Tax season usually feels like a slow-motion collision with a filing cabinet. You're digging through drawers, swearing you saw that 1099-INT last week, and trying to remember if that high-yield savings account actually cleared the threshold for a formal report. Honestly, most people dread the 1040 Schedule B instructions because they look deceptively simple until you’re staring at a foreign bank account question that feels like a trap.

It isn't just about listing a few dollars of interest. It's about the IRS making sure you aren't hiding a nest egg in the Cayman Islands or neglecting to report that "gift" from a brokerage account.

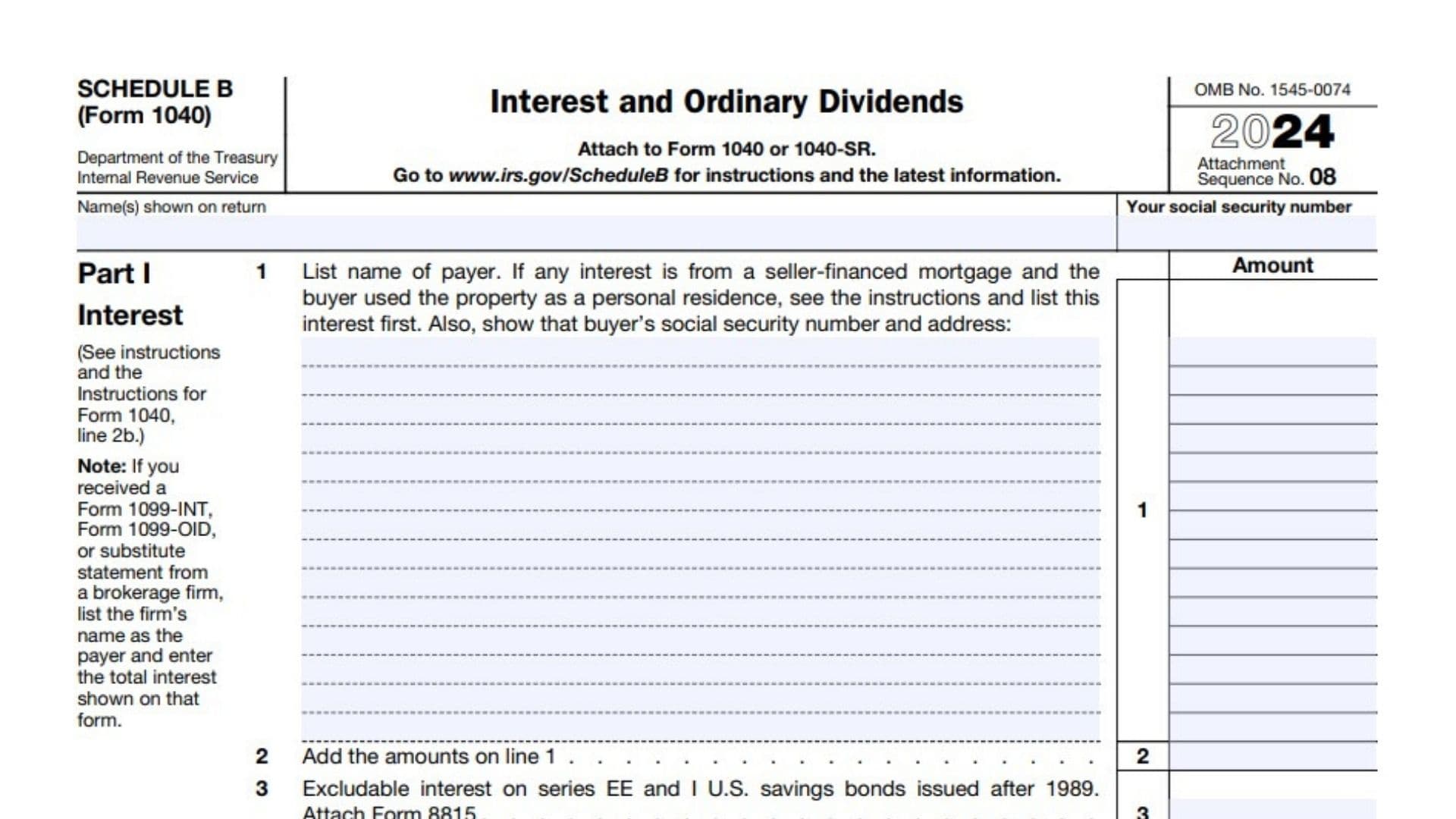

If you made more than $1,500 in taxable interest or ordinary dividends, you’re in Schedule B territory. That’s the magic number. Under that? You can usually just park the total on your Form 1040 and move on with your life. But once you cross that line, the IRS wants the granular details. They want to see exactly who paid you and exactly how much.

Why the $1,500 Rule Isn't the Only Trigger

You might think you're safe because your Ally bank account only spit out $1,200 this year. Not so fast. The 1040 Schedule B instructions actually list several "gotcha" scenarios where you have to file the form even if you didn't hit that dollar amount.

For instance, if you’re claiming the exclusion of interest from series EE or I U.S. savings bonds issued after 1989, you’re filing Schedule B. No exceptions. It’s the same story if you received interest as a nominee—meaning the money hit your account but actually belongs to someone else—or if you’re dealing with Accrued Interest Adjustment.

Then there’s the big one: Foreign accounts.

If you had a financial interest in or signature authority over a foreign bank account, brokerage account, or even certain foreign trusts, the IRS wants to know. Part III of Schedule B is basically a giant spotlight on your international ties. Even if your domestic interest was zero, having that foreign account often forces you into this form.

Breaking Down Part I: Interest is More Than Just Savings

Most people think Part I is just for their local credit union. It’s broader. You’re looking at taxable interest from bank accounts, money market accounts, certificates of deposit (CDs), and even corporate bonds.

But here is where it gets nuanced.

Seller-Financed Mortgages

If you sold your home and are carrying the note for the buyer, that interest is special. You can’t just lump it in with your E*TRADE 1099. You have to list the buyer’s name, address, and Social Security number. If you forget that SSN, expect a nasty letter from the IRS and a potential penalty. They use that info to cross-check the buyer’s 1098 mortgage interest deduction. It’s a closed loop.

The OID Headache

Original Issue Discount (OID) is the bane of many taxpayers. If you bought a bond for less than its face value, that "discount" is technically interest that earns over the life of the bond. You might get a 1099-OID. Even if you didn't see a dime of cash flow from it this year, you likely have to report a portion of that OID as interest. It’s "phantom income," and it’s a total pain.

Part II: The Dividend Minefield

Dividends aren't all created equal. You have ordinary dividends and qualified dividends.

Ordinary dividends are what you list on Schedule B. They are taxed at your standard income tax rate—the same as your salary. Qualified dividends, however, get the preferential capital gains treatment.

Wait, so do I list both? Yes. You list the total ordinary dividends on line 5. This includes the qualified ones. Later, on your actual Form 1040, you’ll peel off the qualified portion to calculate the lower tax rate. It feels like double-counting, but it’s just the IRS's way of seeing the "gross" before they let you apply the "discounted" tax rate.

Don't forget about "Nominee Distributions." If you received a 1099-DIV that includes money belonging to your brother because you hold a joint account but he’s the one actually keeping the cash, you have to show the full amount and then subtract the nominee portion. You basically write "Nominee Distribution" underneath the subtotal and subtract it out. It tells the IRS, "Yeah, I saw the 1099, but this isn't my money."

Part III: The Foreign Account "Trap"

This is where the 1040 Schedule B instructions get serious.

Line 7a asks if at any time during the year you had a financial interest in or signature authority over a financial account in a foreign country. This includes bank accounts, securities accounts, and even certain types of insurance policies.

If you say "Yes," you might also have to file FinCEN Form 114, better known as the FBAR.

The threshold for the FBAR is $10,000. If the aggregate value of all your foreign accounts hit $10,000 at any point—even for five minutes—you have a filing requirement. This is separate from your tax return. It goes to the Treasury Department, not the IRS.

Why People Get This Wrong

A lot of expats or dual citizens think, "Oh, I didn't make any money in that account, so I don't need to check the box."

Wrong.

The question isn't about income; it's about existence. If the account exists and it’s over the pond, you check the box. If you have more than $50,000 in foreign assets, you might also need to file Form 8938 under FATCA rules.

The penalties for missing these foreign reporting requirements are draconian. We're talking $10,000 or more for "non-willful" violations. If they think you’re hiding it on purpose? It can be half the balance of the account.

💡 You might also like: Flash of Genius: The Brutal Reality of the Robert Kearns Story

Specifics That Trip Up Even the Pros

Let's talk about Accrued Interest.

Say you bought a bond in the middle of a payment period. You had to pay the seller for the interest they earned up until that date. When the bond eventually pays out, you'll get a 1099 for the full amount. But you shouldn't be taxed on the part you paid to the seller.

In Schedule B, you list the full 1099 amount. Then, on a separate line, you write "Accrued Interest" and subtract the amount you paid. It ensures you only pay tax on the interest you actually earned.

Then there’s the U.S. Savings Bond trick.

If you cashed in Series EE or I bonds to pay for higher education, you might be able to exclude that interest from your income. You’ll need Form 8815 for that. But you still have to show the interest on Schedule B first before you take the exclusion. It’s all about showing your work to the IRS. They hate surprises.

Actionable Steps for Your Filing

Stop guessing and start organizing. Here is how you actually handle this without losing your mind:

- Gather Every 1099: Don't just look for 1099-INT. Look for 1099-DIV, 1099-OID, and 1099-PATR (for cooperatives). Even if you didn't get a physical paper in the mail, check your online portals for "Tax Documents."

- The $10 Rule: Banks aren't required to send a 1099-INT if you made less than $10. However, the law says you still have to report that $9.50 as income. If you're filing Schedule B anyway, add it in.

- Check Your Foreign Balances: Look at the highest balance for every non-U.S. account you own for the entire year. If the total across all of them hit $10,000, mark your calendar for the FBAR deadline (which usually aligns with the April tax deadline but has an automatic extension to October).

- Identify Nominees: If you're holding money for a parent or child in a joint account, determine exactly how much of that interest is yours. Prepare to list the full amount and then "deduct" the nominee portion with a clear label.

- Review Seller-Financed Details: If you sold a property on a contract, find the buyer's SSN now. Don't wait until April 14th to realize you don't have it.

The 1040 Schedule B instructions are effectively a road map for transparency. If you follow the prompts—especially regarding the foreign account questions—you're insulating yourself from the most aggressive audits the IRS conducts. Keep your records for at least three years, though for foreign assets, some experts suggest keeping them indefinitely because the statute of limitations can sometimes stay open longer if "substantial" income is omitted.

👉 See also: Bank of Hope Stock: What Most People Get Wrong About This Niche Giant

Get your totals ready. Double-check the math. And for heaven's sake, don't forget to check the "Yes" or "No" boxes in Part III. Leaving those blank is an invitation for a manual review.