You’re standing in the kitchen, staring at a recipe from a European blog or a fancy UK cookbook, and there it is: 200 degrees celsius. You look at your American oven dial. It doesn’t go to 200. Well, it does, but that would barely melt butter.

So, 200 degrees celsius equals what in fahrenheit?

The short answer is 392°F.

But honestly, if you just turn your dial to 392, you’re probably going to have a bad time. Most ovens in the States calibrate in 25-degree increments. You’re choosing between 375°F and 400°F. Which one do you pick? If you go too low, your roast chicken won't get that "shatter-crisp" skin. Go too high, and your puff pastry might turn into a charred mess before the middle even thinks about cooking. It’s a delicate balance.

The Math Behind the Heat

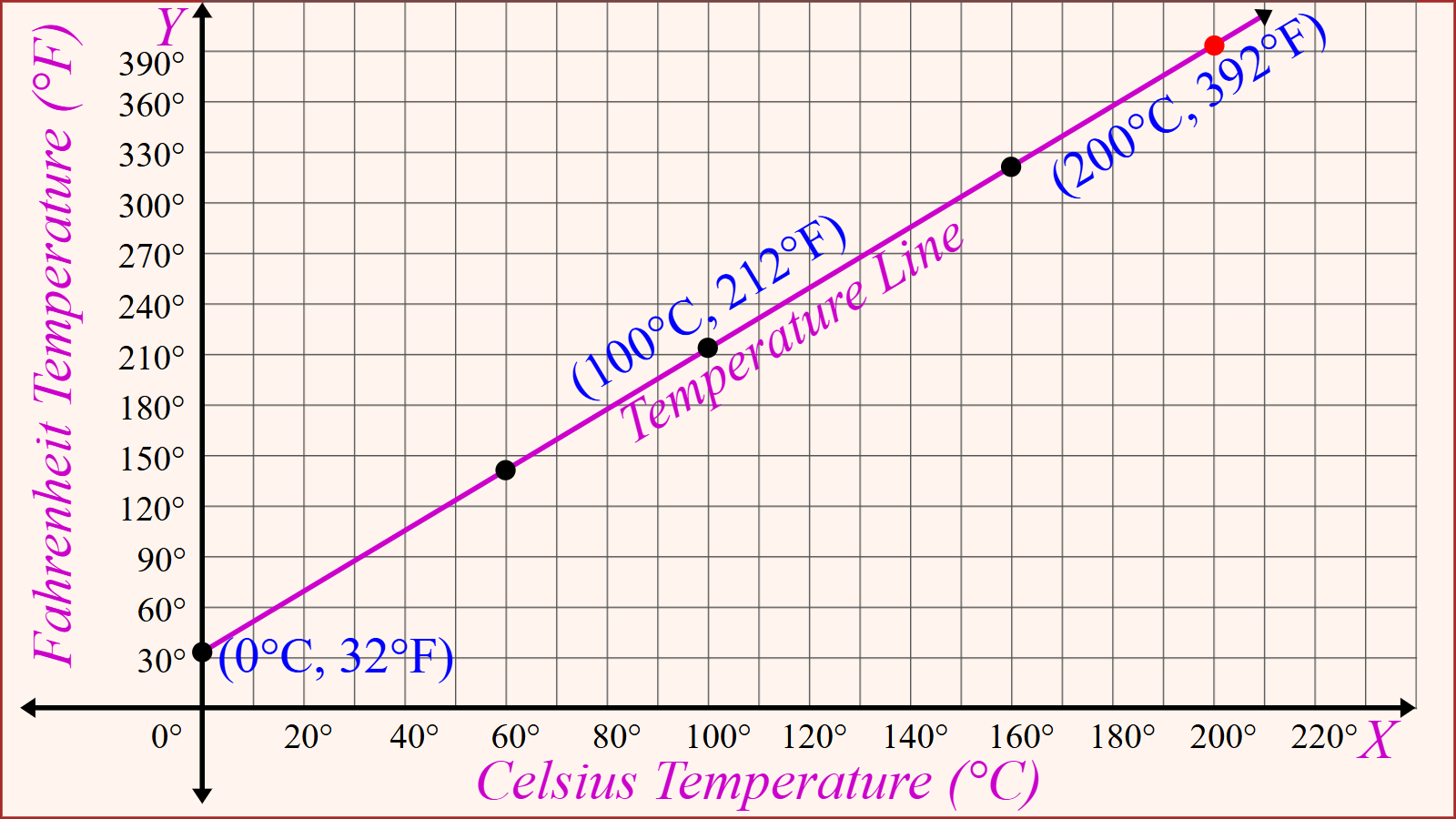

Let’s get the technical stuff out of the way. If you want to be precise—like, laboratory precise—you use a specific formula. You take the Celsius temperature, multiply it by 9, divide by 5, and then add 32.

Mathematically, it looks like this:

$$F = (C \times \frac{9}{5}) + 32$$

For our specific number:

$200 \times 1.8 = 360$.

$360 + 32 = 392$.

Simple? Kinda. But nobody wants to do long-form division while they’re trying to sear a steak or prep a Sunday roast.

The interesting thing about 200°C is that it’s a "threshold" temperature in the culinary world. It’s right on the edge. In France, they often refer to temperatures by "Thoms" or "Thermostat" numbers. 200°C is Gas Mark 6 or Thermostat 6/7. It represents a "hot" oven, but not a "very hot" oven. That distinction matters more than the three degrees between 392 and 395.

📖 Related: Charlie Gunn Lynnville Indiana: What Really Happened at the Family Restaurant

Why 392°F is the Magic Number for Maillard

Ever wonder why so many roasted vegetable recipes call for 200°C? It’s because of the Maillard reaction. This isn't just some science-fair term; it’s the reason food tastes good. It's the chemical reaction between amino acids and reducing sugars that gives browned food its distinctive flavor.

At 200°C (392°F), you are safely above the point where browning starts (usually around 140°C to 165°C), but you aren't yet at the point where things carbonize instantly.

If you’re roasting Brussels sprouts, 392°F is the sweet spot. It's hot enough to caramelize the outer leaves into salty, crispy chips while the core stays tender. If you dropped it to 350°F (about 175°C), the sprouts would just steam. They’d be gray. Sad. Nobody wants sad sprouts.

The Common "Rounding" Trap

Most people see 200 degrees celsius equals what in fahrenheit and they just round up to 400°F.

Is that okay? Usually.

But if you are baking something delicate—think macarons or a specific type of sponge cake—eight degrees is a lifetime. In a standard home oven, the temperature fluctuates anyway. Most ovens "cycle." They heat up to, say, 410°F, then shut off until they drop to 385°F, and then kick back on.

If you set your oven to 400°F because you were too lazy to aim for 392°F, your "peak" heat might actually be hitting 420°F. That's enough to cause a cake to rise too fast, crack across the top, and then collapse like a failed souffle.

Altitude and Air: The Variables Nobody Mentions

If you’re in Denver or somewhere high up in the Rockies, 200°C isn’t the same as 200°C in Miami.

Lower air pressure means water evaporates faster. If you’re following a British recipe at high altitude and you set your oven to 392°F, your food might dry out before it actually cooks through. High-altitude bakers often increase the temperature slightly but decrease the cooking time. It sounds counterintuitive, but you want to set the structure of the bake before the moisture all leaves the building.

👉 See also: Charcoal Gas Smoker Combo: Why Most Backyard Cooks Struggle to Choose

Then there’s the convection factor.

In the UK and Europe, "fan ovens" are the standard. If a recipe says "200°C Fan," that is actually equivalent to 220°C in a conventional oven.

Why? Because the fan moves the hot air around, stripping away the "cold air curtain" that naturally surrounds food. It cooks faster and more intensely.

So, if you see a recipe calling for 200°C Fan, you shouldn't be looking for 392°F. You should be looking for 425°F.

Real World Examples: What Lives at 200°C?

Let's look at some actual dishes that rely on this specific temperature.

- Roast Potatoes: To get that glass-like crunch on the outside of a Yukon Gold or a Maris Piper, 200°C is the gold standard.

- Puff Pastry: Whether it's beef wellington or a simple tart, you need the hit of 392°F to turn the water in the butter into steam instantly. That’s what creates the "lift" or the layers. If the oven is too cool, the butter just melts and leaks out, leaving you with a greasy puddle.

- Salmon Fillets: A high-heat roast at 200°C for about 10-12 minutes keeps the center fatty and moist while the top gets a slight crust.

Breaking Down the "Gas Mark" Confusion

If you’re looking at old vintage recipes, you might not even see degrees. You might see "Gas Mark."

| Celsius | Fahrenheit | Gas Mark | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 150°C | 300°F | 2 | Slow |

| 180°C | 350°F | 4 | Moderate |

| 200°C | 392°F | 6 | Hot |

| 220°C | 425°F | 7 | Very Hot |

Notice how 200°C is the jump into "Hot" territory. It’s the gateway temperature for roasting rather than just "baking."

How to Calibrate Your Kitchen

Don't trust your oven. Honestly.

I’ve lived in apartments where the dial said 400°F, but the internal temperature was barely hitting 360°F. If you’re obsessed with getting that 200°C (392°F) precision, buy a $10 oven thermometer. Hang it on the center rack.

✨ Don't miss: Celtic Knot Engagement Ring Explained: What Most People Get Wrong

You might find that to hit 392°F, you actually need to set your American oven to 415°F. Or maybe your oven runs hot and you only need to set it to 375°F.

The Science of Water and Heat

At 200°C, you are nearly double the boiling point of water. This is crucial for "oven spring" in bread. When dough hits a 200°C environment, the gases inside expand rapidly before the crust hardens. This gives you a light, airy loaf instead of a dense brick.

If you’re using a Dutch oven for sourdough, that 200°C–220°C range is where the magic happens. The steam trapped inside the pot keeps the surface of the dough supple, allowing it to expand fully under that intense 392°F heat.

Practical Steps for Your Next Meal

If you're staring at a recipe right now that demands 200°C, here is exactly what you should do to ensure you don't ruin dinner.

First, check if it's a fan recipe. If the recipe is from a UK source (like BBC Good Food), they almost always assume a fan oven. If you have a standard American oven without a fan, aim for 425°F.

Second, consider the "preheat" lie. Your oven will beep and say it’s ready in 10 minutes. It’s lying. The air might be 392°F, but the walls of the oven aren't. As soon as you open the door to put your food in, all that hot air rushes out, and the temp drops 50 degrees. Let your oven preheat for at least 20-30 minutes so the actual chassis of the unit is radiating heat.

Third, use the middle rack. Unless you're trying to burn the bottom of a pizza, the middle rack provides the most even distribution of that 392°F energy.

Fourth, trust your eyes, not just the clock. 200°C is a "fast" temperature. Things can go from perfect to burnt in a matter of two minutes. Start checking your food about 5-10 minutes before the timer is supposed to go off.

To get the most out of your cooking, stop thinking of temperatures as static numbers and start thinking of them as "heat intensity." 200°C (392°F) is high-intensity heat. It's for browning, crisping, and quick cooking. If you treat it with respect, your kitchen game will level up significantly.

Check your oven's actual internal temperature with an external thermometer this week. You might be surprised to find your "392°F" is actually something else entirely. Fixing that one discrepancy is the fastest way to stop "failing" at recipes that should be simple.