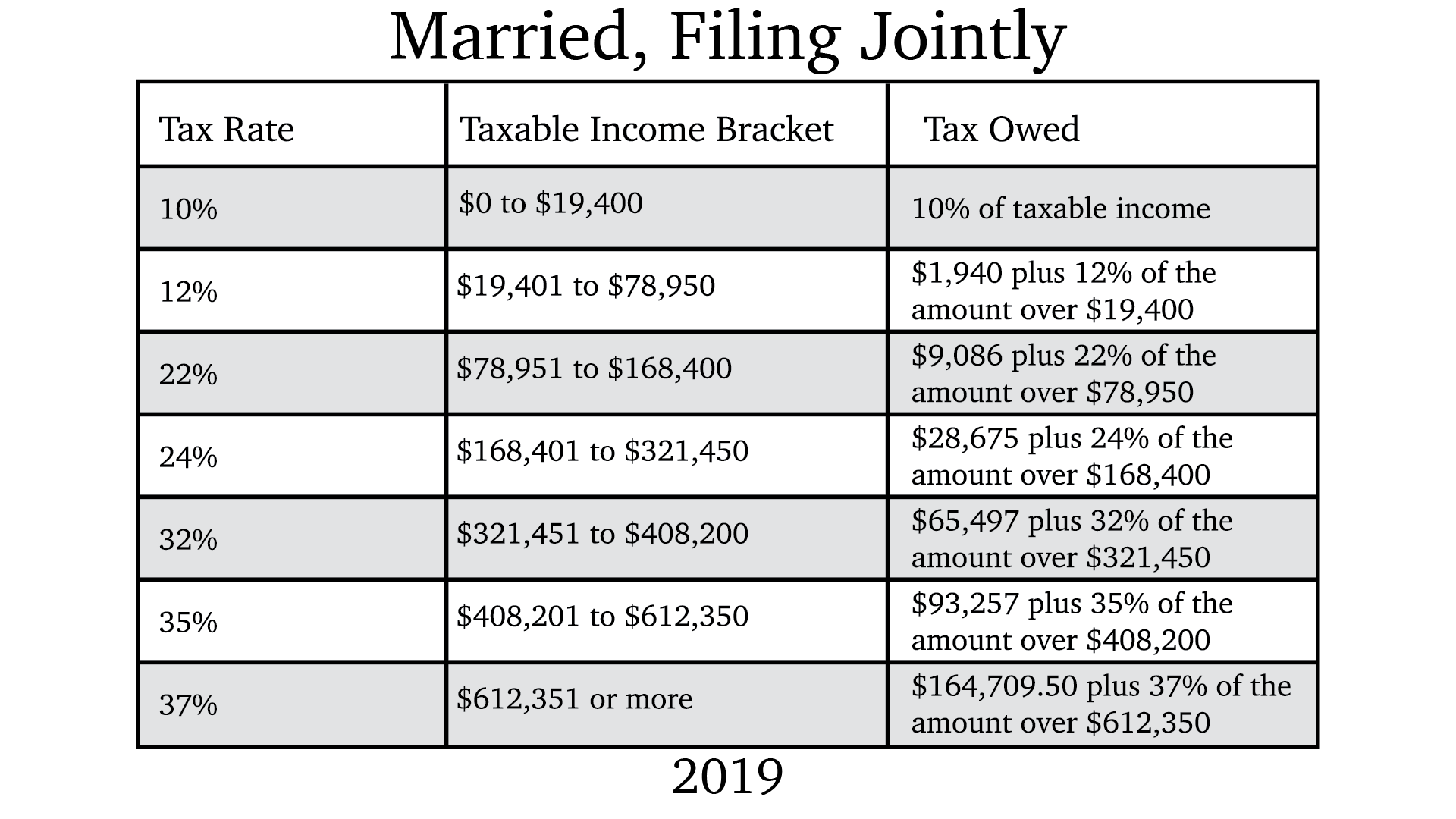

The IRS didn't just pull these numbers out of a hat. For the 2019 tax year, the rates were set at 10%, 12%, 22%, 24%, 32%, 35%, and 37%.

If you were a single filer, that 10% rate applied to your first $9,700 of taxable income. Once you hit $9,701, you weren't suddenly losing 12% of everything. You were only paying 12% on the dollars between $9,701 and $39,475. It’s a ladder. You climb it one rung at a time.

Married couples filing jointly had it a bit different. Their 10% bracket went all the way up to $19,400. Basically, the government doubled the "floor" for couples. But here is the kicker: the 2019 federal tax brackets had a "marriage penalty" at the very top. While most of the brackets for couples were exactly double the single rates, the 35% and 37% rungs didn't scale that way. For example, the top 37% rate kicked in at $510,300 for individuals but started at $612,350 for married couples. Not double. If you and your spouse were both high earners, you likely felt that squeeze.

Why the Standard Deduction Changed the Game

You can't talk about brackets without talking about the standard deduction. Before the TCJA, people obsessed over itemizing. They saved every receipt for charitable gifts and calculated their mortgage interest to the penny.

In 2019, the standard deduction jumped to $12,200 for singles and $24,400 for married filing jointly.

💡 You might also like: Loves Park Tax Service Options: What Most People Get Wrong About Local Filing

This meant that for a huge chunk of Americans, itemizing became pointless. If your total deductions didn't beat $12,200, you just took the flat "standard" amount. It simplified things for the IRS, but it also changed how people looked at their taxable income. Your "taxable income" isn't what you earned; it’s what you earned minus that deduction. So, if you made $50,000 as a single person in 2019, you weren't taxed on $50,000. You were taxed on $37,800. That’s a massive distinction that often gets lost in the noise.

Head of Household: The Middle Ground

There is this often-ignored category called "Head of Household." It’s for people who are unmarried but pay more than half the cost of keeping up a home for a qualifying person. In 2019, these folks got a better deal than singles but not quite the same cushion as married couples. Their 12% bracket went up to $52,850. It’s a sort of "buffer" for single parents or people supporting elderly relatives.

Real World Math: An Illustrative Example

Let's look at Sarah. She’s single. In 2019, she earned $60,000.

First, she takes the $12,200 standard deduction. Now her taxable income is $47,800.

She pays 10% on the first $9,700 ($970).

She pays 12% on the amount from $9,701 to $39,475 ($3,573).

Finally, she pays 22% on the remaining $8,325 ($1,831.50).

Total tax? $6,374.50.

Her marginal rate is 22%, but her effective rate—the actual percentage of her total income she paid—is only about 10.6%.

This is where people get tripped up. They see "22%" and panic. But as you can see, Sarah isn't actually losing a quarter of her paycheck to the feds.

The Sunset Clause You Need to Watch

Here is something nobody talks about enough. The 2019 federal tax brackets weren't permanent. They are part of a law that is scheduled to "sunset" after 2025.

If Congress doesn't act, we go back to the old rates. The 12% becomes 15%. The 22% becomes 25%. The standard deduction gets cut roughly in half. Looking back at 2019 isn't just a history lesson; it's a glimpse at a low-tax environment that might be disappearing soon. Experts like those at the Tax Foundation or the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities have been sounding the alarm on this for a while. We are currently living in a "discount" era of tax history.

Common Misconceptions About 2019 Credits

Brackets are only half the story. The 2019 tax year also saw the Child Tax Credit at $2,000 per qualifying child. This was a "refundable" credit up to $1,400.

A "credit" is way better than a "deduction." A deduction lowers the income you're taxed on. A credit is a straight-up dollar-for-dollar reduction of your tax bill. If Sarah owed $6,374 but had one kid, her bill dropped to $4,374. Simple.

Then there was the SALT deduction (State and Local Taxes). In 2019, this was capped at $10,000. For people in high-tax states like California or New York, this was a massive blow. Before 2018, you could deduct almost all your state taxes. In 2019, the brackets might have looked lower, but losing that deduction meant many middle-class families in blue states didn't actually see a huge "cut."

Nuance Matters: Capital Gains and Dividends

Don't confuse your 2019 federal tax brackets for ordinary income with your capital gains rates. They are different beasts.

If you sold stocks in 2019 that you held for more than a year, you weren't looking at those 12% or 22% numbers. Long-term capital gains had their own brackets: 0%, 15%, and 20%.

- 0% if your taxable income was under $39,375 (single).

- 15% if it was between $39,376 and $434,550.

- 20% if you were a high roller above that.

This is why wealthy people often pay a lower effective rate than doctors or lawyers. Their income comes from investments (taxed at 15% or 20%) rather than "labor" (taxed at up to 37%). It’s a quirk of the American system that became very pronounced under the 2019 rules.

What Should You Do Now?

If you're looking at 2019 data because you're behind on taxes, stop stalling. The IRS has a three-year window for claiming refunds. If you didn't file for 2019, you’ve likely passed the "statute of limitations" for a refund, but if you owe money, the interest is compounding.

- Gather your 2019 W-2s and 1099s. You can request a "Wage and Income Transcript" from the IRS website if you lost them.

- Check your filing status. Did you qualify for Head of Household? It could save you thousands compared to filing as Single.

- Look for missed credits. Did you qualify for the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)? For 2019, the maximum EITC was $6,557 for those with three or more children.

- Compare your 2019 "taxable income" to your total income. If the gap is exactly $12,200 (or $24,400 for couples), you took the standard deduction. If it's more, you likely itemized.

- Audit your withholding. If you owed a lot in 2019, look at your current W-4. The 2019 brackets were the "new normal," and if you haven't updated your withholding since the Obama era, you're probably doing it wrong.

The 2019 federal tax brackets were designed to put more money in the pockets of the average worker through lower rates and a higher standard deduction. While it worked for many, the complexity of the SALT cap and the "marriage penalty" at the high end made it a mixed bag for others. Understanding these nuances isn't just for accountants—it's how you make sure you aren't leaving money on the table when dealing with the IRS.