It is a weird middle child. Most homeowners look right past it. They see the 30-year fixed and think, "low payments, easy life." Or they eyeball the 15-year and tell themselves they’re going to be debt-free by 50. But 20 year mortgage rates often sit in this sweet spot that honestly makes a lot more sense for people who are actually looking at the math.

As of mid-January 2026, the national average for a 20-year fixed mortgage is hovering right around 5.94% to 6.03% APR.

Compare that to the 30-year, which is sticking near 6.13% to 6.20%. It’s not a massive gap on paper. A few basis points here, a tenth of a percent there. But you've got to look at the total interest. That's where the 20-year starts to look like a genius move.

The Math Behind the Middle Ground

Most people assume the 20-year rate is just a slightly higher 15-year rate. It's not. Lenders view it differently.

For a bank, a 20-year loan is less risky than a 30-year one because you're paying it back faster. However, because it's not the "industry standard" like the 30-year, some smaller banks don't even offer it. You’ll find it most often at places like Pennymac, Navy Federal, or Bank of America.

Let's look at a real-world scenario. Say you're borrowing $380,000.

If you take a 30-year at 6.14%, your monthly principal and interest is roughly $2,313.

Switch that to a 20-year at 5.93%, and your payment jumps to $2,707.

Yeah, it's about $400 more every single month. That’s a car payment. It's a lot of groceries. But here is the kicker: you shave a full decade off your debt. You also save over **$180,000 in total interest** over the life of the loan.

💡 You might also like: Xcel Energy Stock Price: Why Most People Get It Wrong Right Now

Why 2026 is Changing the Strategy

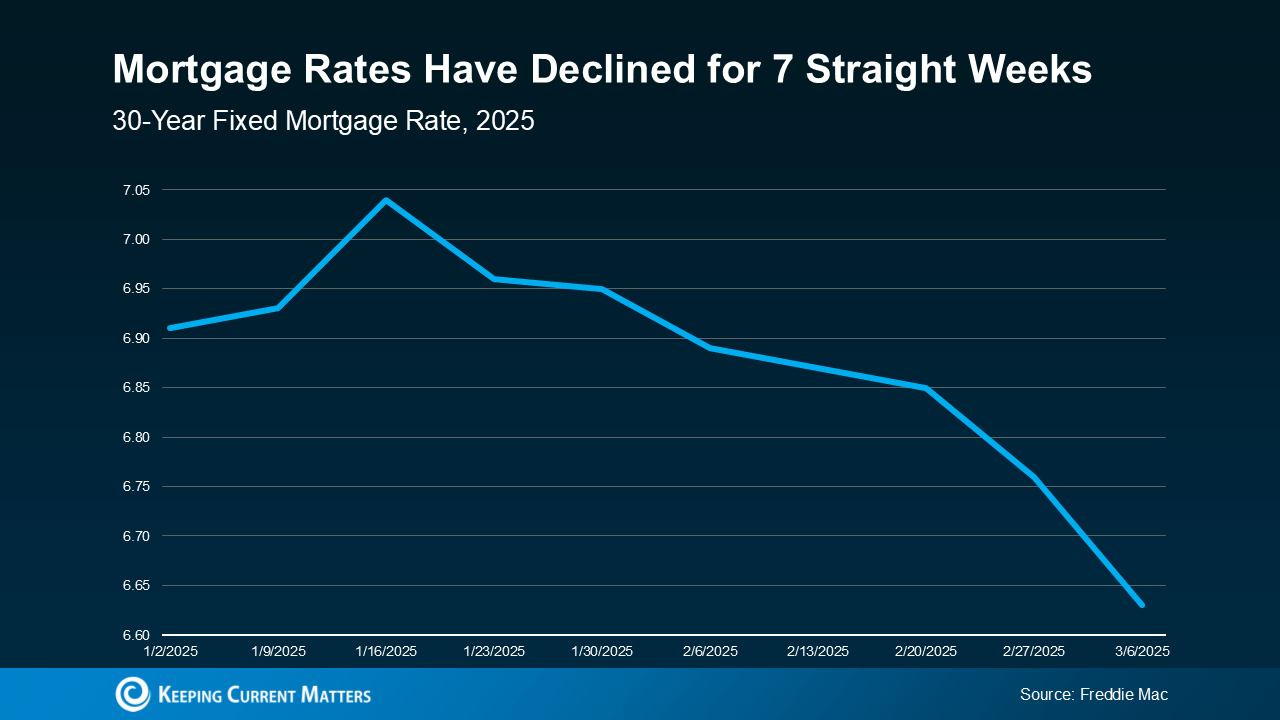

We are seeing a weird trend this year. According to recent data from Freddie Mac and analysts like Ted Rossman at Bankrate, the "lock-in effect" is finally starting to crack. People who bought when rates were at 7.5% or 8% in late 2023 and 2024 are looking to refinance.

They don't want to restart a 30-year clock.

If you’ve already paid three years into a 30-year mortgage, why would you sign up for another 30? Refinancing into a 20-year allows you to keep your original payoff date—or even move it up—while still snagging a lower rate than the current 30-year averages.

Who actually wins with a 20-year loan?

- The "Refi" Crowd: As mentioned, if you're 5 years into a 30-year, jumping to a 20-year feels natural.

- The Late Bloomers: If you're buying your first home at 45, a 30-year mortgage takes you well into your 70s. That’s not ideal for retirement. A 20-year gets that house paid off by 65.

- The High Earners: If your DTI (debt-to-income ratio) can handle the $400-$600 monthly increase, the 20-year is a guaranteed "investment" return because of the interest you aren't paying the bank.

The Downside Nobody Mentions

It’s not all sunshine. The 20-year has a trap.

Basically, you are committing to a higher payment. With a 30-year mortgage, you can always choose to pay it like a 20-year by sending extra principal every month. That gives you "budgetary flexibility." If you lose your job or have a medical emergency, you can drop back to the lower 30-year minimum payment.

With a 20-year mortgage, that higher payment is your required minimum. If things get tight, the bank doesn't care that you're trying to be fiscally responsible; they just want their $2,700.

Current Market Drivers

The Federal Reserve has been busy. After several cuts in late 2025, inflation has cooled enough that the 10-year Treasury yield—which mortgage rates tend to follow—is behaving better.

But there’s a lot of volatility.

Morgan Stanley strategists suggest we might see rates dip to 5.5% by mid-2026, but they expect them to climb again toward the end of the year. This makes the current window for 20 year mortgage rates pretty interesting. You aren't getting the 3% rates of the pandemic (those are gone, honestly, probably forever), but you are getting a much better deal than the "Great Rate Hike" of a few years ago.

Comparing the Options (Approximate January 2026 Averages)

- 15-Year Fixed: ~5.38% (Lowest rate, highest payment)

- 20-Year Fixed: ~5.97% (Middle ground, significant interest savings)

- 30-Year Fixed: ~6.16% (Most popular, lowest payment, highest total cost)

Is it right for you?

Don't just look at the rate. Look at your "burn rate."

If you have a solid emergency fund—we're talking 6 months of expenses—then the risk of the higher 20-year payment is minimal. But if you’re living paycheck to paycheck, even if the math says you save $100k in interest, the 30-year is the safer bet. You can always pay extra when you have it.

Also, check the "points." Right now, many advertised rates (like those from Pennymac) include "discount points." That means you’re paying cash upfront to get that 5.9% rate. If you aren't planning to stay in the house for at least 7 to 10 years, paying for points is usually a waste of money.

Actionable Next Steps

- Calculate your "Break-Even": Use a mortgage calculator to see the exact difference between a 30-year and 20-year payment for your specific loan amount. If the difference is less than 15% of your take-home pay, the 20-year is a strong contender.

- Get a "Plain" Quote: Ask lenders for a quote with zero points. It’s the only way to compare apples to apples.

- Check Credit Union Rates: Organizations like Navy Federal or local credit unions often have more aggressive pricing on 20-year terms than the "Big Three" banks because they hold the loans on their own books.

- Evaluate your Retirement Timeline: If you want to be debt-free by a specific age, work backward. If that age is 20 years away, the choice is made for you.

The 20-year mortgage isn't a gimmick; it’s a tool. It's for the person who hates debt more than they love monthly cash flow. In the current 2026 market, where rates are finally stabilizing, it might just be the smartest way to buy a home without giving the bank a second house's worth of interest.